The Billfold Book Club: Terry Pratchett’s ‘Men At Arms’

Terry Pratchett’s Men At Arms isn’t specifically about money, but money manages to make its importance known in nearly every interaction, starting on the first page when Corporal Carrot writes his parents that his promotion means an extra $5 a month, and on the second page when Carrot writes that he and the other Watch members are pooling their funds to buy Captain Vimes a present, and on the next page when Edward d’Eath becomes “enraged at having to borrow money for this poor funeral,” and so on.

Money is present in these characters’ lives in a way that is often glossed over in other fantasy novels — if you’ve ever read Lev Grossman’s Magicians trilogy, you probably remember the scene where the characters try to figure out exactly how a magical economy works, not to mention who is producing all of these textiles and carriages — and nowhere do we see the reality of money more present than in Captain Sam Vimes of the cheap boots, the man who is resigned to the fact that his pockets will be empty and his feet will be wet while people who can afford a single pair of expensive boots stay dry, the man who is about to marry the richest woman in Ankh-Morpork.

Pratchett describes Vimes’ intended by skewering both wealth and class on the same stick:

When he was a little boy, Sam Vimes had thought that the very rich ate off gold plates and lived in marble houses.

He’d learned something new: the very very rich could afford to be poor. Sybil Ramkin lived in the kind of poverty that was only available to the very rich, a poverty approached from the other side. Women who were merely well-off saved up and bought dresses made of silk edged with lace and pearls, but Lady Ramkin was so rich she could afford to stomp around the place in rubber boots and a tweed skirt that had belonged to her mother. She was so rich she could afford to live on biscuits and cheese sandwiches. She was so rich she lived in three rooms in a thirty-four-roomed mansion; the rest of them were full of very expensive and very old furniture, covered in dust sheets.

We learn later on in the story that Vimes can afford to be poor too, in his own way. His men discover that he pads his boot soles with cardboard while donating his salary to widows and orphans, because the Watch does not give pensions to its deceased members’ spouses and children. If Vimes were truly a poor man, he would not be able to be so generous; it is only his income that allows him to take on the duties he feels the Watch should have fulfilled.

And now to the subject of the Watch, the Guilds, and the various organizations that pack themselves, wall to wall, into Ankh-Morpork. We learn about the Assassins’ Guild, where they only kill if they get paid; the Thieves’ Guild, which earns its income by not thieving (“a modest annual payment and one walks in safety”); and so on. Although the characters wonder aloud how Ankh-Morpork keeps itself running, Pratchett lays it out fairly succinctly: only members of the Thieves’ Guild are allowed to steal, but if you pay the Guild you can be assured of keeping your possessions to yourself; restaurant owners charge as much for ketchup as they do for rats, but have you ever tried to eat a rat without ketchup; when you accidentally get killed after someone invents the gun, Death arrives to collect your spirit and ensure you don’t clog up the streets by haunting them.

The invention of the gun, and the tragedy this causes, forms the bulk of Men At Arms’ plot; the book is much more about power and its abuses than it is about money and its abuses, although the two are joined together the way the Fools’ Guild shares a wall (and a hole) with the Assassins’. It is no coincidence that when the Watch loses their power to keep order, they use rules about wealth and property ownership to form a militia.

But if you still need proof that money and its management is as essential to Ankh-Morpork life as it is to our own (which is, no doubt, what Pratchett had in mind), consider the exchange where Cuddy hears a dirty joke and assumes it is a serious financial statement:

“What? Oh, yes. Of course. It’s nat’ral for a dwarf. Some have got more than others, of course.”

“That’s the case all round,” said Nobby.

“I myself, for example, have saved more than seventy-eight dollars.”

“No! I mean, no. I mean, I don’t mean well-endowed with money. I mean…” Nobby whispered again. Cuddy’s expression didn’t change.

Nobby waggled his eyebrows. “True, is it?”

“How should I know? I don’t know how much money humans generally have.”

What did you think of Men At Arms? Did you recognize bits of our own world in the Discworld?

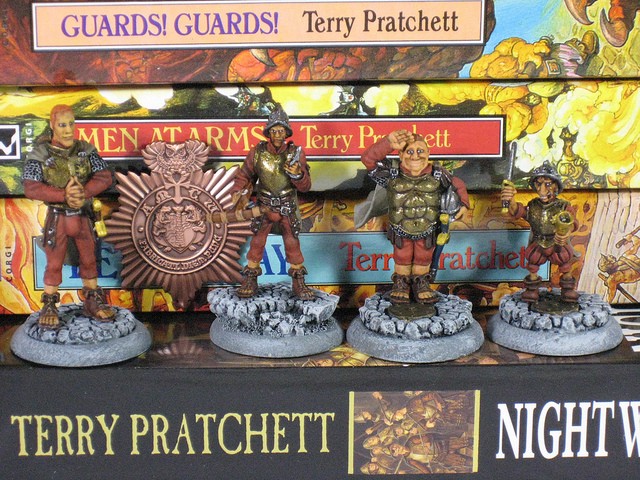

Photo credit: rollingrck

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments