For Vast Majority of Americans, the Estate Tax Is A Non-Issue — Why Do We Still Care?

The unpopular levy affects only 10,000 very rich families a year

In honor of the centennial of the Estate Tax — or, as it was cleverly renamed a couple decades ago by the Republican opposition, “The Death Tax” — the Washington Post put together some interesting facts and figures about the current state of affairs. The key takeaway is that it affects almost none of us, and most people hate it anyway.

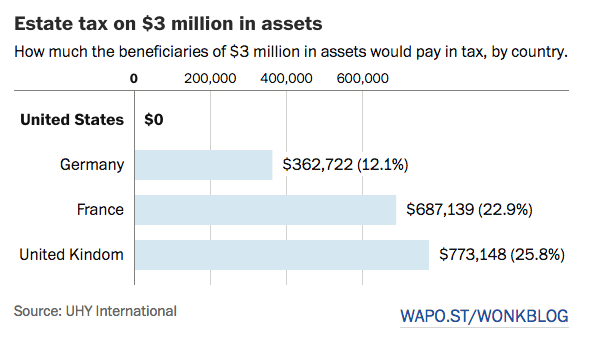

Why America is a smart place for very rich people to die

EU citizens who inherit vast estates, or even not-that-vast estates, comparatively, have a much larger burden than Americans do. And those rare Americans who are tasked with paying taxes on their parents’ massive wealth often squirm out of the responsibility.

As of now, the debate affects few people, and even with current thresholds, wealthy families may find strategies to circumvent the legal tax rates. “There is a whole industry of estate tax lawyers, who help families to avoid the tax legally,” says Roberton Williams, an economist with the Tax Policy Center in Washington.

According to the policy center, only 2 in 1,000 households would be expected to pay the estate tax, raising a fairly small pool of money for the federal government — $20 billion, or less than 1 percent of federal revenue. Officially, beneficiaries would pay the top income tax rate — about 40 percent — on inherited wealth above the taxable threshold.

Look, they made a chart!

Yet even though overwhelming majorities of Americans are entirely untouched by this tax, except to benefit from it in the form of roads and schools and so on, they want it overthrown.

A Gallup poll in March found that 54 percent of respondents sided with Trump’s plan” [to do away with the estate tax]. … “Maybe people think, they might win the lottery someday,” added Williams of the Tax Policy Center.

A Princeton University study suggests that people might not understand the rules and effects of the estate tax to its full extent: Even people who had a critical attitude toward economic inequality — and realized that it is growing — still supported a repeal of the estate tax.

That study also found that “public opinion in this instance was ill informed, insensitive to some of the most important implications of the tax cuts, and largely disconnected from (or misconnected to) a variety of relevant values and material interests.”

So do Americans oppose the Estate Tax because they don’t understand it? Liberals seem to think so. As policy, it affects only just over 10,000 families, total, and “actually aligns neatly with the U.S.’s notion of fairness,” maintains a frustrated Stephen Martin in the Atlantic.

America’s Un-American Resistance to the Estate Tax

If Americans had a better grasp of their own history and traditions, Martin argues, they might have a more sophisticated understanding of why the tax has been and remains such an important and useful tool to combat income inequality and prevent class stratification.

As The Economist has noted, America’s early state governments threw out laws that encouraged the accumulation of wealth over generations, following the example Thomas Jefferson set with the Virginia legislature in 1777. They got rid of the English legal precedents of primogeniture and entail — under which titles and property were inherited in their entirety by the oldest male heir — forcing families to divvy up their wealth among more children. Jefferson cited Adam Smith, who called the idea that people should control their estates well beyond their death “manifestly absurd.” Jefferson insisted that “the earth belongs in usufruct to the living.”

Similarly, Alexis de Tocqueville identified the breaking-up of estates as one of the cornerstones of the young country’s success. “What is most important for democracy is not that great fortunes should not exist,” he wrote, “but that great fortunes should not remain in the same hands. In that way there are rich men, but they do not form a class.”

Unfortunately, I’m not sure a history lecture about de Tocqueville has ever changed a voter’s mind. One can’t Sorkin a person into agreeing with them. The website Tax Notes agrees, acknowledging both that, “from the perspective of the receiver, [the estate tax is] simply an income tax,” and yet it’s a roundly unpopular one. At this point the status quo is fixed; it’s not going to change: “If Americans were fooled into disliking the estate tax, they were fooled pretty thoroughly — and more or less permanently.”

Face It: Americans Just Don’t Like the Estate Tax

It explains:

The estate tax is only a puzzle when we assume that redistribution is the only thing that matters to voters, Sheffrin suggests. In fact, Americans consider other issues when they think about taxing inherited wealth. Sheffrin organizes those issues under the rubric of “folk justice,” which he defines as “the full constellation of attitudes that individuals hold in their daily lives about all dimensions of justice.”

In trying to explain opinions of the estate tax, Sheffrin employs the concept of moral mandates: broad, nonnegotiable conceptions of right and wrong that are largely impervious to logical argument either for or against. One moral mandate in particular seems to have fostered opposition to the estate tax: its association with death, which taps notions of grief and family responsibility. In that sense, the GOP’s famous rebranding of the estate levy as a “death tax” was brilliant.

There’s more sound logic in that piece, too, but the upshot seems to be that the estate tax may be a valid but doomed cause. People who care about economic inequality might be better served by finding other, more effective and palatable ways to get America’s wealth recirculating.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments