When ‘Do What You Love’ Is A Trap But ‘Do What You’re Paid For’ Is Too

In the Times this week, psychologist and author Barry “Paradox Of Choice” Schwartz pointed out that the vast majority of us don’t like our jobs or find them meaningful, and that that’s a huge waste of human potential.

Nine out of 10 workers spend half their waking lives doing things they don’t really want to do in places they don’t particularly want to be. …

Work is structured on the assumption that we do it only because we have to. The call center employee is monitored to ensure that he ends each call quickly. The office worker’s keystrokes are overseen to guarantee productivity.

I think that this cynical and pessimistic approach to work is entirely backward. It is making us dissatisfied with our jobs — and it is also making us worse at them. For our sakes, and for the sakes of those who employ us, things need to change.

In other words, because we work for money and for benefits, it’s assumed that we only work for money and for benefits. If you’ve ever volunteered your time at a shelter or a school or on a political campaign, though, you’ll know that that’s nonsense. Sometimes we work hardest because we’re passionate, not because we’re paid.

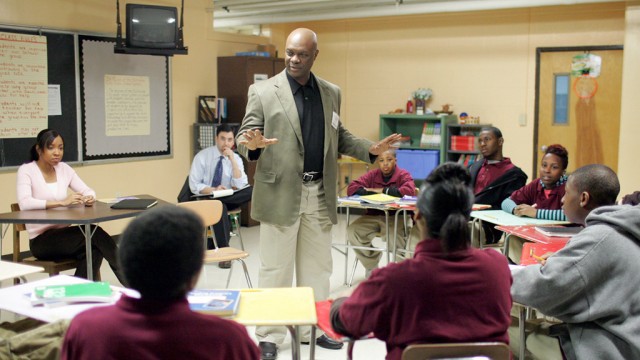

Consider the example of these teachers in Chester, PA: they’re getting screwed by a dysfunctional state government as well as by a destitute public school system which has announced that it cannot make payroll for even the first week of the semester — and yet they have decided to keep doing their jobs anyway.

the 200-member union decided unanimously to work without pay for as long as individual members are able, Paulick said. The Chester Upland School District educates about 3,500 students, with nearly the same number attending area charter schools.

“We arrived at the decision to continue working because we have to put our children first,” she said. “It’s not their fault we’re in this situation.”

These people are heroes, and I hope Obama hears about this and gives them each a medal; but it’s also infuriating that they should be placed in this position, especially coming off a summer: as the union president put it, “’We haven’t had any paychecks coming in over the summer, so it was very difficult to budget,’ for the coming weeks.” Difficult to budget! No kidding.

You could say that, in a sense, the teachers in Chester’s schools have fallen into a trap: because their work is meaningful and important, to the degree that they’re willing to do it without pay, they are being exploited. So argues a new book by Miya Tokumitsu, which expands upon Tokumitsu’s 2014 Jacobin magazine article that went viral. (We wrote about it at the time here.)

The In These Times review summarizes:

DWYL has become a convenient way for corporations to pay fewer people less money for more work. …

Tokumitsu argues that DWYL targets women with particular force. Work that is traditionally gendered female “is often assumed to be done out of love”; it’s women’s supposedly innate nurturing instincts that draw them to nursing, teaching and care work, not a desire for high pay or high status — perhaps one reason why teachers and nurses who strike or protest for better pay are often vilified. But in white-collar offices, too, DWYL culture pressures workers to exhibit joy and gratitude for the privilege of doing their jobs — attitudes that female employees are already especially rewarded for displaying and punished for lacking. In a world of disgracefully inadequate childcare provisions for workers, women often end up in the “flexible” freelance workforce, where the DWYL ethos reigns supreme.

Since I am a woman who had a kid and dropped out of the workforce now two years ago to pursue a “flexible freelance” life of writing and editing, one composed of uncertain hours, even less certain income, and no benefits, except getting to go on TV sometimes, this hits close to home. I have worked for free, although not in some time. I do, at least occasionally, consider the fact that I feel fulfilled and self-directed compensation for the lack of a 401(K). I also realize, again, at least occasionally, that I have let myself be taken advantage of: I neglect to negotiate, to push for better deals, because an undermining voice in my head whispers that I’m fortunate to get anything for work I enjoy.

When other people are getting taken advantage of, though, the situation seems far clearer. How dare we value our teachers so little? And, in a broader sense, what shortsighted idiots we are for ignoring the example of these teachers and others like them, and defaulting to Adam Smith’s assumption that people will only work, or work best, out of fear and duty, rather than out of engagement and love.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments