Diversity Hiring and the Concept of ‘Fit’

by Aboubacar Ndiaye

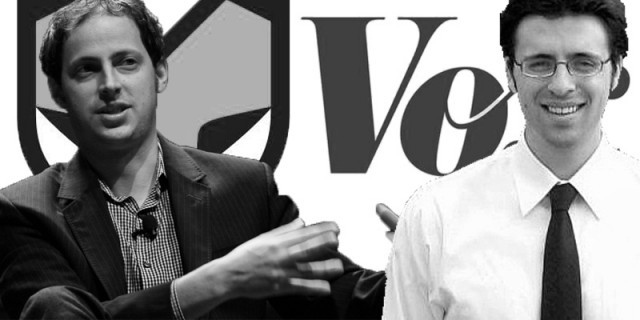

Over the past two weeks, as Nate Silver’s new FiveThirtyEight venture launched, and as Ezra Klein’s Vox.com ramped up its hiring, a conversation about newsroom diversity emerged as it became apparent that the new organizations were going to be dominated by white males. If you’ve been paying attention to this admittedly “inside baseball” discussion, you might have read Emily Bell’s piece in the Guardian decrying what she saw as the regression to whiteness in new media spaces; or Buzzfeed’s Shani O. Hilton’s excellent and realistic guide to trying to built a more inclusive journalistic organization. These articles were countered by an impassioned series of tweets by Melissa Bell, a co-founder at Vox, arguing that the focus on headcounts diminished the very real achievements of the women at these organizations. I have been watching this ongoing conversation with a mix of fascination and excitement. It got me thinking about “Kael Moments.”

Pauline Kael, the late great New Yorker film critic, was quoted, in the aftermath of Richard Nixon’s overwhelming win in 1972, as saying that she did not know how he could have won as she did not know anyone who voted for him. At the time it was taken by conservatives as evidence of the insular world that liberals live in, wholly severed from the hopes and anxieties of “real America.” In the newsroom diversity debate, some of the criticism has centered around this idea: that the reason why these new media ventures have such monochromatic, sausagey mastheads is that they are insulated from the wider culture, and therefore dependent on mostly white, mostly male, and mostly coastal networks for their hiring needs.

The refrain of the discussion, the dog whistle term that has been repeated over and over in interviews with various founders is that these media organizations have been hiring the best talent for the jobs. Nate Silver, in an interview with New York Magazine, called attention to the fact that diversity may be tough to achieve when “85 percent of…applications came in from men.” At First Look Media, an organization bankrolled by Ebay founder Pierre Omidyar, the political news site The Intercept until very recently had three women on its editorial staff (it now has five). At Vox, a website which flirts with gender parity, has so far hired only one person of color, a writing fellow named German Lopez, out of an announced staff of 21 (full disclosure: I also applied for that gig).

Part of the reason for the overrepresentation of white males is the underlying cultural and economic reality at play. The uncomfortable truth remains that white males are still likelier to report so-called hard news, while whites of either gender are likelier to graduate from the marquee journalism programs at Columbia, Northwestern, and Yale. White males also continue to benefit from the amoebous quality of looking the part. They LOOK like a reporter in a sort of a priori, unconscious way. The other part, one that is rarely acknowledged, is the sort of income/class uniformity which plagues both old and new media. It stands to reason that the high costs of the premier schools favored by new media organizations help to weed out potential hires from more disadvantaged backgrounds.

But there’s something else at play here, and that’s the concept of “fit.” Fit is the unquantifiable variable which makes you think that you will be able to gchat stupid gifs with someone, or drink craft brewed beer/fair trade coffee/single terroir wine with them, or bemoan the sorry state of the local sports franchise with them. It is the bro/homegirl quality, the affability borne out of similar backgrounds and similar experiences. It is that feeling of comfort, more than anything, which produces the newsrooms I’ve described, and it is the culture that is the most in need of disruption.

The truth is that we organize our lives around this feeling. We seek spaces that provide the maximum amount of conviviality, from the right kind of city, to the right kind of neighborhood, to the right kind of friends and romantic partners. But when this ethos is transferred into the workplace, it leads not just to a comfortable environment, but to an exclusionary one and a moribund one. When staffing, news organizations should look for discomfort, for ideological discord, for culture clash. They should strive for the sturm und drang which typifies the public discourse. As Ezra Klein stated in an interview, he does not want a workplace where everyone agrees with each other, but a newsroom in which nearly every one is white and where the majority is male and the plurality went to Ivy League schools, the potential for true debate is doubtful. It is begging to have a newsroom in which ideological priors go unchallenged.

Two arguments are usually made at this juncture in diversity discussions. One: that white journalists are able to relate the issues of marginalized, diverse communities as well as any reporter, citing the work of Katherine Boo, Andrea Elliott, and Eli Saslow as examples. Much of this is true (I’m still bugging out over finding out that Sasha Frere-Jones is white), but the lack of lived experience can sometimes be disastrous.

A few months ago, Grantland published a piece (I’m not linking to it) by a young white male writer, Caleb Hannan, chronicling his interactions with a golf equipment designer named Essay Anne Vanderbilt, or Dr. V. for short. After doing some research, he found out that Dr. V. was a trans woman, and informed her that he would include this information in a story that was ostensibly about a golf club. Shortly afterwards, Dr. V. killed herself after begging him not to disclose this information. The story ran and caused an uproar, prompting a self-flagellating mea culpa from that site’s editor-in-chief, Bill Simmons. In the apology, he mentioned that the piece had been read over by a team of editors and a number of lawyers, and not one person pointed out the higher rates of suicide among transgendered persons, not one person told Hannan that outing someone who was passing could have serious ramifications. No one spoke, because no one knew. It exemplified a failure not just of empathy, but of understanding.

The second is the oft-made claim that reporters of color or female reporters are just not easily found. As Hilton said, “there aren’t a ton of amazing, internet-savvy journalists of color just hanging around waiting to be offered a job.” And yet the feat of building a diverse newsroom has been done. Post Bourgie, a blog created by Gene Demby, who is now the lead blogger for NPR’s Codeswitch project, boasts an alumni list that includes Slate Magazine’s Jamelle Bouie, Salon and The Atlantic contributor Stacia Brown, Buzzfeed’s Tracy Clayton, The American Prospect’s Monica Potts (who is white), and many others. Post Bourgie is not alone. The Hairpin is cultivating the next generation of female general interest bloggers. The Toast is publishing stories from new and emerging female, LGBTQ, and POC writers. Colorlines, The Root, The Aerogram, and AngryAsianMan are publishing some of the best cultural analysis on the internet. That is not including the many freelance writers whose pieces pop up here and there, who I’m sure wouldn’t mind having health insurance.

As some people may already know, the Kael quote above is apocryphal. It was misquoted almost immediately after it appeared in the Times that year. What she actually said, and what I find more elucidating, is “I live in a rather special world. I only know one person who voted for Nixon. Where they are I don’t know. They’re outside my ken. But sometimes when I’m in a theater I can feel them.”

The word ken is an interesting choice. It means “knowledge, understanding, or cognizance.” It wasn’t that she couldn’t believe that Nixon had won, or that she wasn’t aware of the existence of his supporters (1 in 3 Manhattan residents voted for him that year.) It was that she didn’t want to “know” them. She didn’t want to cognitively, viscerally interact with the idea that there were people like that out there, and that those people sometimes watched the same movies she did. This process of not-seeing, of willful blindness, is what plagues the new media environment most. That’s not obliviousness, it’s denial.

[Source data, and more charts]

Aboubacar Ndiaye is a writer living in Houston. He has written for the Atlantic, McSweeney’s, and NPR.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments