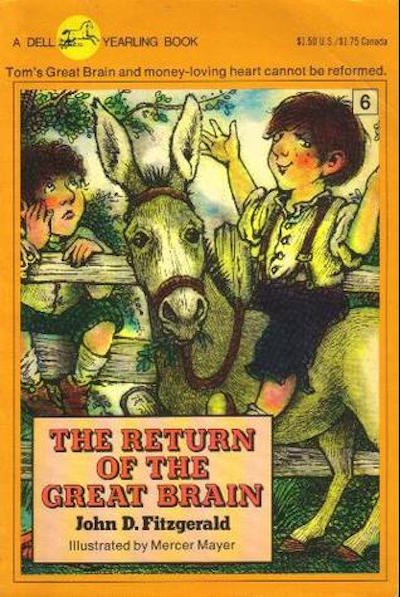

What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: ‘The Return of the Great Brain’

What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: John D. Fitzgerald’s ‘The Return of the Great Brain’

The house always wins.

The most important question in The Return of the Great Brain—the one that still haunts me, years after first reading this book—is this:

After you won a prize at the Great Brain’s Wheel of Fortune, would you walk away? Or would you gamble your prize right back until you’d lost everything?

Tom Fitzgerald—who was a real person, in addition to being the subject of eight Great Brain books written by his younger brother John—is not a likable character. He’s fascinating, and the Great Brain books are page-turners simply because you want to see what this preteen con-man is going to do next, but he’s also a real jerk. He’s the original Dirtbag Encyclopedia Brown, the kind of kid who will get the town sheriff to promise him all of the reward money before revealing that he knows exactly who the murderer is.

Murder—like, in cold blood—is one of the plot threads that weaves its way through this book, along with a group of kids almost getting themselves killed while playing Outlaw and Posse on a nearby cliff (the Great Brain, with his knowledge of physics and knots, saves another child from falling to his death). Life in rural Adenville, Utah in the early twentieth century is not especially safe, although the book, as many children’s books do, makes all of this feel exciting instead of dangerous.

But for me, the most exciting chapter was always the one about the Wheel of Fortune.

Here’s how the Great Brain’s wheel works:

- He tells his parents that he wants to create an honest Wheel of Fortune, not like the rigged one they saw at a nearby carnival. Somebody will win a prize on every spin, and the prize will be worth more than the nickel it costs to play. The adult Fitzgeralds agree to this plan, and allow Tom to create his wheel.

- Tom builds a Wheel of Fortune where every spin does in fact yield a winner. He also sets out an array of prizes that he purchased at the local mercantile: a baseball, a harmonica, a bone-handled jackknife, and so on.

- When it’s time for the first group of kids to play the wheel, and the first kid wins a prize, Tom announces that he can’t actually give the kid the knife he won.

“The prize for number nine is the bone-handled jackknife,” Tom said. “Now, you fellows understand that I only carry one of each prize so you can see what you win. So instead of giving Danny the knife, I’m going to give him twenty-five cents in cash so he can buy a knife just like it at the Z.C.M.I. store.”

And that’s how Tom’s Wheel of Fortune turns into a gambling casino. He earns a profit on every spin, regardless of whether his winner walks down to the Z.C.M.I. store—and only one kid does—or whether the winner gambles that money right back into the wheel.

So I always wondered: would I have been able to walk away? I’d like to think yes. I’ve never been a gambler. The thought of losing money is worse than the thought of winning it, even if there’s a winner on every spin.

There’s one more point I want to bring up, and it has to do with the Fitzgerald family’s relative wealth compared to the other families in Adenville.

Mr. Fitzgerald is the editor and publisher of the local newspaper, which somehow earns him enough money to comfortably provide for himself, his wife, their three sons, their adopted son, and the older woman they take in when her husband dies and she can no longer support herself. The Fitzgeralds—minus their dirtbag son Tom—are good people, and they use the money they have to help those less fortunate, including making a $500 donation ($12,000 in today’s dollars) to help build a middle school in Adenville.

Prior to the new Adenville middle school, the Great Brain had been enrolled in a boarding school in Salt Lake City. He was able to skip grades and attend the Academy early because he was so smart, but he was also able to attend because his family had money—which in turn made his brain even greater, and helped him learn even more ways to con money out of his friends. (Read The Great Brain at the Academy for more on how Tom’s expensive education changed his life.)

There is no doubt that the Salt Lake City Academy is better than the one-room middle school they build in Adenville, and the Fitzgeralds say as much in the story. But Mr. Fitzgerald wanted to build a middle school so the children of Adenville could get more than a sixth-grade education, and so it’s important to him that his sons attend as well. They still have to leave Adenville to go to high school, and at that point the Fitzgeralds’ money can ensure they get the best possible education. (The oldest Fitzgerald son is already enrolled in a high school in Boylestown, Pennsylvania.)

In some ways the Fitzgerald family is like Tom’s Wheel of Fortune: they’re the ones with the money and the power, so they can play the game to ensure the house always wins. They can offer their home to people who need it, and they can help build a rural school—but that’s because they already have a large house and plenty of money and are already planning to send their children to better high schools.

It’s the other Adenville kids, the ones who haven’t ever attended the Academy and only have a few nickels to their name, who have to decide: do I walk away with this twenty-five cent prize, or do I keep playing?

What would you have done?

Previously:

What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: Sydney Taylor’s ‘All-of-a-Kind Family’

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments