How the Snickers Bar Changed Over Time

by Carl Hegelman

My relationship with Snickers goes back quite a long way. As a freshman at university in England, I used to stroll every day after lunch with my room-mate up the High to a little kiosk set among the shops a few paces down from the Cornmarket. There was a cheerful, rather saintly old lady in there, pinkly powdered and with an immaculate little wig, her eyes magnified by a pair of Edna Everidge-ish glasses. And from her we would each buy a Marathon bar and stroll back down the High to drink Nescafé in our rooms in college.

That was after I broke off with Toffee Crisp, which I took up with after breaking up with Crunchie bars, which had displaced my first, childish infatuation, the Milky Bar. This was a general progression in sophistication. The Milky Bar was “white chocolate”, which means basically the fatty parts plus sugar. The Crunchie had a golden center of honeycomb sugar. (My chemistry teacher at school showed us how to make this in the lab: melt some sugar, add sodium bicarbonate and — hey presto! — the whole thing would froth up explosively and then cool into a solid honeycombed structure). The Crunchie added the solid parts of real chocolate to the mix of fat and sugar. Toffee Crisp — and I must say I have some regrets about ending this relationship — was essentially Rice Krispie treats with a coat of chocolate, representing a first foray beyond sugar and fat. The Marathon bar took me one step further, into the world of peanuts. Also, the TV advertisements were flavored with a touch of dry, adult humor, usually showing some would-be sportif nerd running tirelessly through the woods under the stimulus of Peanut Power!

And so I was pleased to find, when I arrived on these shores, that they had Marathon bars in the U.S., only they were called Snickers. Silly name, really, conjuring up images of schoolkids telling smutty jokes as they steal a smoke behind the bicycle shed, but who cares? A rose by any other, etc.

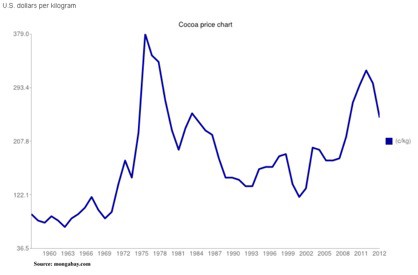

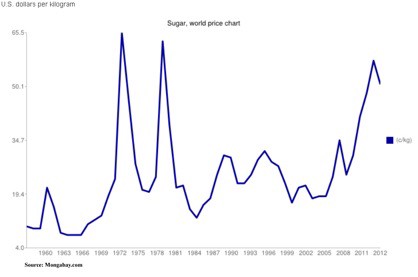

As I became relatively more prosperous in my 40s, I began to buy Snickers by the box. In the 1990s, you could buy a carton of 48 Snickers bars from Smart and Final Iris for about $16, or 33 cents a bar. This was about half the price you’d pay retail. Yet another example of how, in another demonstration of the world’s general injustice, the (relatively) rich can actually buy things cheaper than the poor. Sadly, as time wore on, the price of the box increased about 3% a year until by late last year you’d be paying around $25, or a little over 50 cents a bar. (Or, if you were an idiot, you could pay $37.50 a carton with shipping at Amazon). This probably has something to do with the prices of cocoa and sugar:

There is worse news, still, however, than the inflation. As I discovered around Christmas last year, Smart and Final (they dropped the Iris quite a while ago) no longer sells the box of 48 Snickers bars. They have replaced it with a box of 24 Snickers 2 To Go bars. At $25 the box, or close to $1 per bar. I indignantly refused to buy at what looked like a doubling in price. I thought maybe they were just out of inventory and that when I came back next time the ancien régime would be restored. Alas, not, and so I relented and bought a box of 2 To Go.

Then I found out that the 2 To Go package actually contains two Snickers bars, so the actual number of bars is the same. On the face of it, you still get 48 bars for about $25. Relief!

Short-lived. The 2 To Go bars are not like the old Snickers bars. They are shorter and stouter, being almost square in cross section. So what? Well, strange as it may seem, this actually makes them taste different. Not as good, though it’s hard to describe exactly why. It took me a while, and some math, but I think I’ve figured out why a different shape makes the same ingredients taste different.

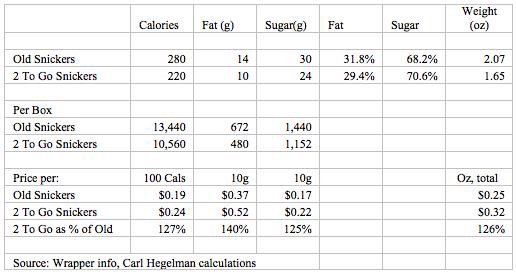

Of course, there may be some rounding errors involved here given that the grams are quoted without decimals but it seems that the ratio of sugar to fat has changed slightly because of the shape, from 68:32 to 71:29 — probably enough to account for the change in taste experience?

A subsidiary bummer, though, is in the cost. The old Snickers weighs 2.07 ounces, the new one 1.65. In cents per ounce, this change in packaging represents a price increase of 26%.

It reminds me of my troubled relationship with ice cream. I happen to like the artificial vanilla kind sold under some generic name (I forget what) at Vons. The cost is around $6 a vat. A few years ago, a vat was five quarts, but then they downsized it to a gallon — an effective 25% increase in price.

While researching the cost of chocolate, I came across another example from back in the old country which also raised considerable ire among my compatriots. Under the guise of changing the shape of its segments (from rectangular to kind of oval, really by cutting off the corners), Cadbury a few months ago slimmed down their Dairy Milk bar from 49g to 45g, effectively raising the unit price by 9%. While the company blames this on commodity and transport costs, truculent Brits have complained that their intelligence is being insulted by the new Yank owners of Cadbury’s (viz., Kraft, Inc.), who are thereby ruining the venerable British brand (established by two Quaker brothers in 1824, by appointment to HM The Queen since 1854).

Back in the U.S., Mars Incorporated, manufacturers of the Snickers bar (and the third largest private company in the U.S., according to Forbes, after Cargill and Brawny), have been much more savvy in pushing through their 26% price increase. The pretext in this case is the company’s public-spirited attitude towards health and obesity. In a 2009 agreement with Partnership for a Healthier America, a non-profit whose Honorary Chairperson is Michelle Obama, Mars undertook to put a 250-calorie cap on its confectionery products. Hence, 2 To Go. Not only that, but they have had to reduce the old Snickers bar from 280 to 250 calories. What are the odds they repriced downwards to keep the price per ounce even?

Relationships are built on trust. I have to tell you, Snickers, the status of our 40-year relationship hangs in the balance.

Carl Hegelman is a nom de guerre. Photo: Phillie Casablanca

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments