A Conversation with Mark Greif About ‘The Trouble Is the Banks’

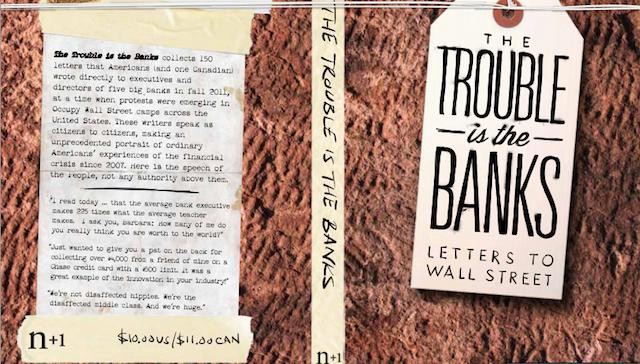

The Trouble Is the Banks is a book of letters written by ordinary Americans detailing their experiences and frustrations with Wall Street during and after the financial disaster of 2007 and 2008. The letters were first compiled by the website Occupy the Boardroom, and the book was edited and put together by n+1. Excerpts have appeared in the New York Times. I consider the book required reading.

The book is available through the n+1 site and, as of today, on Amazon and in bookstores worldwide. I spoke with Mark Greif, a founder and editor of n+1 and editor of the book, by phone.

Logan Sachon: I’d love to hear how you feel about the letters. I spent Sunday reading it and I found it to be terribly depressing.

Mark Greif: Oh no! Well for me of course it’s more interesting to hear your reaction.

LS: Oh, don’t get me wrong. I liked it. I think it’s really interesting, really important. And the things that people are talking about — losing their homes, drowning in student loan debt — I knew these things were happening, of course, I knew the numbers were high. But there’s something different about reading story after story of it.

MG: And there were a number of letter writers that we weren’t able to include, because we weren’t able to reach them for permission. There was one incredible letter, from a guy and his wife, about their house that they loved. He had the letter that he sent initially to the bank, begging them to let him keep his home, and then he had the letter to us, explaining that they had lost it. But we couldn’t find him.

LS: And they all came in through the Occupy the Boardroom site?

MG: When the site initially launched, they put it together in like seven days. So some just didn’t include a name, some had names and info, some had emails, some didn’t. If there wasn’t a name or address and there was identifying information, we’d take that out and run it. But if there was a name or email, we felt like we had to try to get permission.

LS: Tell me how the book came about.

MG: I actually remember the exact night I found the original site. It was late, I’d been around in the occupation here in New York, and I’d watch live coverage of the other Occupy movements. I watched footage of Oakland and of Scott Olsen, the veteran, getting hit in the face with rubber bullets. I was traveling these tunnels of doom on the internet, you know, and I felt like the really specific demands — the concrete desires — were getting overshadowed by police violence and whether or not the protestors had showered or whatever. And then I came to this site and started reading these letters, and they’re all saying exactly what they want, articulating exactly what needs to happen.

I love the democratic way of letters. In the time of slavery, who got to be the postmaster general was a big deal because that’s how people organized. So I read these letters and I was really captivated by them. And then I learned that they planned to deliver the letters to the people they were addressed to, to deliver the letters to the banks. So I went to that.

LS: Just to see it?

MG: Right, not as an organizer, just as a participant. I volunteered to carry some of the letters. I would take them in to the reception desk, deliver them. We started out by the lions, at the 42nd street library, and we didn’t get very far. We got to the Bank of America, and it was barricaded. I was in the back by these guys in suits trying to get in, these Bank of America employees, and I tried to give them some of the letters — hey, guys, these are addressed to you — and some took them, some didn’t.

And then it was over, and I brought the letters that I hadn’t been able to give out home. And I put them on the chair, and I just started to feel guilty that I just had them. And these were just copies, but I felt like the letters could continue to tell this story. And because of my involvement with n+1, I had access to a printing press. So that’s how it started.

We did read all 8,000 letters. I did not read all 8,000, but together we read all of them. A friend loaned me her art studio for the day and I just started to pin them up and that’s how I did the first chapter.

LS: Do you have a favorite?

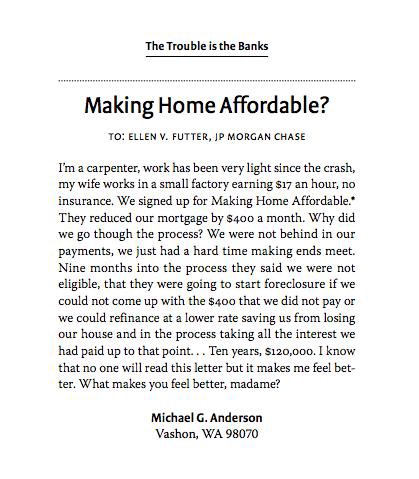

MG: One of my favorites is the letter from the carpenter. At the end he says, “What makes you feel better, madame?” And I just love that.

MG: One thing when you read these letters — if you watch TV, it’s easy to think that people in this country are dumb — but reading these letters, you realize our fellow Americans are kind of brilliant and eloquent. Even someone who doesn’t write much, if given an opportunity to speak on their situation, can do it and be smart and articulate. I love all the people that are over 70 and 80 years old and saying, if I could get out there, I would join the protestors.

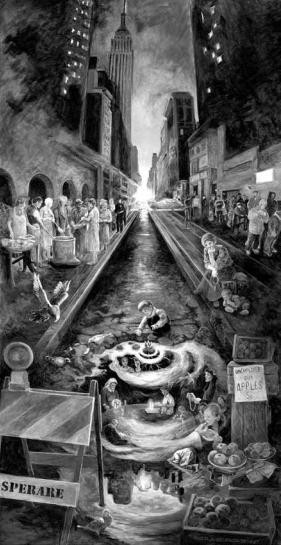

Dayna Tortorici, Kathleen French, and Emma Janaskie, who also worked on the book, really love the letter accompanied by the painting. It was nice that in the process we got a sense of them, just from emailing. And that painting is really good, and very prophetic in a lot of ways. It was done before Occupy and Zuccotti.

LS: Can we talk about the sarcasm in a lot of the letters? There is a lot of it. And it really was starting to bug me — “Oh golly, bank CEO, I am so very excited to have you be my new pen pal” — but then I realized … well, how else can you assert your power, if you’re in this position of asking for help, or explaining an impossible circumstance? You’re writing a letter to a millionaire, the head of a bank. How else can you assert your agency?

MG: If you take a step back, you see these things that are weapons of the weak. Sarcasm. Some are pleading, even if they know that there’s really no chance that it’s going to lead to anything. But maybe it will. Maybe there’s a chance. But someone has to know.

LS: So what’s the plan. You’ve written about getting this book into the bankers’ hands.

MG: I’m very excited — we’re going to mail copies to all of the people addressed in the book. And I think there’s something special about the book, rather than a stack of papers or emails. It’s harder to throw out a book. Books encourage the habit of silent reading, promote consideration. They’re different than letters to the editor in that way. They stick around. I think people might be moved by them.

When I first was working through the letters, there were so many things that seemed wrong, like they must have been mistakes. There is a tendency to side with people who are more organized — the banks, the people in power. And when I looked up up the claims about fraudulent practices — they’re true. I was amazed at my own continued naivete, to disregard kind of, some of the letters. Like, was there really widespread discrimination against the disabled? And I guess it’s called ableism, thinking, there’s no way this is systematic. Because what we found is that it is. That’s why we put in the appendices.

LS: So few of the letters explicitly blame anyone.

MG: Yes. I’m also struck by the personal responsibility people take for themselves. Many admit to buying more house than they could afford, taking out more loans than they could afford. There’s the wisdom of time, and there is something very satisfying in seeing people own their choices, acknowledging they were fully reasonable and rational actors.

No one denies that American life is better and richer than 50 years ago, but the foundation that should be built under this isn’t there. It turns out I have a strong congenital optimism. I don’t think I’d seen the right to assembly used in my lifetime, and now I have. And to see it is inspiring.

People ask me if it makes a difference for people to read this book — executives at banks, legislators. And I don’t know. But I do feel that there is a lot of be hopeful for in that the middle-level level people in banking and finance and government, they’re the ones who are really making a lot of these very tiny decisions. I think people that work in banks are good people. I do think the heads of organizations can be ideologues, but I think most people are good people.

Someone asked me today, do you think it’s all over, that the only chance to do anything meaningful was in 2008, and we missed it? And I said, yes, 2008 was an opportunity. The absolute disaster of 2008 was an opportunity. But I don’t think all is lost. And well, another crash seems possible. Not that I’d want that, but who knows. It’s a time of change. I’m a literary person. I spent my whole life trying to avoid thinking about finance.

Mark Greif is a founder and editor of n+1. You can buy The Trouble Is the Banks from n+1 and on Amazon. You can also make a tax-deductible donation for a copy to be given to a banker at the n+1 site.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments