Til Colonoscopy Do Us Part

When my husband asked me to marry him, on his knees in the Rubin Museum, I said “Yes, on one condition. Get a colonoscopy. Like, before our wedding.”

We were in the gallery of the Buddha who was similarly uninsured. John, a small business owner and artist, had gone intermittently without health insurance over the years. He coached sport fencing, and his body was regularly nicked. He was okay courting disaster — his first marriage had proved that — but I was not.

Admittedly, requiring he get a colonoscopy wasn’t the sexiest pre-nup I could concoct, but if he was going to tie the knot with me (TIL DEATH, ahem), then he was going to let me know his polyp count, or lack thereof.

His father had a history. John Sr. died in a Texas hospital, mere months before I met John, in his early sixties of “unknown causes.” Apparently it is still possible for medical providers to ignore etiology. Though cancer was not the thing that killed him (“toxic blood” was), John Sr. had been diagnosed with colon cancer in his forties. It was caught early and treated. It did not return. But that kind of cancer is happy to check in with the next generation.

There was more to this verbal contract as we talked about the terms of a life together: John was going to have to maintain enrollment in proper health insurance. Lying beside him at night I could practically hear the cancer cells hatching their strategic plan (though I have no memory now of the conversation in which I learned that bit of family medical history). Was that his sleepy breath or the soft sound of tumors multiplying?

Perhaps he would agree to the procedure if only to assuage my anxiety about his inevitable imminent demise. I watched a lot of opera as a kid, and I knew passion (such as we had) and suffering (such as the Buddha taught annoyingly that we all had) were paired like wine and cheese. In my mind’s eye, he was already wasting away from an illness we could have forecasted and therefore prevented.

But still, the premiums.

We couldn’t realistically afford them, not with his staggering debt from his divorce. This sum was incurred when he finally left, afraid his very young boys would think conflict was just what relationships meant, and hopeful to find a better paradigm. In the divorce decree, he’d agreed to assume all the debt from their shared business, which had tanked like a synchronized swimmer with their marriage. Alas, I would inherit that debt, too. Meanwhile, he had secured an overpriced basement apartment in the ritzy Chelsea neighborhood where his ex had her home to remain as close to his young children as possible.

That was where John lived when I met him. The refrigerator door opened into his front door. (Yes, it was that cramped and poorly designed.) Rent was almost $2K/month. He relied on credit cards for everything, transferring balances, to create normalcy for the boys. They slowly became familiar with arriving on Thursday evenings to find me cooking sausages with mushrooms and kale for them in the single skillet. Each night they spoke on the phone to their mom who probed sharply, “Who is there with you?” Then she reminded them they did not have to eat anything they didn’t like. They could have what they really wanted at their true home — aka hers.

I say a diet of greens, roughage, is best exposed to while young, even if only a bite here or there. Your colon will thank me later, I thought, as we played Connect Four on the floor, already knowing I was in it with all of their colons, and family susceptibility, for the long haul. The nearest grocery store was overpriced, the theme of the neighborhood, but it was convenient. It was also convenient to pray that things would get better. To take the long view (hey, any life has its vicissitudes) at which my husband has always excelled.

Do ugly finances have to lead to ugly health? A mean package deal.

The year he proposed to me and the colonoscopy, John was turning 42 and I, about to be 35, was hoping for a so-called geriatric pregnancy. If he was going to die on me when we were newlyweds and turn our first year into a tragedy that would secure me a heartbreaking-but-bestselling memoir, I wanted to know. I liked knowing. Or at least I thought I did.

“Let’s just plan on me not getting cancer,” he said. “And not getting hit by a bus.”

“Buses don’t aim for people,” I said. “But cancer might.”

My husband is generally in good health. He feels “puny” maybe once each year, as a virus makes its way through him. Industrious, he keeps working, and he doesn’t worry too much about what could befall him if things worsened. He’s willing to gamble his odds on the thousands of dollars he can save if he doesn’t buy health insurance. But during the reign of Obamacare, he wasn’t the sole decider of how he played the odds, because a person had to factor in the cost and consequence of the government penalty. And now he also had to factor in me.

I was raised to see health insurance as second only to God, and we didn’t believe in God. My father was a personal injury and medical malpractice lawyer, so he had seen all the things that can go horribly wrong — and, by observance, so did I. He had also seen all the ways insurance coverage can, quite literally, stand between you and destitution, handicap, loss of life. He had sued the insurance companies over and over, and knew how arbitrary and often dysfunctional their policies were. On their customer to-do list, supporting health was actually last. They wanted money, like everyone else in late capitalism. But when you were sick, or when you were finding out if you were sick, you needed what they had — the power of protection, intervention, investigation.

Despite our pre-nup agreement, John never got the colon cancer screening that first year. We were busy wedding planning, then busy being pregnant and having a baby, then busy securing health insurance for the baby and settling out the cluster of mismanagement of my pregnancy and planned home birth by our then-insurers, Oscar. A name that sounds just like your buddy, right?

We have two kids now, in addition to my stepsons, and they are all on CHIP. I’ve been informed my children’s CHIP eligibility will expire midway through this coming year, for reasons I still can’t unravel. We lost our government subsidy and the increased premiums for 2019 will result in my husband being covered for only one or two months. He will make some medical appointments before his insurance runs out, and then drop it without consequence.

Here we go again.

I have had to step away from the altar of insurance because we cannot make the money appear to pay for it. And there are no penalties now, in this lawless age of Trump, except my wobbly prophecy of catastrophe.

I won’t know what, if anything, lurks in my husband’s bowels. I’ve repainted him as dying a million times. Meanwhile, he flows merrily through his days, accepting his “whatever” fate. Is that the better option, to go through life with faith and acceptance? Or is it denial, transfigured?

Truth is if we find out unfavorable health information from any screening, we’d have to decide what to do with it, and we might not be able to afford options. It is both a spiritual and practical question. And if you know that your financial limitations might suffocate your means of treatment sometimes it’s better not to know anything at all.

Marriage, love, having children — it’s all about risk. You can’t know what will meet you on your path; you can’t know how bodies, people, priorities, may change. What the cells will do. What you will cling to, lose, gamble. Here I am five years later, choosing the premium, wondering if it covers colonoscopies in, say, January or February. The weight of all of this looms. Life is a wager.

But we continue, suffering as the Buddha predicted, doing our best to continue loving each other as the Buddha advised. My husband tries to laugh it off, eats cheese, and enjoys the absence of diagnosis and the presence of our vivacious children. People like me, married to our worst fears, have to figure out another way to rest in the unknowable.

My husband would say “Focus on the good health we have now!” and I’d say that’s short-sighted and we’re just goddamn lucky. But you can live your whole life out seeing only as far as the next month, and being grateful each day that your bowels turn cleanly, and your body carries on.

Still, before our tenth wedding anniversary, I hope we’ll get back on our feet enough that, premiums paid, he can walk into the medical office and have his insides reviewed by a professional. Even if it means I’ll never write that bestselling tragedy memoir.

Sara Nolan writes personal essays and other effluvia; she also teaches the personal essay through Essay Intensive and offers labor birth support to people becoming or re-becoming parents.

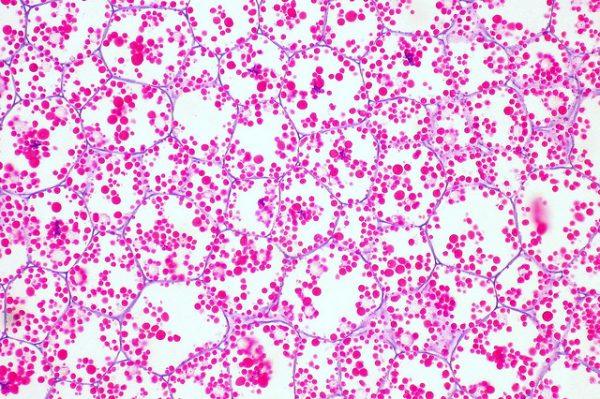

Photo credit: Ed Uthman, CC BY 2.0.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments