Should You Play The Lottery?

by Matt Levine

Did you win the Powerball on Saturday? You did? Hey, congratulations, that’s super, can I see your ticket? Can I hold it for a second? Thanks!

The rest of you might wish you had listened to the Wall Street Journal on Friday:

The Powerball jackpot is up to $600 million, with a day still to go before tomorrow’s drawing. Which means it’s time once again to ask the question: Is this the rare time where it makes economic sense to buy a lottery ticket?

Spoiler alert: No. No it is not.

Every time there’s a big lottery jackpot you get articles like this to do the dreary math for you. The “expected value” of a $2 ticket is less than $2: the jackpot amount that you’d actually get, multiplied by the probability of winning, is a little under a dollar. (The Journal thinks it’s around $0.85; I get more like $0.98.) A dollar is less than two dollars, so it doesn’t “make economic sense” to buy a ticket.

These articles are always wrong. Or, at least, they make no economic sense. Economics attempts to answer the question: “Is it a good idea for me to do this thing, or would it be better for me not to do this thing?” That is a hard question so a lot of people like to pretend it is equivalent to the much easier question “will I have more money if I do this thing, or will I have less money?” But it isn’t, or at least, it isn’t always. If you buy a sandwich, you will have less money than you do now. Economic reasoning is not about getting more money until you have all the money. Sometimes there are sandwiches.

To decide if you should play the lottery you need to compare the (tiny) chance of winning a giant amount of money, on the one hand, with a dollar, on the other. The simple way to do this is to assume that a one in a million chance of winning a million dollars is “worth” the same as a dollar. But, why?

Among other problems, that assumes that a dollar will do the same amount of good for everyone. It is easy to see that this is wrong. If you give me $5,000, it will in fact make me very happy. If you give Logan $5,000, it will make her much happier. If you give Bill Gates $5,000, it won’t do much for him, probably. He makes that much every 6 seconds. He’s not having a party every 6 seconds.

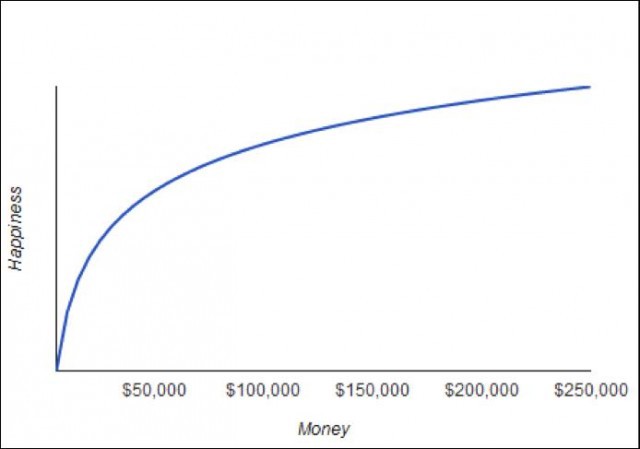

The more money you have, usually, the less good another dollar will do you: the less “utility” that extra dollar has. One way to express this is to assume that doubling the amount of money someone has always does her the same amount of good, however much money she started with. So $5,000 is “worth” twice as much to someone who started with $5,000 as it is to someone who already had $10,000. Something like this:

Fig. 1

This, as this Slate article from the last big lottery jackpot points out, is a good argument against playing the lottery: because $600 million (or whatever) is worth less than 600 million times as much as $1, spending $1 on a bet to win $600 million is a bad idea.

But that’s still just a rough assumption. If you double the amount of money Logan has, she’ll be happy and all, but I gather she’ll still be in debt and she probably won’t even quit her second job. If you double the amount of money Bill Gates has, that’ll be great, he can cure more malaria and so forth, but his life won’t change much either. But if you double the amount of money I have, big things happen. I can pay off my mortgage! I can take a year off to travel! My day-to-day life actually changes in a way that neither Logan’s nor Bill’s would.

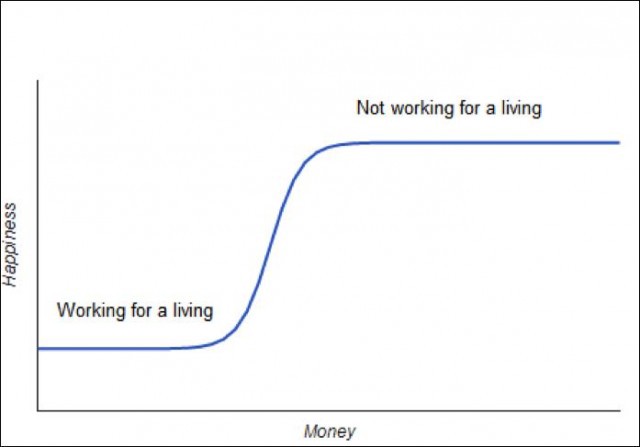

If you win a $600 million Powerball jackpot, even if you have to split it and pay taxes and whatever and only end up with, I don’t know, $70 million, one very important thing happens: you don’t have to work for a living any more. Maybe you already don’t, which is nice for you. But for most people that’s a big deal:

Fig. 2

To be pretentious, although not especially accurate: utility is discontinuous at not having to work for a living.

Other things probably happen too, if you win the Powerball. You can buy a boat or whatever. Maybe a boat is a big deal to you. Something is probably a big deal to you, and if it’s buyable now you can buy it, unless it’s like an aircraft carrier. You can buy love, probably; $600 million is a lot of money.

On the other hand, here you are with a dollar. You could just keep that dollar. How much is that worth to you? I dunno, like, a dollar. A dollar is like a Snickers bar. But it’s not really. Sometimes it happens that a person says “well, I have a dollar, and if I can spend it on the lottery or I can have a Snickers bar, but not both. If I play the lottery, no Snickers for me.”

Wait, the Powerball actually costs $2, but you know what I mean.

But what often happens instead is one of two things. Either you can play the lottery and buy a Snickers bar because you’ve got a bunch of dollars, or money is tight and you weren’t exactly planning to blow your money on Snickers bars anyway before this whole Powerball idea came up.

If you can throw your dollar away on Powerball and still buy all the Snickers you want, how much is that dollar worth to you? If you were going to leave it in the tip jar at the coffee shop, or buy another copy of the Post because you forgot yours at home, how much is it worth to you? Not in dollars — it’s worth a dollar! — but in utility, in things that it will do for your life or that losing it will prevent you from doing. For a lot of people the answer is “a lot.” For a lot of other people the answer is pretty close to “nothing.”

(Oh sure you could skip three $7 lattes every day for a hundred years and thanks to the magic of compound interest you’ll end up with enough to retire on or whatever but I don’t want to hear it. We’re just talking about a dollar here. For the Powerball.)

Calculating “does it make sense to play the lottery” just means weighing the tiny but perceptible benefit from playing the lottery (a very, very, very tiny probability of a very, very big improvement in your life) against the cost — in utility, not dollars — of buying a ticket.

Satisfyingly, this gives a different answer for different people:

1. If winning the jackpot would not materially change your life because you are stonkingly rich, don’t play the lottery, it’s a waste of time.

2. If winning the jackpot would materially change your life because you are a normal person, and throwing away a few dollars every month or so when you notice there’s a big jackpot doesn’t change your life at all because you are financially secure — in other words, if the cost of those few dollars to you in utility is zero — then: play the lottery, why not.

3. If spending a few dollars on the lottery every once in a while would change your life at all — if spending those dollars worries you at all or causes you to cut back on any other necessity or pleasure — then: don’t play the lottery, it’s a waste of money.

Sadly a lot of people who regularly play the lottery fall into category 3. But a lot of people who buy a ticket every once in a while when Powerball gets really big are solidly in category 2. They should keep buying those tickets. They mostly already knew that. An economics that tells them not to is not a real economics.

All of that oversimplifies by leaving out everything but the dollars involved: the pleasure or pain of buying the ticket, dreaming about winning the lottery, checking the numbers, realizing that you didn’t win the lottery, etc. For most people that utility is probably positive, on balance: it’s really fun to daydream about winning the lottery! But for some people the disappointment of losing outweighs the thrill of anticipation.

For those people I can suggest a strategy I once read about, though I can’t remember where. (If you know, tell me!) Here’s what you do:

1. Buy a lottery ticket.

2. Write down the numbers.

3. Destroy the ticket. (I recall the person eating it, though that’s optional.)

4. Wait nervously for the drawing.

5. Check the numbers.

6. Feel an immense wave of relief when you confirm that you didn’t destroy a winning ticket.

This strategy, unlike playing the lottery the normal way, has the advantage that you will almost always “win.” Almost.

Matt Levine writes about the financial industry on the internet at Dealbreaker and sometimes at Planet Money. Sometimes he writes about lotteries. He bought $10 of Powerball tickets on Friday and went back to work again this morning LIKE A CHUMP. Photo: rockinfree

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments