My Best Worst Job: Illegal Catering In A Haunted Basement

Hard work, if you can get it.

It was the summer of 2012, and I was juggling two part-time jobs: one as a freelance marketeer for a local puppet theater, and the other as Membership Coordinator at a local humanist society. These are, in fact, real jobs that exist in the city of Minneapolis, where I live.

I spent all of August making marketing plans for a puppet show about genocide and wrangling septuagenarian atheists. Neither of these jobs paid particularly well, and I was delighted to receive an email midway through the month inviting me to bid on a month-long catering contract with a local art gallery.

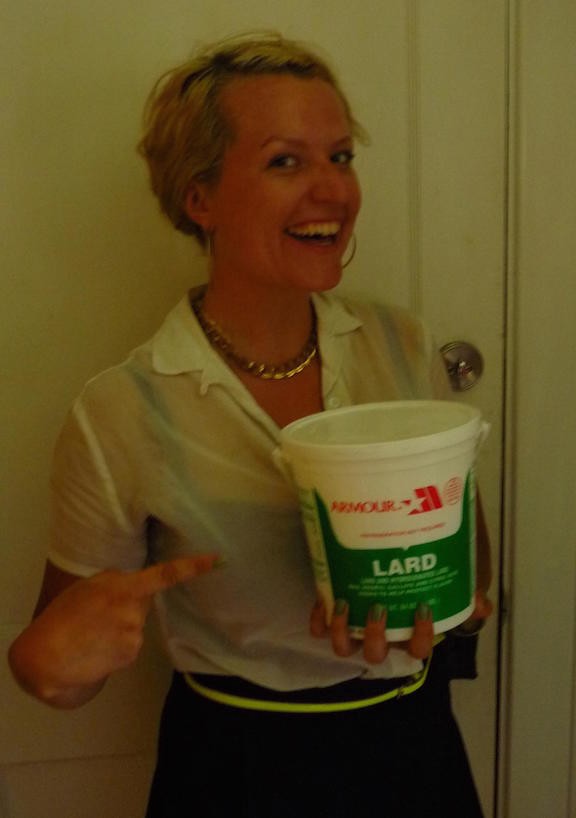

My friend Brie and I had an on-again, off-again sideline as unlicensed caterers to supplement our nonprofit salaries. Most of our gigs were events for friends and family members, the kind of client who doesn’t care much if they find an incidental hair as long as you bring enough cookies. I worried that the gallery might require us to produce proof of a license, which would have put the job far out of reach, financially. The state of Minnesota requires a catering business to have a food establishment license ($384), a licensed food manager on staff ($154 for the exam, $35 application fee), access to a commercial kitchen (ballpark = $160/month), and a vehicle for deliveries with a “cleanable interior” (I suppose this depends on your definition of cleanable).

Brie and I had kept costs low thus far by operating our business illegally, in the catering community’s seedy underbelly. We did all of our prep in Brie’s tiny, shared apartment, and frequently roped our friends in as volunteer prep cooks.

As it turned out, the gallery shared our values of thrift, economy, and lawlessness. They needed a month’s worth of dinners for actors in the gallery’s annual haunted house, called the Haunted Basement, for an initial offer of $2,900. It became clear why they’d called us: no one else would do it. My partner in crime Brie declined the job, citing the literal impossibility that we would turn a profit.

I was not deterred.

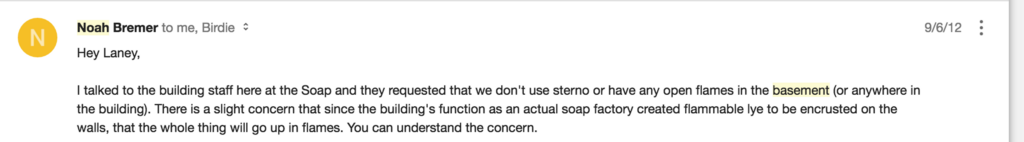

After a bit of back and forth we settled on $4,000 for all the food, $2,000 up front and $2,000 upon completion. They would supply the paper plates, the forks, knives, a chest freezer, and an electric oven. The last was added after I asked about sternos and received the following email:

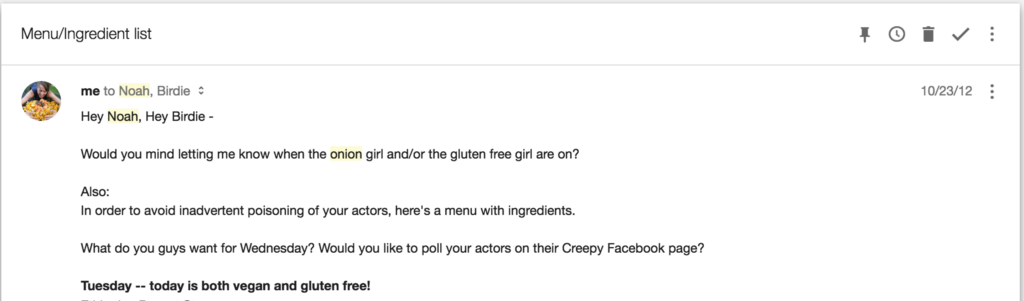

This was an obstacle but not an insurmountable one. I revamped my dinner plans, and purchased two massive electric roaster ovens on sale at Sears. I cleared with my boss the use of the humanist society’s commercial kitchen. My 1991 Dodge Neon had been freshly vacuumed. I was ready. I sent off the first week’s menu: Tamale Pie, Pumpkin Stew, Root Vegetable Curry, Vegetarian Chile Verde, and Savory Bread Pudding.

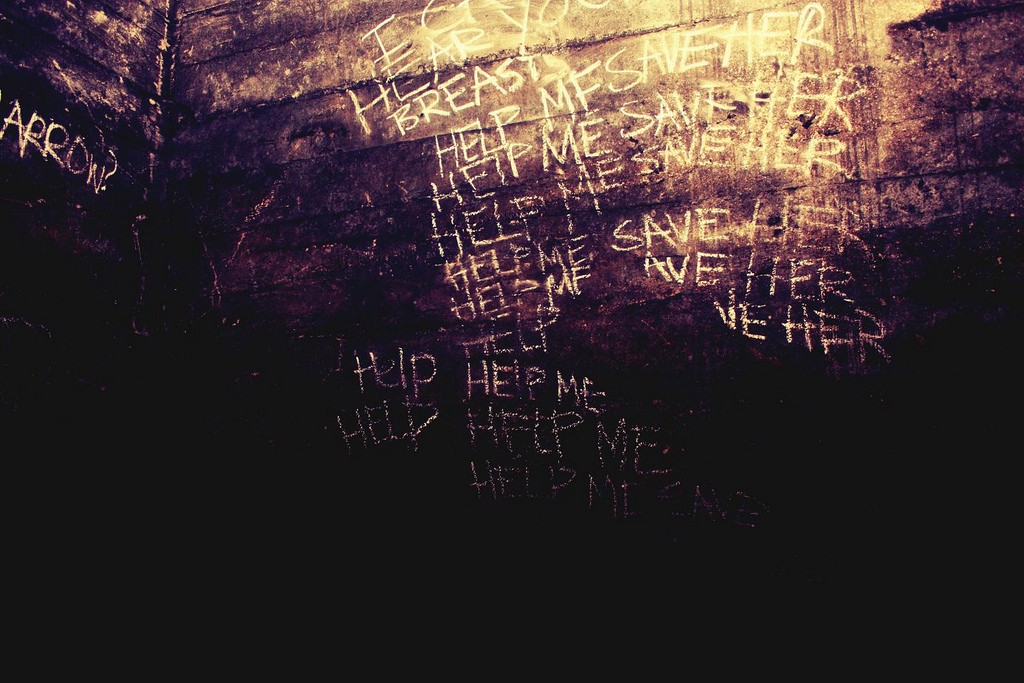

When I’d agreed to the job, I’d heard about the waiver all the guests had to sign, and the chalkboard in the break room that tallied the number of times someone urinated or puked on themselves in fear. My new bosses had failed to mention, however, the specially formulated boutique scents (later written up in the New Yorker).

As I wobbled down the steps to the gallery’s basement on my first night, 20lb roaster oven in hand, I caught the tail end of something I can only describe as not right — a mixture of sweet rolls, hamburger meat, and rotten flowers. The first participant group had just been led into the set, and I could hear them start to scream as I turned into the green room.

I plugged in the first roaster and headed back to the car for the rest. The screams followed me up the stairs, punctuated by the occasional masculine cry of “OH FUCK.”

The nights rolled on, and I got better at maneuvering the stairs in the semi-darkness. The “uncle” count — people who’d tapped out before completing the full tour — grew by about 50 each week, with the occasional puker to spice things up. I started showing up earlier in the evening, so I’d get to see the creeps (as the volunteer actors were called) in the final stages of preparation, gluing crayons and staples to their waxy white faces, putting on their filthy onesies and grotesque masks. They were surprisingly shy, as a group, although they delighted in recounting stories of how they’d made massive men scream like little babies. I got the feeling that these were people who’d often dreamed of making muscular polo-shirted men shriek in fear.

My nurturing instincts began to hum as I regarded the creeps. They’d voluntarily given up multiple fall weekends to be in this damp, asthma-inducing basement. Their motivations were pure: they were creeps for the joy of creeping alone. Only a few of the actors that year were paid, and those few received only a very small stipend. I respected that commitment, although I didn’t exactly share it.

As I grew to love the creeps I tried harder to please them, making three or four grocery runs in a single week, buying brownie mixes in bulk, offering to hand roll noodles for the lasagna I offered them. I tested the limits of communal storage in the fridge and pantry at my temporary kitchen and at home. When I learned that multiple creeps had food allergies, I struggled to find recipes that didn’t involve onions (this still confuses me) or gluten. I asked if they’d like to vote on toppings for baked potato night.

I spent hours on prep, wedging it in around my day jobs of marketing puppet genocide and attempting to convert people to atheism. By the month’s end my forearms were roped with muscle from hauling the roasters. A chunk of my pointer finger was missing from an unfortunate incident with a tomato and a too dull chef’s knife. My Neon smelled like lentils all the time, and I was deep-in-my-bones exhausted.

In retrospect, I can see that the creeps would have been happy with almost anything. At times they would spontaneously applaud when I carted in the first roaster. They were and remain the most appreciative catering customers I’ve ever had. I loved them.

They frequently expressed their gratitude by offering special, extra creepy tours of their basement kingdom. I felt terrible refusing, but I am so easily frightened that the television show Buffy the Vampire Slayer gave me nightmares as a child. I managed to avoid the basement’s interiors until the night of the wrap party.

Like the creeps, I am shy, and that night the director of the show saw me standing awkwardly by the beer table. “Come on,” he said, taking my hand, “I’m going to give you a lights-on tour!” He led me through the different rooms of the basement, each created by a different artist. I remember most clearly the slaughterhouse, walls coated in fake blood, giant faux meat grinder suspended in the corner. This was apparently the source of the not right smell.

The rooms were incredible, even in the light, horrifying and intricate in their detail. The director, Noah, offered editorial as we passed from room to room. “This is where we suggest to people that they take off their Basement issued onesies, so that they complete the tour pantsless. This is where we separate couples into good or bad meats to see if they will wait for each other or keep going. This is where we dance our marathon dances.”

His descriptions of the basement rooms and the characters that populated them made me wish I’d risked public urination and taken a tour myself. I hugged him in thanks and offered to save him a slice of cake with extra frosting, the catering equivalent of a private tour.

This tender moment almost made up for the moment a week later, when I discovered that the stress of that month had caused me to break out in shingles. After making sure I didn’t have an immune disorder, my doctor asked, “Were you working on a political campaign? Usually it’s only extreme exhaustion or stress that can trigger this in a young person.” Embarassed, I shook my head. “No,” I told her, “I’m a caterer.”

Dolores “Laney” Ohmans is a reformed caterer and current foraging apprentice. She lives with her partner, Emily, and two dogs in Minneapolis, MN. You can find her on instagram: @laneyohmans.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments