Shirley Jackson, Breadwinner

The stress of being a writer, a housewife, and the primary earner for the family in the 1950s

In “The Third Baby’s the Easiest,” Shirley Jackson relays a funny but frustrating anecdote about checking into the hospital to deliver her third child, Sarah. “Occupation?” the hospital clerk asks. “Writer,” Jackson says. “Housewife,” the clerk offers. “Writer,” Jackson says. “I’ll just put down housewife,” the clerk responds.

After reading Ruth Franklin’s highly anticipated biography, Shirley Jackson: A Rather Haunted Life, it becomes painfully obvious that Jackson wasn’t just a writer, either — she was a successful one. In the 1950s, when women were expected to be confined to the domestic sphere, Shirley Jackson, mother of four, was the breadwinner of her family. Her writing brought her definitive financial success, much more so than her husband’s work.

When Jackson and Stanley Edgar Hyman were first married, they squeaked by on his $25 a week salary at The New Republic, and then $35 a week at The New Yorker. The couple recycled used coffee grounds and subsisted on oranges “so they wouldn’t get scurvy,” Jackson remembered. Finally, at the tail end of 1942, The New Yorker’s fiction editor Gus Lobrano accepted two of Jackson’s stories for publication, “After You, My Dear Alphonse,” and “Afternoon in Linen,” for a total of $252, “the equivalent of nearly two months of Hyman’s salary,” Franklin writes. Jackson was well on her way to out-earning her husband.

But even though Jackson was one of the most published female writers of the time, she was still being paid half as much as her male counterparts. “In 1942, for ‘The Man Who Was Very Homesick for New York,’ a story of around 1500 words, Cheever, one of the magazine’s regular contributors, earned $365, or 24 cents per word,” Franklin writes. “For ‘Whistler’s Grandmother,’ a slightly shorter story published three years later, Jackson got $185 — only 13 cents per word.”

Even though Jackson was one of the most published female writers of the time, she was still being paid half as much as her male counterparts.

“The Lottery” changed everything. Lobrano purchased the story for $675, “about three times what he paid for any of Jackson’s previous stories.” In a stroke of particularly “evil luck,” Franklin writes, Hyman’s first book, The Armed Vision, and Jackson’s “The Lottery” were published at the same time. The Armed Vision sold only 1,500 copies and was taken out of print.

According to Franklin, Jackson earned back her advance for The Lottery and began to earn royalties before it was even published. Thanks to the story’s earning power, Jackson and Hyman were able to pay off all their debts and had enough money left over to purchase a small TV.

Jackson finally fixed her teeth, a source of much pain and discomfort over the years. When the family moved to Connecticut in 1950, it was Jackson who purchased the house.

Jackson’s success allowed her to shop for a new agent. In 1951, Bernice Baumgarten came to represent her. “Like Jackson, Baumgarten was the primary breadwinner for much of her marriage, supporting her husband through a dozen less-than-lucrative novels,” Franklin writes. Jackson’s ambition was to be paid adequately for her work — referring to publisher Robert Giroux, she asked Baumgarten, “What is the biggest advance that yacht-owning pirate ever gave to any writer in his life? Because I want to top it by fifty cents.” The two women formed a dream team. When Baumgarten retired in 1956, Jackson praised her toughness: “I don’t think Bernice has ever taken anyone out to lunch in her life and she has certainly never said two words to me about anything but business.”

Perhaps because he recognized Jackson’s talent, or because he knew her work could earn them more money than his writing, Hyman put enormous pressure on Jackson to be at work, constantly. He admonished her for doing anything else, even writing letters. He purchased a dishwasher in the hopes that it would allow her more time to write. But by 1953, when Jackson’s memoir of her children, Life Among the Savages, became a New York Times best-seller, selling around 500 copies a day, Hyman retained little ability to exert control. “When I am making three hundred dollars a day just sitting around he can’t open his mouth whatever I do,” Jackson wrote.

Hyman and Jackson’s marriage had been troubled from the start. Hyman was frank with Jackson in the beginning of their relationship that he did not believe in monogamy. He had extra-marital affairs when traveling, and, later, with former students. And, despite the fact that Jackson out-earned him for years, Hyman was the one who kept a death-grip on the family’s finances. Their income disparity makes it difficult for the modern reader to understand this arrangement. By 1956, when Hyman’s income for the year was $9,900, Jackson’s was well over $14,000. “Later, at a crisis in their relationship,” Franklin writes, “Shirley would accuse Stanley of sabotaging her literary work by forcing her to write magazine stories for money.”

As time went on, despite her rising literary success, Jackson’s anxiety got the better of her, and she wouldn’t leave the house for months at a time. In letters she acknowledged the pressure from Hyman to keep writing and earning, telling her mother that her psychiatrist had suggested her “jitters” were due to overwork. Her usually unsympathetic mother pointed out that not only was Shirley at the typewriter all day, she was also the primary caregiver for four small children and doing the housekeeping.

After the film rights to Jackson’s 1959 novel The Haunting of Hill House were sold for $67,500, money was no longer a problem. Hyman and Jackson paid off their mortgage and outstanding debts. They remodeled the house and opened their first savings account. “I just deposited twenty-four thousand bucks in the bank and am feeling a bit lightheaded,” Jackson wrote.

Jackson also took pride in driving everywhere. It provided a brief respite from Hyman, who could not drive. She bought a series of Morris Minor convertibles, “black with red leather seats, which she called, ‘the pride and joy of my life.’” Her daughter Sarah remembers her always with “one red arm and one white arm, because the car was so small she had to have her arm out, winter or summer.”

By then, Jackson seemed to have lost patience with her husband’s infidelities and controlling tendencies. When she was invited to give a series of lectures, she barred Hyman from accompanying her: “It is now one of the only places where I feel I have a personality and a pride of my own, and I cannot see that go, too, under your mockery.”

Perhaps the financial success would have given the power to leave. But whatever her plans, she never got the chance. In August 1965, she went upstairs to take a nap and never woke up. She was 48.

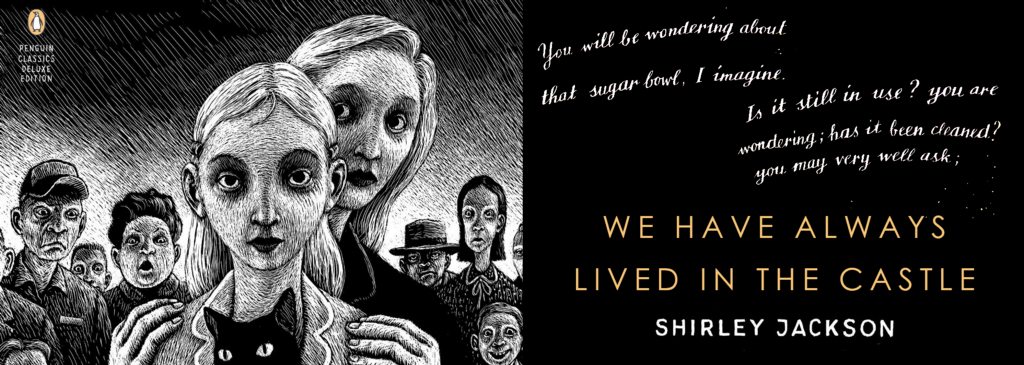

Though Hyman, who died in 1970, dedicated his five remaining years to securing Jackson’s legacy, his efforts were plagued by juicy stories about her practicing witchcraft. In the early days of her career, those rumors were meant primarily as publicity. Hyman liked to tell people that Jackson had sent her black magic to the ski slopes to break his publisher’s leg. And they persist, in a way: just a few days ago, when the cast for the new film adaptation for We Have Always Lived in the Castle was announced, The Guardian called Jackson “America’s queen of weird.”

Maybe it was, or even is, too difficult for people to imagine that a woman could be talented, prolific, and successful without the aid of some kind of supernatural power. But Jackson’s triumphs had nothing to do with signing her name in the devil’s black book.

In the same story about giving birth, Jackson quotes from Othello’s explanation of how he wooed Desdemona: “She loved me for the dangers I had pass’d / And I loved her that she did pity them.” “The line that follows, which she does not quote,” Franklin writes, “resonates silently: ‘This is the only witchcraft I have used.’”

Jessica Ferri is a writer based in Brooklyn, New York.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments