Is Frugality Broken?

Maybe.

I’m still thinking about this article I read yesterday in The Atlantic:

Frugality Isn’t What It Used to Be

It’s a long and kind of dense read, but the point is eventually made:

In other words, individuals’ frugality at the margins — one fewer latte here or there — matters less as the basic costs of living march ever higher.

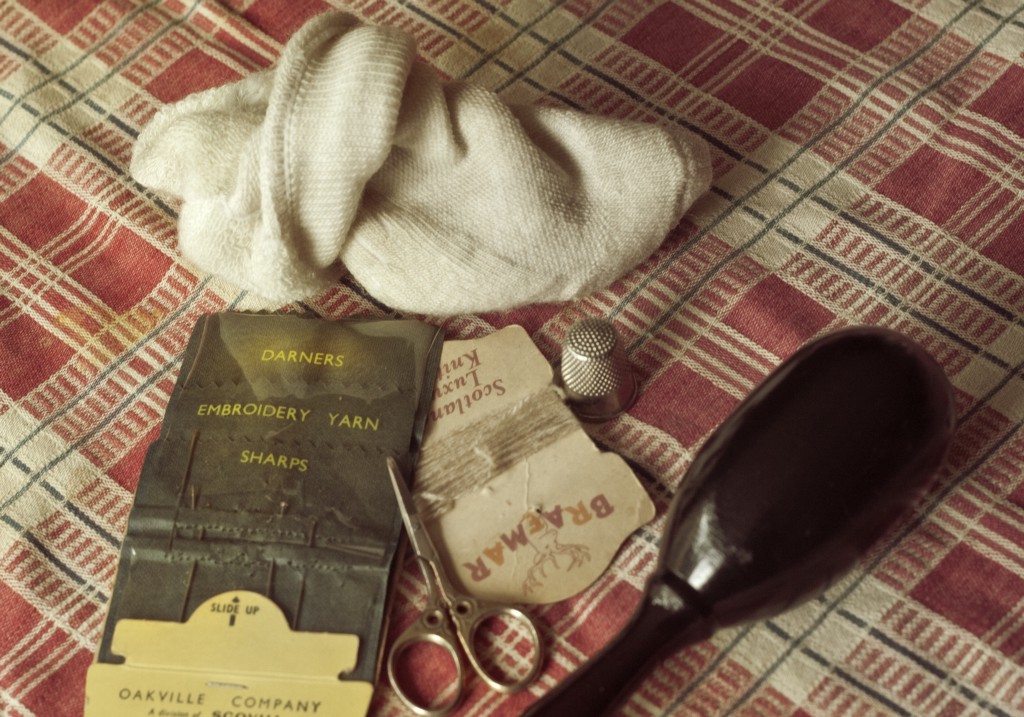

As The Atlantic’s Joe Pinsker explains, frugality makes less sense when it’s just as cost-effective, in terms of both money and time, to replace inexpensive consumer products than to fix them. Not to mention that these products are designed to be tossed out—very few people darn the holes in their cheapo socks because they can just go to Walmart or Amazon and buy six more pairs for $5.

But the article’s secondary point is the more interesting one:

And this gets at why there can actually be a dark side to frugality: Living a pared-down lifestyle necessarily means having a lifestyle to pare down. More often than not, the decision to live frugally is one made by people who can afford to opt out of a well-paid, well-spent lifestyle they have already secured.

Pinsker references multiple frugal gurus, all white men, all formerly (or still currently) in the tech industry, touting the joys of the minimal life:

Mr. Money Mustache had saved up $250,000 by the time he’d been working for five years — no amount of cleaning plastic straws with T-shirt shreds [a frugal technique referenced earlier in the article] would have gotten him there.

To be fair, Mr. Money Mustache practices what he preaches and I’m guessing he doesn’t buy plastic straws in the first place. But Pinsker also references a recent NYT profile of James Altucher:

Why Self-Help Guru James Altucher Only Owns 15 Things

“If I were to die, my kids get this bag,” Mr. Altucher said sardonically as he packed away his laptop, iPad, three sets of chinos, three T-shirts and a Ziploc bag filled with $4,000 worth of $2 bills (“People always remember you if you tip with $2 bills,” he said), and departed a friend’s loft on East 20th Street.

A few months ago, the boyish 48-year-old let the lease expire on his Cold Spring, N.Y., apartment, and dumped or donated virtually everything he owned, more than 40 garbage bags of sheets, dishes, clothes, books, his college diploma, even childhood photo albums. Since then, he’s been bouncing among friends’ apartments and Airbnb rentals.

Which… there’s a lot of judgmental ire I could hurl at those two paragraphs, starting with “and who is taking care of your children so you can bounce from apartment to apartment?” but I’m only seeing the outside of this story, not the inside of it, and I don’t know the details.

The point is that it costs a lot of money to only have fifteen possessions. If you’re James Altucher, it costs $4,000 in small bills; if you’re one of the many people living a different kind of minimalism, it costs check cashing fees, items you can never afford to buy in bulk, the inability to save for the future, and the knowledge that everyone thinks it’s your fault. (When people on low incomes own laptops or smartphones—never mind that these items can be purchased relatively cheaply and are essential for modern life—they’re told that they haven’t been frugal enough.)

So yeah, read the piece, read the Altucher profile, and let us know what you think. Is frugality broken? Does it matter whether you patch the holes in your jeans when you can buy a new pair for under $20? Will any amount of rinsing and reusing Ziploc bags ever save enough money for you to stuff those bags with 2,000 $2 bills, or do you have to earn the money first, and then decide that frugality is worthwhile?

I’ll end this with a personal anecdote: I have spent most of my life trying to err on the side of frugality; even now I don’t own a microwave because I’m all “I can just re-heat stuff on the stove, whatever.” But since I am not low-income—and I wasn’t even low-income when I was earning $20K less than I’m earning now—spending $50 or $100 on a microwave wouldn’t make much of a difference in my budget. Being frugal, in this case, is more about me being lazy; I don’t want to take the time to deal with researching microwaves and figuring out where a microwave would fit in my kitchen and and then having to scrub out the inside every time I reheated tomato soup.

So yeah, even my frugality is based primarily on my other advantages: being able to work from home and cook from home, only having to wash dishes for one person (making that extra saucepan or baking dish required to reheat single-serving leftovers not a big deal), only having to take my preferences into account, and so on.

What about yours?

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments