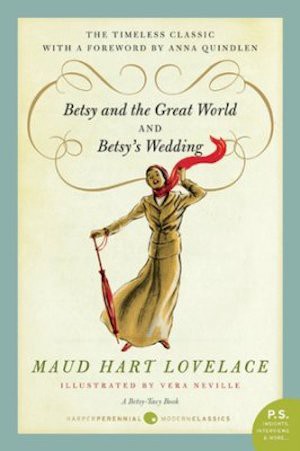

What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: Maud Hart Lovelace’s ‘Betsy’s Wedding’

Cornmeal. Photo credit: Janet Hudson, CC BY 2.0.

I adore the Betsy-Tacy series, so when Billfolder Jennifer suggested Betsy’s Wedding, I was all “yes, please give me a reason to re-read that.” It’s turning out to be a more apropos choice for today than I expected, especially considering how the book ends.

Betsy’s Wedding is the final installment in the ten-book series—which takes Betsy Ray from her fifth birthday to the start of her marriage, which coincides with the start of World War I—and it deals, both pragmatically and intimately, with the finances of setting up a household.

Neither Betsy nor her husband Joe Willard are spendthrifts. They might even be said to pride themselves on their frugality; one of their first decisions, as Joe outlines his plan to propose to Betsy, is to skip the expensive engagement ring and use the money to buy furniture instead.

Also: Joe tells Betsy he’s going to propose before he does it. They talk about what they want that proposal to include and how much it should cost.

These two are doing everything right, financially.

They still run into money trouble after they’re married.

Here’s what Betsy and Joe can’t prepare for:

- Joe quits his newspaper job in Boston to relocate to Minneapolis, where Betsy and her family live. He assumes he’ll get another reporting job right away, because he has a connection at the Minneapolis Tribune, but that connection is no longer working for the newspaper. (If only Joe had paid attention to his LinkedIn emails.) He ends up working for a PR firm at a lower salary than he was anticipating: just $115 a month, or $2,547/month in today’s dollars.

- Betsy finds it much harder to get an affordable apartment than she realizes—even in 1916, she can’t find a place to rent that’s under $30 a month, or just over 26 percent of Joe’s salary—and they only get an apartment because Betsy’s sister’s friend’s mother owns an apartment building and Betsy gets a tip on a newly-available unit. (This is also how apartment hunting works today. Units are rented as soon as they become available, often to the first eligible candidate.)

- Joe’s Aunt Ruth, who raised him, becomes widowed and needs a place to live. She moves to Minneapolis to stay with Joe and Betsy, who have to move out of their apartment and put a down payment on a house in order to have enough room for her. (The chapters detailing Betsy’s quiet resentment at taking on the responsibility of providing for Aunt Ruth are great.)

- Also, the war happens. By the end of the book, Joe is in Officer Training Camp at Fort Snelling, Betsy has rented their home to another family and moved back into her childhood bedroom to save money, and Aunt Ruth has decided to live with a spinster niece in California.

In other words: frugality isn’t enough, and planning isn’t enough. Betsy and Joe eat a lot of cornmeal mush meals, which is apparently the 1916 version of ramen, but then Aunt Ruth shows up and they don’t want to show cornmeal hospitality to a guest. Joe switches to night shift work to earn extra money, but his salary only significantly increases after he sells a story to a major magazine and is offered a job at one of the Minneapolis newspapers that originally turned him down—a job that he has to give up in 1917 when he decides to enlist.

One of the more interesting moments in Betsy’s Wedding comes when Betsy is offered a job at the same PR firm that hired Joe. (Betsy and Joe are both writers, and both published—though Joe hits that “major magazine” achievement first—and one of their shared goals is to make a home that gives them both time to write.) Betsy turns the PR firm down, stating that she has a full-time job keeping house, which is true; the book shows us all of the work involved in cooking three meals a day, sewing curtains, darning socks, and so on. Betsy might earn more money working, but then nobody would be available to take care of the home.

It’s also worth noting that Betsy’s housekeeping work is on top of the work she and Joe have hired a cleaning woman to take care of—paying her $2 a day to scrub floors and manage the most arduous tasks—and that as soon as Betsy moves back into her parents’ home, where her mother does the general housekeeping and Anna (the “hired girl”) does the heavy labor, Betsy immediately goes back and gets that PR job. Does it take two people to keep a household running, in middle-class Minneapolis in 1916–1917? Maybe.

There’s a subplot running through Betsy’s Wedding, and it deals with whether Betsy’s friend Tib, an artist and illustrator who does advertising for a Minneapolis department store, will ever find a husband. Tib says she doesn’t want to get married; she’s happy earning her own money and building her career, plus she’s saving up to buy a car. Here’s how Betsy and Tacy (the best friends that gave the Betsy-Tacy series its title) discuss Tib:

“She isn’t even thinking about getting married!” Betsy cried. “She goes out all the time but she doesn’t give a snap for the men.”

“When girls don’t marry young,” Tacy said profoundly, “they get fussier all the time.”

“That’s right. You know the old saying about a girl going through the forest and throwing away all the straight sticks only to pick up a crooked one in the end.” Betsy looked wise as befitted an old married woman.

“There’s a lot of truth in that.”

“And Tib will soon be earning so much money that she won’t meet many men who earn as much money as she does.”

“That would be bad.”

“And then she’ll start driving around in her car, and getting more and more independent, and she won’t marry at all, maybe! And then what will she do when she’s old?”

Betsy and Tacy looked at each other in alarm.

“She can come and play with my children,” said tender Tacy.

Which is all hilarious, because this is the same stuff they’re saying about unmarried women right now. Men don’t like it when we earn more than they do! If we get too independent, we won’t need men at all! Who will take care of us when we’re old? (Never mind that Aunt Ruth, an older woman who is now dependent on her relatives, was married.)

Anyway, Tib is eventually pursued by a New York millionaire who is attracted to her independent spirit, and after a few chapters of will-they-or-won’t-they, she calls it off because she was only ever attracted to his car.

So yeah, Tib is awesome and I want to know more about her high-earning, car-driving lifestyle—and then the last few chapters are all about Tib meeting some guy (literally some guy, he is barely described and I can’t remember his name) and having a super-fast wedding before all of the boys have to march off to war.

The point is supposed to be that love matters more than money, and that love will conquer all (even the Kaiser), but I always felt disappointed by Tib’s wedding, and more than a little unnerved to see the Betsy-Tacy series end here, with nearly every male character we’ve gotten to know over ten books in uniform. Everyone is at this wedding, celebrating—but as an adult reader, I am aware that many of them won’t survive the war, that all of them will be scarred by it, and that the world itself will change in ways they cannot imagine.

Betsy’s husband will return, because Joe is modeled after Maud Hart Lovelace’s own husband and because Lovelace planned to write one final book, Betsy’s Bettina, about the birth of Betsy’s first child.

So in that sense I know that everything will be okay—and at the end of Betsy’s Wedding, all of the characters seem to think, or hope, or maybe imagine that everything will be okay. It has to be.

But the entire book is about what happens when life doesn’t go as planned.

Previously:

What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: Maxine Rose Schur’s ‘Samantha’s Surprise’

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments