Very Wealthy Man Argues that Our Growing Income Inequality Means Our Economy is Working

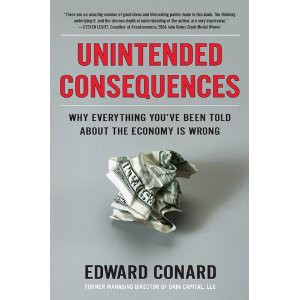

Unlike his former colleagues, Conard wants to have an open conversation about wealth. He has spent the last four years writing a book that he hopes will forever change the way we view the superrich’s role in our society. “Unintended Consequences: Why Everything You’ve Been Told About the Economy Is Wrong,” to be published in hardcover next month by Portfolio, aggressively argues that the enormous and growing income inequality in the United States is not a sign that the system is rigged. On the contrary, Conard writes, it is a sign that our economy is working. And if we had a little more of it, then everyone, particularly the 99 percent, would be better off. This could be the most hated book of the year.

Conard understands that many believe that the U.S. economy currently serves the rich at the expense of everyone else. He contends that this is largely because most Americans don’t know how the economy really works — that the superrich spend only a small portion of their wealth on personal comforts; most of their money is invested in productive businesses that make life better for everyone. “Most citizens are consumers, not investors,” he told me during one of our long, occasionally contentious conversations. “They don’t recognize the benefits to consumers that come from investment.”

Adam Davidson, a reporter for NPR’s Planet Money, interviewed Edward Conard, a former partner at Bain Capital, the private-equity firm he helped build with Mitt Romney, about his new book which basically argues that America’s growing income inequality is actually a good thing. Davidson is right: I hate this book already. But I will probably read it (from the library!), because it’s necessary to know the other side’s argument, before you form your own.

Also infuriating:

Conard’s version of the financial crisis ignores much reporting and analysis — including work I’ve done with NPR’s “Planet Money” team — that shows that some of the nation’s largest banks actively manipulated customers and regulators and, sometimes, their own stockholders to profit from dangerous risk. And for many economists, rising inequality can create exactly the wrong outcomes for society over all. Rather than simply serving as an invitation for everybody to engage in potentially beneficial risk-taking, inequality can allow those with wealth to crush new ideas.

I kept raising these questions with Conard, but he repeatedly waved them off. “I don’t want to talk about rent-seeking,” he told me. “When you go off to a third-world country, there’s a dictator who says, ‘I’m giving the telephone franchise to my brother-in-law.’ It’s pretty hard to do that here.” I countered that many economists see rent-seeking in the United States as a much more subtle but still destructive process. If some rich people are able to get and stay rich by messing around with the rules, then those art-history majors will feel as if they have no chance to break into a well-connected, well-protected elite.

If you’re going to argue that income inequality is a good thing, you better have some solid answers prepared when a reporter raises tough questions to you.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments