Stock Options As Explained by An English Major, Pt. 2

Part Two of a three-part series wherein I, an English Major, explain incentive stock options and how they work for employees at startups. Part One is here.

Earning the right to earn the right.

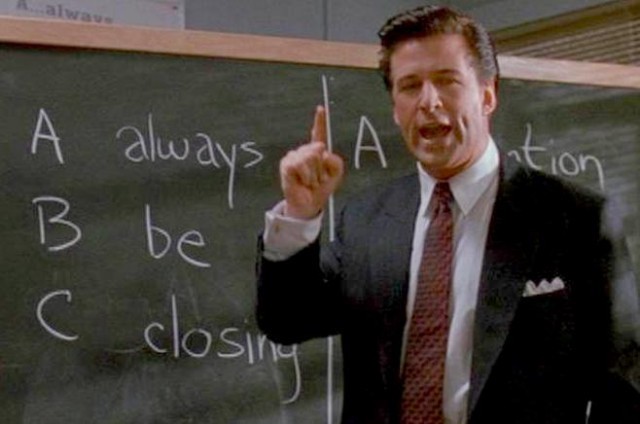

Last week we talked about what it means to be offered stock options in your company, and the difference between what you’ll pay for them and what they might be “worth” (in both the market sense and the tax implication sense). But the thing is, you don’t get all of the stock at once. That’s another reason why they’re called incentive stock options.

Typically, you are set on a four-year vesting schedule. When you “vest” things they becomes yours (kinda). When you vest stock options, you have earned the right to pay for them. This is derived from the olden days, when people put on vests to buy things. Just kidding. Who knows.

Typically (and this varies, so read your contract) your stock options fully vest over four years, but they come a little at a time. After one full year, 25% of your options have vested. That doesn’t mean you get them, it just means you’re eligible to buy them. And then after your first year, the other 75% come in monthly chunks. You vest a little more each month. It can be a reason (“incentive”) to stick around.

To make matters more complicated, and marginally more profitable, after two years it’s common practice to offer employees even more options, vesting on a monthly basis. This is called a retention grant. Because they want to retain you! How sweet. This option grant, though, is usually much smaller.

Now, when you vest you certainly don’t have to buy your stock options, you just can. As long as you’re employed by the company, you have 10 years to buy them (typically). You can put this off however long you like — most people do — or of course not do it at all. They call buying your stock options “exercising,” which I find hilarious and euphemistic. “Bob thinks I should exercise sooner rather than later.” “I’m not sure whether or not I want to exercise.” “I…am fat.”

Deciding whether or not to exercise your options as you vest them — that is, buy them while you still work at the company — requires all kind of tax implication jiujitsu and is not for the faint of heart. Send it to an accountant. You don’t know an accountant? Yeah, I didn’t either and found the notion hilarious. But it’s really, in this case, worth looking into. Ask your more together friends, or your less together, more freelancing friends. Or your friends whose parents are accountants (bingo).

Just get over yourself and ask a few people if they know someone, or know someone who knows someone. Keep in mind that accountants aren’t to be feared, they are just like us except they chose a more practical major in college. They have a very specialized knowledge and/or have fancy tax software. They can be wrong, and they can be wrong for you. Feel free to shop around, ideally finding someone who knows a seed round from his A-round, and follow your gut. If you don’t like the way your accountant does or doesn’t explain things to you, if he or she is condescending or clueless, it’s worth it to walk away.

In case you still aren’t taking me seriously, here’s a threat: if shares in your company are worth much more (in the FMV way, see pt. 1) than what you will have to pay for them, you could owe tens of thousands of dollars to the IRS. Hell, you could owe hundreds of thousands of dollars! You can Google this (it’s called AMT and it’s a whole different post (that I will never write)) and download the forms and try to figure it out, but this is not something you want to fuck with or fuck up. Unless you really, really love the government I guess?

The first time I exercised, I got very lucky, and my boss, stapling my paperwork together, said something like, “You might get hit with something called AMT, you might not. I’m not sure. But definitely have someone look into it, ok?” Luckier still, I was exercising right before the company got a much bigger valuation, so the difference between what I paid for the shares and what, in the eyes of the IRS, they were ‘worth’ was not that much. That difference is, roughly, how whether and what you owe for AMT is determined. In my case, the company I worked for was new enough when I exercised that, while I did trigger AMT, I only owed a few hundred dollars.

Send your option grant to an accountant once you find one, and they will help you calculate this ahead of time. It’s what they are paid to do (and oh, you will pay them).

But there’s more to deciding whether to exercise than tax implications. Sometimes you don’t know enough about where the company is going so you might be justifiably hesitant to exercise as you vest. Sometimes your strike price is pretty high, or your option grant is really big, and it costs a lot of money to exercise. Money you might not have! Maybe you threw your option grant in the bottom of that drawer and forgot about it, and you didn’t know you had to actually pay for these things because you didn’t read this article.

In an ideal, your-shit-is-together world, you sit down and talk to a few people about this.

Friends with money.

First, talk to the finance guy at your company, if there is one. Depending on how your organization is structured (if it is at all, dear lord), this could be the founder, or the President, or the company’s lawyer, or the COO, or the VP of $$$.

TIP: It’s usually the cynical older guy who is excited to put his daytrading past behind him and wear shorts to work every day.

These people are often hilarious and insightful, and it’s good to get to know them. They know that money is fake until it’s real, and it’s to your advantage to know what the hell is going on with it, or else you can get screwed. I always had a lot of embarrassing questions for these people, and they were always really helpful. And unlike my gynecologist, they didn’t laugh at me when I tried to display my often-incorrect knowledge of their field of study based on what I’d googled the night before.

An important thing to ask the money person that you might not be told otherwise: the current FMV of each share (or, the FMV of the entire company and then how many shares there are in total, and then do the math). By now FMV is an acronym you are totally comfortable using, and can say without flinching or throwing up air quotes, so this shouldn’t be a problem. If you ask point blank, he or she might try to be coy, but it’s super shady if they don’t tell you, so they will.

An exact exchange I had (well, roughly recalled):

“So, do we have a fair market value? Are you allowed to tell me that?”

“I can tell you if you ask me directly.”

“What??”

“Just ask me directly.”

“Umm, okay. What is our fair market value?”

And then he told me!

Remind yourself that if the COO was in your position, she or he would definitely demand an answer.

This thought has helped me get over my own hang-ups, time and again: if I were some Wall Street-type of person, or a less insecure person overall, I wouldn’t feel weird about any of this. I’d be like, “Gimme that money!” (or something).

After all, it’s important to know what happens when you give them this money and you own your tiny, tiny (TINY!) bit of the organization. Maybe you’re sure your company will succeed (though you never can be), but what would that mean for you financially? Do they have plans for the company they haven’t shared yet? Do they want to stay private or go public, pursue new ways of making money or keep growing the company, hire more people, renovate the office, fly to the moon? Ideally, you know all this already because you work somewhere that prioritizes transparency and communication, and makes it a point to articulate the goals and practical realities of the company to the people that work for them (LOL). If not, shift in your chair a little and look at your hands if you need to, but then ask.

If you need motivation, try talking to your coworkers about it at happy hour, or on gchat. I know you have happy hour because your company is like a family and you want to spend all your time together and it’s not even like a job, it’s your life, et cetera. Oh, capitalism.

In my own conspiratory gchats with co-workers none of us ever came to any real conclusions, but we did motivate each other to schedule meetings with the relevant party. “Well if he’s doing it…,” tends to be a great motivator.

You don’t have to ask your work friends how many options they got or what their strike price is (though you can always offer your numbers first), but asking them whether they think they’ll exercise when they vest or if they know of a good accountant, is a reasonable discussion. They’ll probably have a million questions, too, and be happy you brought it up first. People don’t often talk about this stuff, but they should.

Just remember that after all that recon you should talk to that mythical accountant of yours before you make any moves. Send them your paperwork and have them double-check everything and give you the go-ahead. You’ll get an invoice from them in the mail a few weeks later that will make you wish you were never born.

TIP: If you ever have the opportunity, marry an accountant. Better yet, become one.

It’s so hard to say goodbye.

If you do quit your job to become an accountant, or quit your job for any number of reasons (there will, no doubt, be many), all of this internal debate about the risks and rewards of exercising sooner vs. later becomes null and void.

Because, surprise! You now have 90 days to exercise your options. If you don’t exercise your options within 90 days of your end date, it’s like they never existed. (Typically! Again, check your contract.)

This can be tough for the same old reasons — you might not have the money, you might not know what you’re buying into, you might owe a lot of money in taxes — but this time, there’s a deadline.

I’ve done this a few times now, but the second time I knew what I was getting into. The first time I suddenly needed to cough up three thousand dollars — money I did not have, thanks to my spending all of it on cabs home from work and Amy’s microwavable burritos.

If you’re lucky, you saved some money at this goofy internet job of yours. Less lucky and maybe your mom has good credit, like mine did, so she can take out a small loan on her mortgage and lend you the money to exercise.

This fact of this still embarrasses me, but it may be the last time I ever have to ask my mother for money, at least for awhile. Then again, you never know.

NEXT WEEK: selling your shares, plus more feelings

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments