What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: Gordon Korman’s ‘No Coins, Please’

You have to get your permits.

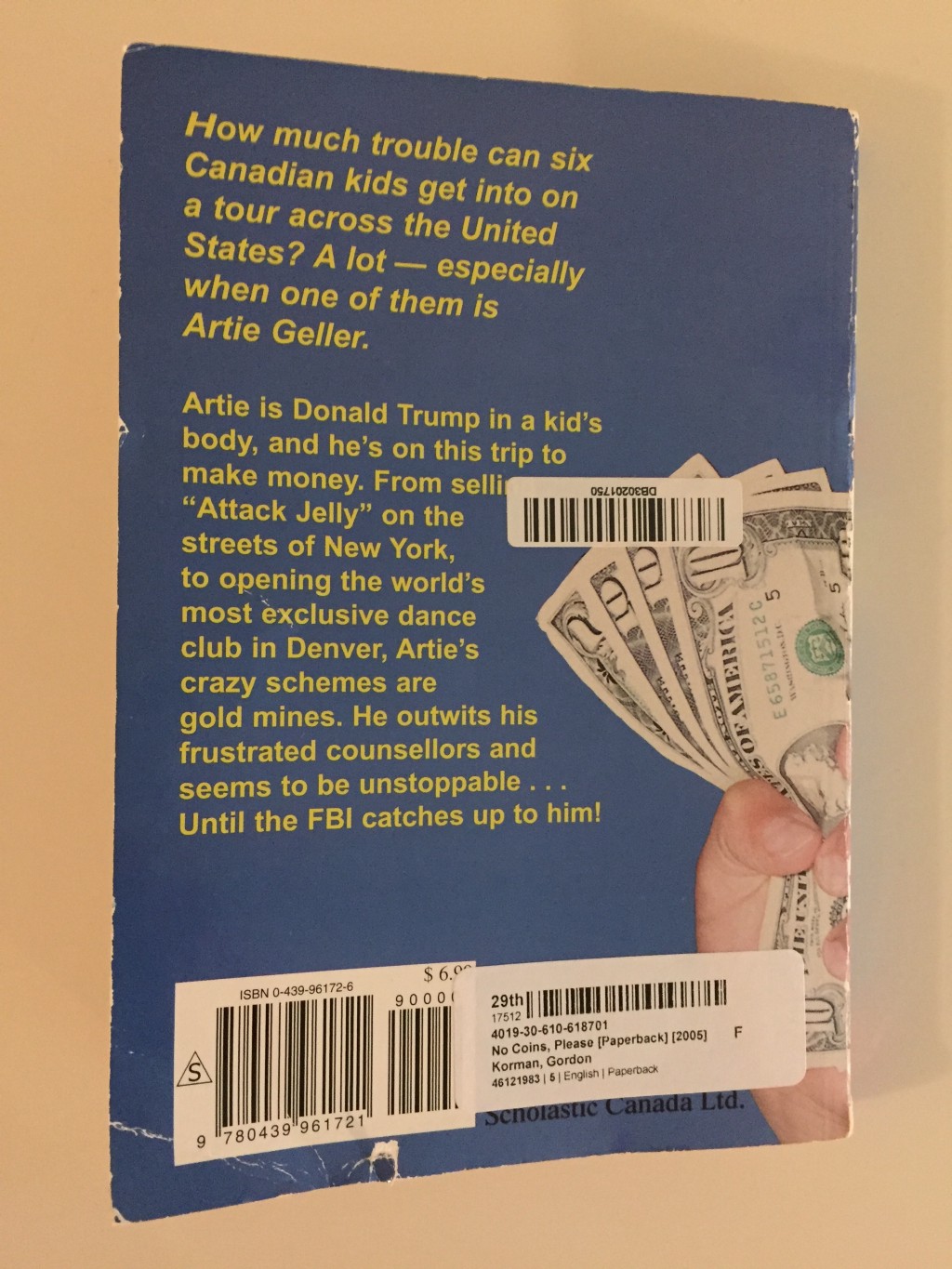

Before we get started, I have to note the copy on the back of the 2005 paperback edition of No Coins, Please:

Artie is Donald Trump in a kid’s body, and he’s on this trip to make money.

The whole point of No Coins, Please is that eleven-year-old Artie Geller is a con man, a perpetual liar who is only in it for himself and who can neither be trusted nor left unsupervised.

In 2005—and I don’t know if this text was also included on the original 1984 edition—someone at Scholastic decided to compare him to Donald Trump.

Also, Artie ends up losing all of his money by the end of the story. But we’ll get to that.

No Coins, Please is the rare middle-grade novel that is written from the perspective of two horny eighteen-year-old Canadian boys (men?) who decide to become Juniortours counselors so that they can tour America and… um… score. (There’s a lot of sex—and homophobia/transphobia—that went way over my head when I read this book as an eleven-year-old.)

Juniortours appears to be the kind of outfit that any sane parent would not let their eighteen-year-old sons join; Dennis and Rob will each receive $1,000 for five weeks’ work ($2,322 in today’s dollars), during which time they will drive six preteen boys across the continental United States. The cost of feeding and caring for six boys, along with the gas and essentials required to drive across the country, is covered by Juniortours—which is to say that Juniortours gives Dennis and Rob a chunk of money at the beginning of the trip and tells them to make it last. (Spoiler alert: it doesn’t.)

Korman could have done an entire story about the cost of getting six boys across the United States, especially from the perspective of two Canadian teenagers. (Everyone in this story seems to accept that two eighteen-year-old boys serving as sole chaperones for six children is normal, so I will too.) In fact, a lot of his story deals with exactly that: speeding tickets, towing fees, the difficulty of feeding six kids on a Juniortours budget.

But then there’s Artie.

Artie, also Canadian, is on Juniortours to see how much money he can bilk out of American rubes.

What’s so delightful about this book is how logical Artie’s whole enterprise is. He begins his trip with $200—the same $200 that Juniortours asked every camper’s family to provide, to cover “souvenirs and incidentals.” In New York City, Artie buys $200 worth of supplies and starts selling Attack Jelly (think Pet Rocks, but with a protective element) at $10 a jar. He knows that what he’s really doing, in this case, is selling the performance—little kid in a tuxedo, giving a fast-paced sales pitch about a jar of jam—and New Yorkers pay street performers.

By Washington, DC, Artie has turned his $200 into thousands of dollars. The DC mindset is all about knowledge, power, and status, so Artie changes his game. He drops $500 at a toy store and builds a multi-path racetrack outside of Capitol Hill, complete with toy cars, toy trains, and a self-propelling toy moose. After he gathers a crowd of government officials, he asks if they’d like to bet on which car will win the race. Of course they would; their wonk brains have already run down the various racing paths and determined which one is the fastest. (Spoiler alert: they’re wrong.)

And so the tour continues, with its two plotlines running simultaneously: Dennis and Rob are trying to get laid and not run up too many speeding tickets, and Artie is trying to make America great again. As Artie earns more money from his schemes, he’s able to invest in larger and larger endeavors: renting a bunch of cows and giving tourists the opportunity to pay $1 a minute to milk them, or turning a pretzel factory into the hottest nightclub in Denver. (I really want to make a joke about how Denver probably didn’t have much competition.)

Then the FBI gets involved.

It’s kind of brilliant. Korman knows he has smart readers—even though I was not smart enough to get the sex jokes when I first read the book—so when he writes the nightclub chapters he takes care to explain that Artie secures his liquor service by going to bars and telling the owners that they can sell booze in his nightclub if they provide all their own alcohol and glassware and supplies (and staff) and give him 20 percent of the take. And, just as the reader is starting to wonder whether Artie is really able to do all of this without anyone else noticing, we learn that the FBI has been watching him the entire time.

So we get a chase scene through the Las Vegas strip (where Artie, disguised as an old man, was previously counting cards) and into the McCarran International Airport, where Artie is finally apprehended right before he is able to escape to Toronto.

Here’s what he’s charged with:

[…] in New York, New York, selling without a license, false advertising, contravention of FDA standards and violation of state sales tax laws; in Washington, D.C, running an illegal gaming house, misuse of public property, inciting to riot and littering; at the Lake McConaughy State Recreation Area, Nebraska, defacing public property, bringing livestock into a state park without a permit, operating a dairy without a proper health inspection, operating a store without a license, operating a commercial enterprise on state property without a permit, selling unpasteurized milk in unsanitary containers, involving minors in an illegal operation and evasion of state taxes; in Denver, Colorado, appropriation of a private building without permission, subsequently causing approximately twenty-eight hundred cases of trespassing, performance of unauthorized alterations on said building, failure to pay electric, water and telephone bills incurred, selling food and liquor without a license, price-fixing, operating a discotheque without a license, violation of local fire marshall’s laws, maintaining a salaried staff without withholding appropriate tax and social security deductions, violation of state advertising laws, littering, disturbing the peace, numerous counts of generally immoral business practices and evasion of state taxes; in Las Vegas, Nevada, gambling underage, leaving the scene of a crime and attempting to flee the country. In addition to all of this there’s total failure to pay federal income tax and responsibility for all damages to the Las Vegas Hotel Gunhold incurred in the events leading up to capture, including the cost of two abdominal X-rays.

This might be one of the greatest paragraphs ever written in a middle-grade book.

The FBI decides that since Artie is eleven years old and they don’t want to get the media involved (ah, those sweet pre-internet days) they won’t press charges. They will, however, insist that Artie pays all of his taxes and license fees, along with all of the associated fines—and after giving the FBI $149,764.04, Artie is left with $202.96. He turned a profit, and he’s pleased with that.

So. What have we learned?

- Tour groups that hire eighteen-year-olds to drive buses across the country probably aren’t going to pay very well.

- Running a business the right way, with taxes and license fees and sanitary milk containers and the whole bit, is expensive. There’s a reason why small businesses fail. There’s a reason why people like Artie cheat.

- The FBI will bend the rules if they like you.

I never exactly wanted to be Artie, when I read this book as a child, but I always kind of admired him. Who wouldn’t want to be the kid who knew how to build an enormous toy racetrack and how to get senators to bet on which car would win?

As an adult, I kind of sympathize with Artie for not knowing that he’s supposed to get a license before selling Attack Jelly or No-Frills Milk—while simultaneously being grossed out at the unsanitary conditions in which he distributes both products—because a lot of people start up side hustles before taking the time to learn about licenses and permits and that they’ll have to pay business tax along with federal and state tax.

But I get, in a way I didn’t as a young reader, that Artie isn’t a good person. He believes neither the truth nor the rules apply to him, which is not a great way to go through life—and his decision to flout the rules ends up eating up all of his profits, in the end.

Surely a kid as smart as Artie could figure out how to run a business, even the kind of business that sold novelty products to gullible consumers, while paying his taxes and filing his permits. If there were a sequel to this book, or a ten-years-later timejump, we’d see Artie running Juniortours: collecting thousands of dollars from parents while paying eighteen-year-old counselors $1,000 for five weeks of work and giving them just enough travel money for their campers to survive on hot dogs and marshmallows.

“If you can’t make it last,” I can hear Artie saying, “you’ll have to pay for the rest out-of-pocket.” Then he’ll walk back to his office and smile.

Previously:

What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: Chris Van Allsburg’s ‘The Polar Express’

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments