The Tricky Business of Criticizing Big Philanthropy

The objections to wealthy private corporations dedicated to doing good (as they see it) have remained the same since the early twentieth century when the first mega-foundations were created: they intervene in public life but aren’t accountable to the public; they are privately governed but publicly subsidized by being tax exempt; and in a country where money translates into political power, they reinforce the problem of plutocracy — the exercise of power derived from wealth.

Dissent has published a smart primer by Joanne Barkan on “how to effectively criticize big philanthropy.” The piece uses education reform as a way to talk about how unregulated mega-foundations exert influence on policy outside of the democratic process, for better or worse. Barkan talks us through a few common “challenges” you might hear when, say, you have a little too much wine at a dinner party and decide it’s time to be the guy who criticizes billionaires for funneling their money into a “good cause.”

Here’s a good one:

Challenge: You constantly impugn the motives of the mega-foundations. Do you really think Melinda Gates or Eli Broad wants to hurt children?

Response: Of course, the philanthropists aim to do good, but they define “good” for themselves and others. The directors of the Walton Foundation, for example, believe that school vouchers will improve education. By supporting vouchers, they believe, and claim, they are doing good. So it’s not productive to question their motives. But that doesn’t mean that their positions and activity are above reproach. When philanthropists enter the public policy fray, they — like everyone else — legitimately become fair game for criticism and opposition. Tax-exempt status shouldn’t create sacred cows.

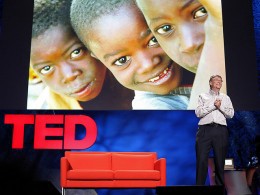

Photo: Steve Jurvetson

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments