The Difficulty—and the Inevitability—of Managing Our Parents’ Finances

The Billfold has shared many stories about taking over finances—and, in one case, a bus company—after a parent’s death:

What I Learned About Money After My Parents Died

The first offer that came in [for my parents’ home] was $40,000 beneath the asking price with a $10,000 concession. That meant that after the sale of the house, I would give $10,000 to the buyers, ostensibly for improvements.

I Received An Inheritance. Then I Freaked Out

I played a nonstop game of financial whack-a-mole in the months after my father died. As soon as funeral expenses were paid, estate attorney fees were due. Then it was medical bills and the hefty price of a headstone. Just when we’d taken care of one expense, another would pop up. I was hemorrhaging what my father left on necessities.

Running a Business I Didn’t Want

The first call I received was from my mom, giving me this terrible news. A few hours later I got a second call from a Manhattan number I didn’t recognize: my father’s accountant. He basically wanted to know what the plan was. “Somebody’s gonna need to step up.” I didn’t really understand what he was talking about.

The Wall Street Journal’s William Power has a similar “somebody’s going to need to step up” story, although his is slightly different because in this case the parents are still alive.

The Difficult, Delicate Untangling of Our Parents’ Financial Lives

My wife, Julie, is on the phone with the company where her 82-year-old dad had once worked, trying to change the direct deposit of his pension checks to a bank closer to the assisted-living home where he and his wife now live, which is near us in Pennsylvania. Again and again, she is transferred to the person in charge, “Rose.” And every time, the same recording: “This number has been disconnected.”

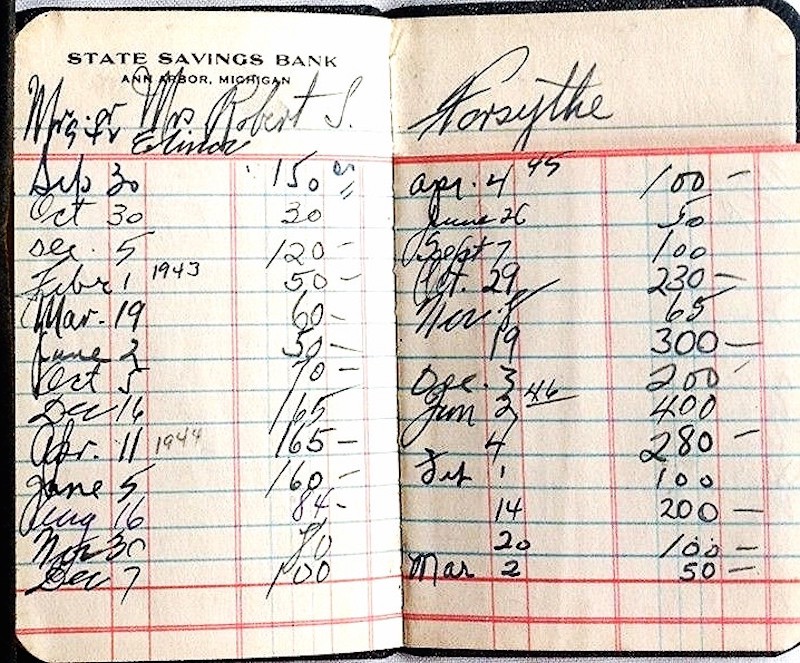

Power and his wife Julie have been trying to sort out Julie’s parents’ finances for the past eighteen months. Julie’s parents are of the generation that still used bank passbooks, balanced checkbooks in pen and ink, and kept important financial information “on notes of scrap paper in various handbags.”

How much work do they have ahead of them? (See “for the past eighteen months,” above.) To start, Power and Julie must complete unique Power of Attorney documentation for many of the banks and brokerages that Julie’s parents used—which Power estimates at “more than two dozen”—because financial institutions often require customized Power of Attorney forms “to protect against dishonest children using POAs to rip off their elders.”

They have to continue to actively manage their parents’ finances, including Medicare benefits, retirement accounts, and an examining of every bank statement to make sure that the utilities, safe deposit boxes, and other recurring services they canceled on their parents’ behalf did in fact stop charging monthly payments. (They don’t always—and yes, you have to get Power of Attorney for something as simple as canceling a Costco membership.)

Lastly, they have to take care of the little stuff:

Consider that Julie’s dad can no longer drive. It seemed simple enough to sell or give away his car. That meant more paperwork, of course, and we knew we had to mail back his New York license plates.

But I hadn’t thought that someone has to find out where to return the E-ZPass transponder, too, and close the account.

It’s an overwhelming amount of work, and as Power well notes, it’s an amount of work that many of us have to prepare to take on someday. He writes that he and his wife plan to make it easier on their own children by keeping a master list of “assets, debits, passwords and sign-ons,” but I can only assume that today’s online password-protected accounts will someday look as antiquated—and be as difficult to navigate—as a stack of bank passbooks.

How are we going to handle our parents’ finances in a world that requires a fingerprint or an optical scan to unlock an account, for example? Or when parents stop keeping organized records because they can just look things up in their Gmail archives? What happens when we move to the thing that comes after Gmail archives, and all of those documents disappear into servers, stored (we assume) but inaccessible?

I wonder if, no matter how hard Power and the rest of us try, we’ll still end up leaving financial messes for our children to clean up—and if, like Power suggests, we should start preparing to clean up our parents’ finances sooner rather than later, while our parents are still physically and mentally able to help.

Not all of us get that option, of course, for all kinds of reasons. But if it’s an option for you: when would you ask your parents to show you how they manage their finances, and when would you know it was time to step up?

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments