Me-Made-May May Not Be Made for Me

Create clothes by hand to save neither money nor time!

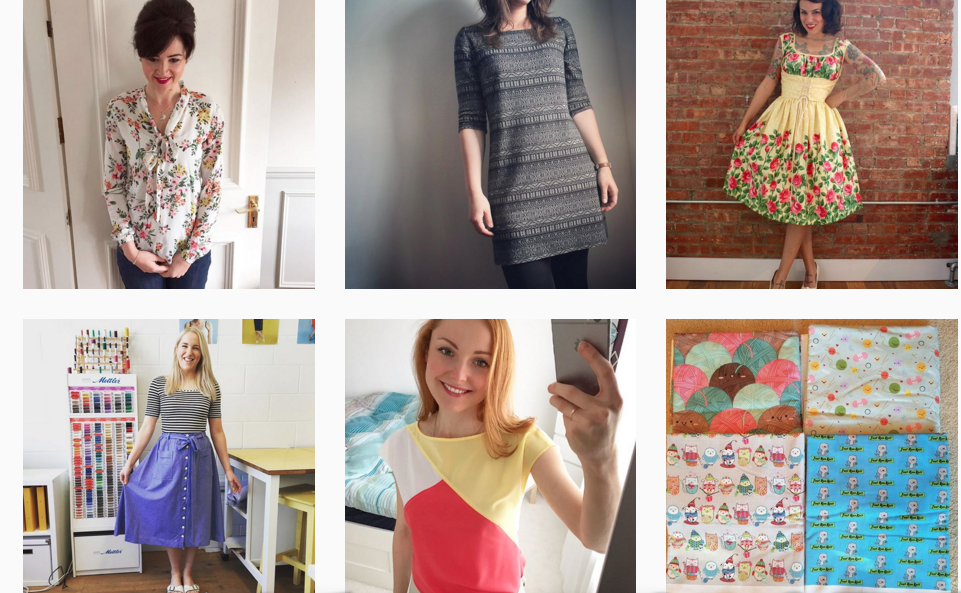

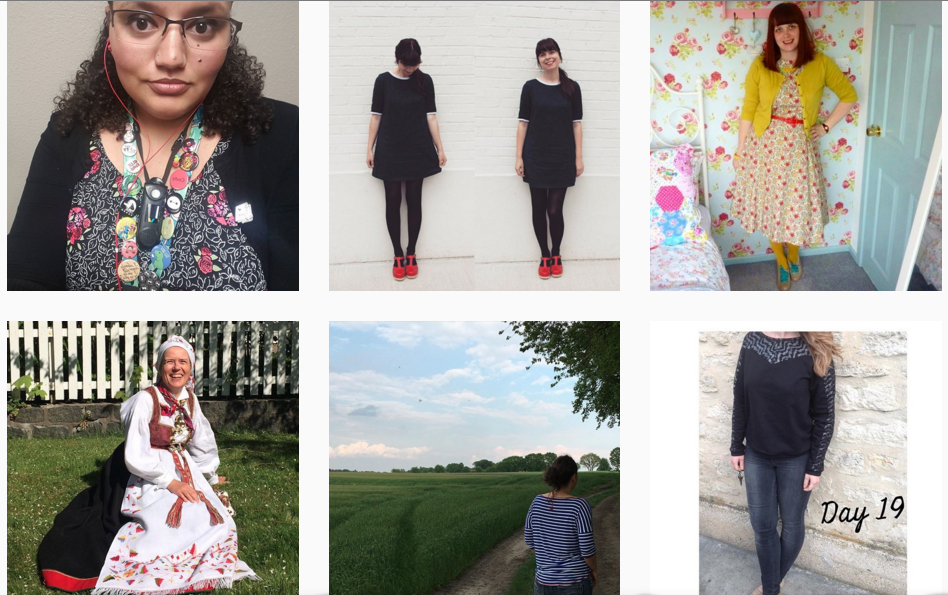

The crafting internet is extra-full of selfies these days, demure smiles and big grins as the knitters and sewists show off their handmade garments, all hashtagged #memademay (or #mmmay16). Me-Made-May is a month of showing off self-sewn clothes. It was started by a woman named Zoe Edwards, who, in 2010, decided to devote the month of May to her own personal challenge to wear only clothing she had made herself.

After Edwards blogged about her challenge, she gained some co-participants. In an interview in Seamwork, she says that the first year 80 people took on the challenge but that last year she counted about 600 people showing off their me-mades on social media. Some pledge to wear only handmade items; others commit to wearing at least one self-made item each day. So the selfies and mirror shots that fill my Instagram and Tumblr are mostly about the clothes.

While I follow all these excellent sewers on Instagram (and look at their blogs when I remember) because I like seeing sewing projects and getting excited about making things myself, Me-Made-May stresses me out. In fact, Instagram during Me-Made-May does the same thing to my brain as wandering through Target or Century 21: it triggers anxiety around overabundance.

I do a lot of sewing, and though I make more quilts than clothes, I have a few self-sewn dresses and and skirts that are in pretty reasonable rotation. But, like most of us who have picked up a copy of The Life Changing Magic of Tidying Up, I have too many clothes; and as I get excited about sewing new ones, I simultaneously panic about adding more things to my closet. A few years ago, sewist/author/lexicographer Erin McKean blogged about 100 of her self-sewn dresses, noting that there were still more that weren’t included in the list. While I know that I’ll only make better clothes with more practice, I don’t want to stuff my closet (which I share with my husband!) full of dresses.

Because I am not primarily a garment sewer, I’m not great at it: I make things that aren’t perfect, and then they don’t get worn very often. But I can’t get rid of them because I’m proud that I’ve made them. Quilts, on the other hand, are perfect and warm and usable even if they’re not perfectly square or the stitching is wonky. They also make great gifts, where a tank top with too-tight armholes and uneven darts does not.

Me-Made-May makes me wish that I was home sewing clothes to wear to work instead of working. It also makes me wish that I had a minimalist uniform of 3 black dresses and one pair of great jeans to wear on the weekend. Full stop.

If I think about Me-Made-May not as a challenge to sew more clothes, but rather as a push actually to wear the things I have already made, a little of the stress fades away. In the Seamwork interview, Zoe Edwards talks about people using Me-Made-May to learn about what they like and don’t like about the clothes they’ve made; about what works and doesn’t; and what is worth making again. It doesn’t have to be only about showing off.

Further, while it’s a bit cutesy, I’m excited about the name “Me-Made-May” because it underscores that the clothes are and can be made by the person wearing them. It’s far better than a smug “handmade” given that all clothes are made by hand, by people sitting at sewing machines whether they’re in Los Angeles or Bangladesh. (Important reminder about the Planet Money T-Shirt Project!)

One thing that Me-Made-May makes clear is that we are living in a golden age of sewing. There are so many cute patterns available by all sorts of indie pattern designers, like Colette Patterns, Deer&Doe , Christine Hayes, Grainline Studio , Sewholic, Blueprints for Sewing, and many others. Most sell patterns as PDFs, so if you want to make something you can start right this very moment. And the sewing social media means you can see how dresses look on different bodies, in different fabrics, and with all sorts of tweaks and modifications.

This is a reflection of how cheap fast fashion has moved home sewing from a frugal choice to leisure-class activity. These indie-designed patterns cost anywhere from $6 (as part of a Seamwork subscription) to $24 for a printed Wiksten Tank pattern. Most are in the middle, hovering around $16 for printed pattern or $12 for a PDF.

Fabric prices rage much more widely, but the nice stuff that seems to make home-sewn clothes worth the effort doesn’t come cheap: an apparel-quality double-gauze (like this one that I’d love to make a top out of) is $12 to $20/yard, and the absolutely perfect Liberty of London Tanya Lawn is $36.52/yard. In December, I bought a printed pattern for an Archer button-down shirt for $18, 2.5 yards of $12/yard chambray for $30, and a spool of matching thread for $4. That’s $52 total, and I haven’t started the project yet, so I don’t actually have a new shirt.

It’s possible to sew for cheaper, pairing library books, free patterns, and self-drafted designs with on-sale and non-name-brand fabrics, but a fast-fashion item will still be less expensive. Old Navy is currently selling this chambray button down for $26 — and you’ll know if it fits before you put in all the sewing time.

Cheap fast fashion has moved home sewing from a frugal choice to leisure-class activity

Earlier this week, Collette Patterns posted about a sale on Adelaide ($5 rather than $9 for a PDF pattern), a dress that had caught my eye some months ago. Weakened by all the Me-Made-May stimuli, I bought the pattern and printed out the pieces. Then I came home on a Thursday night to a pile of clothes in the place in my building’s lobby where people leave things they no longer want. The item on top was a pair of grey Banana Republic pants in my size, so I grabbed the whole pile. I went upstairs and tried everything on: three pairs of pants and two skirts that all fit perfectly, and were all utterly work-appropriate.

I glanced over my shoulder at the neatly stacked pile of Adelaide printouts, put the new clothes in the laundry, and went to bed.

Dory Thrasher has a PhD in Urban Planning and works as a Data Analyst for the New York City Department of Social Services. She makes quilts, reads books, yells about inequality, and runs marathons. She lives in Brooklyn (of course).

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments