What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: Beverly Cleary’s ‘Ellen Tebbits’

As regular Billfolders might remember, this whole series kinda took off after I wrote a post in honor of Beverly Cleary’s 100th birthday:

‘Scrimping and Pinching to Make Ends Meet’: Celebrating the Way Beverly Cleary Wrote About Money

It’s time to look at Cleary again—not at her Ramona universe, but at another pair of young people growing up in Portland: Ellen Tebbits and Otis Spofford.

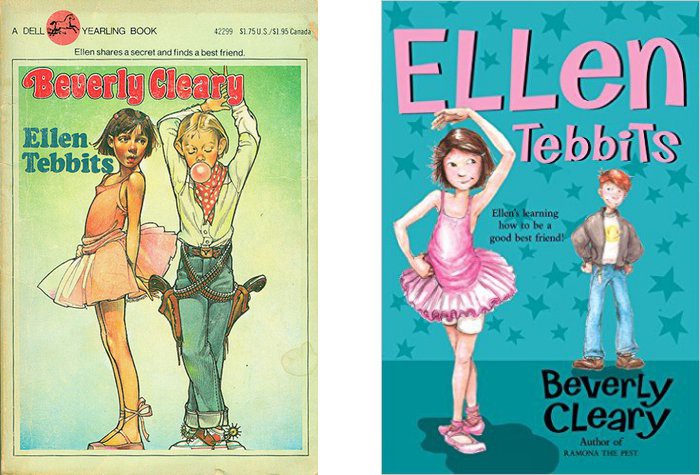

Ellen and Otis each get a book named after them, so we’ll look at Ellen’s story this week and Otis’s story next week—although, as you can guess by the covers, they both feature significantly in each other’s lives. (Another writer would have written an epilogue explaining that they married each other. Cleary, thankfully, does not.)

Ellen Tebbits is very securely middle-class. Because of this, the bulk of Ellen’s story involves her coming to an understanding of who she is compared to her peers—both in terms of personal identity and in terms of privileges.

Ellen does not, at first, see herself as privileged. (Even by the end of the story, she doesn’t use that word, first because she’s a third-grader and second because this book was written in 1951.) She believes she has it worse off than her peers because her mother makes her wear woolen underwear—which, incidentally, children’s literature of a certain era spends a lot of time on the issue of uncomfortable underwear, so that must have been a huge deal.

But Ellen, whose mother can afford to be a little old-fashioned because their income doesn’t require them to take modern shortcuts (we’ll get to that in Otis Spofford), makes her daughter wear woolen underwear in the winter. For all we know, Mrs. Tebbits might have made that underwear herself; the Tebbits are financially secure but are still prudently frugal, and we learn that Mrs. Tebbits is a talented seamstress in part so she can make her daughter’s clothes.

Then Ellen meets Austine Allen, the new girl from California who is also forced to wear woolen underwear. (I’m assuming Austine’s parents think Portland is so cold and wet.) The two of them immediately agree to become best friends, in the Anne Shirley-and-Diana Barry sense, and then start figuring out what that friendship means.

At first, the differences in their relative income and family life are exciting. The Allen family is not presented as financially struggling, but it’s clear that they have less money, and in some ways less time, than the Tebbits family. Austine is impressed that the Tebbits house has an attic, where they can keep old things that have sentimental value or might be useful someday. The Allens, when they lived in California, didn’t have space to store old things, so they sent them to Goodwill. (Their Portland home does include an attic, so that might change in the future.)

Ellen, meanwhile, is impressed that Austine is allowed to cook. Mrs. Tebbits manages all of the household work herself, which means that Ellen’s house is cleaner than Austine’s, but it also means that she doesn’t know how to crack an egg.

Mrs. Tebbits manages the household to the point that Ellen’s teacher does not ask Ellen to clap erasers (a classroom chore that Ellen desperately wants to do) because “cleaning erasers is such dirty work and you always keep your dresses so clean.” Ellen, meanwhile, mentally describes Austine as “untidy,” but she doesn’t put together the amount of time it takes to keep clothing neat and pressed, probably because she doesn’t do the labor herself. In Austine’s family, tearing a skirt means grabbing a safety pin, not a needle and thread.

Then we get the chapter where Ellen and Austine want matching dresses, and the differences in their households can no longer be ignored. Mrs. Allen and Mrs. Tebbits buy the same fabric and the same pattern, but Mrs. Tebbits has both the time and the skill to make Ellen a dress, and Mrs. Allen does not.

Ellen stared. Austine’s dress did not look the least bit like hers. The material was the same, but everything else was different. Austine’s skirt sagged at the botom. The sleeves did not puff the way Ellen’s did and the collar did not quite meet under Austine’s chin. The buttons were sewed on over snaps instead of buttoning through real buttonholes. The waist was too tight and gapped between the buttons. Worst of all, there was no sash to tie in a nice fat bow.

These mismatched dresses lead to Ellen and Austine’s first big fight, and Austine deciding that Ellen is no longer her friend. Although the actual fight derives from Ellen mistakenly believing that Austine untied her sash (it was Otis untying Ellen’s sash, not Austine, although Austine did untie it the first time), the emotion behind the fight has more to do with both girls feeling embarrassed about their disparate lifestyles.

Two chapters later—almost half the book—Ellen is finally able to get Austine to talk to her, though she has to untie and accidentally tear off Austine’s sash to do it. (This book spends several paragraphs fussing over sashes, although to be fair they are hard to keep tidy. When my mom made my dresses, she added buttons to keep the sash in place so I wouldn’t spend the whole day worrying about whether it was coming untied.)

They talk about how they both felt badly that their dresses were different, and both of them apologize for messing with the other person’s clothing. Then Austine fixes her torn sash with Scotch tape, invites Ellen to come over and bake brownies, and they’re best friends again.

Ellen Tebbits is an interesting story, especially in comparison to some of the other stories we’ve been discussing in this series, because Ellen’s family’s financial stability is never presented as a negative thing. She’s not spoiled, like Daphne in Anastasia at Your Service; she’s not the girl who had everything in the world but love, like Maggy in Meet the Austins. She doesn’t have distant parents, like Harriet in Harriet the Spy, and she’s not so rich that she is immediately set apart from everyone else, like Sara in A Little Princess.

Ellen is just financially secure, in a city where a lot of her peers are not, and although she has to check her privilege, the story never suggests that Ellen’s life is worse off because of her family finances—nor does it suggest that having money has made her a bad person.

Next week, we’ll look at Otis Spofford, who lives in an apartment and eats chili out of a can because that’s all his mom has time to cook. Otis is in nearly every chapter of Ellen’s story—he makes fun of Ellen when she and Austine take ballet lessons, he unties Ellen’s sash, and so on—but we don’t really get to see his perspective on life and money until he gets an entire book of his own.

Previously:

What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: E.B. White’s ‘Charlotte’s Web’

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments