The Work of Sex Work

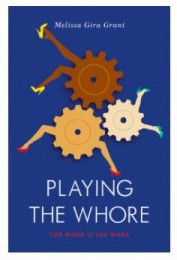

I am in the middle of reading Melissa Gira Grant’s new book, out from Verso next Tuesday, called Playing the Whore. It is very smart, very illuminating, and in many ways, very challenging. I’m planning to interview her for the site in the next week or so, but in the meantime The Nation published a great excerpt today, complete with anecdotes about the workaday reality for jobs we tend to have a lot of preconceived notions about.

Like, say, working in a dungeon! Which as Melissa points out, is not as marginal or as transgressive as it sounds (“There is no one held in chains but those who pay to be placed in them, and even then, only for an agreed time”):

In a dungeon a client can expect that several workers will be available on each shift, and some of these workers will want to do what he wants to and some won’t. A receptionist will take his call, or answer his e-mail and assign him to a worker based on what he’d like, the worker’s preferences and mutual availability. Some dungeons might post their workers’ specialties on a website. They might also keep them listed in a binder next to the phone, the workers each taking turns playing receptionist, matching clients to workers over their shift. After each appointment the worker would write up a short memo and file it for future reference should the client call again, so that others would know more about him. The dungeon is informal only to the extent that the labor producing value inside its walls isn’t regarded as real work. There are shift meetings, schedules and a commission split based on seniority. Utility bills arrive, and are paid. Property taxes, too. In some cases the manager would give discreet employment references. And sometimes people were fired.

There was one group of people who did perform unwaged work in the dungeon: the many male “houseboys” who would telephone, at least once each day, to ask to come and clean. The women who worked in the dungeon knew that managing these men’s slave fantasies was itself a form of work, but when they could just turn them loose on the dishes, the worst they would have to do is check later to see if anything untoward had happened to a glass or fork. It was never meant as a commentary on the years of feminists’ arguing over the value of housework, but it still could feel deeply gratifying that the houseboys were made to understand their only reward would be the empty sink.

This — the notes, the bills, the dishes — is the look inside a dungeon you’ll get when you work there, not when you’re paying for it.

You should go read the rest, then let me know if you have any questions for her that you want me to ask.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments