My Conventional Career History

Photo credit: growdigital, CC BY 2.0.

I’d like to say that my story is an inspiring tale of pluck and perseverance as I overcame Herculean obstacles on my way to fame and glory, but I can’t. I’d like to deliver a morbidly fascinating cautionary chronicle of poor life choices, crippling debt, and worthless education, but it’d be a lie.

Instead, my career history is quite possibly the most boring and conventional one possible. When somebody is lecturing Millennials on everything they are Doing Wrong, I expect my path is sort of what they have in mind as what they think everybody could achieve If Only They’d Apply Themselves. (Yes, I know that’s not how the world actually works.)

The story starts in a conventional way; I had a suburban middle-class upbringing in a DC suburb; my Dad was a federal civil servant and my mother a homemaker. While we were by no means poor, we certainly were not rolling in the dough; we lived in the smallest townhouse on our block and our two cars were a VW Microbus that was as old as I was, and a ratty-yet-reliable mid-80’s Honda Civic Wagon; those cars would stay in the family until I was nearly graduated from college.

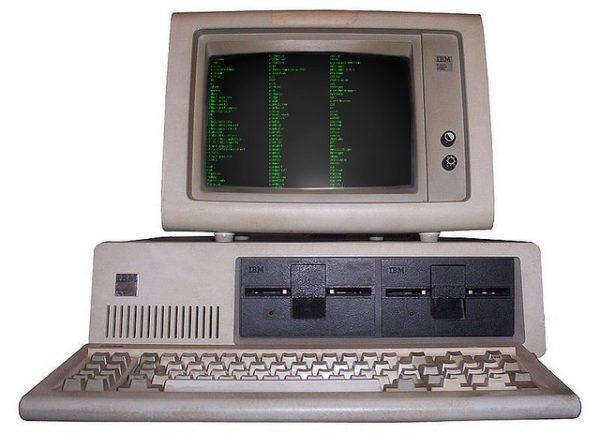

Future-career-wise, I was blessed very early on; when I was still in elementary school, I knew that I was going to do something related to computers, and I didn’t seriously waver from this even once. My parents always had a computer of some sort in the house, starting with a succession of various chintzy home computers; they bought our first PC in ‘89.

I was a reasonably bright student, but had what today would probably be diagnosed as ADHD and, much to the consternation of my parents and teachers, a great aversion to doing homework; I graduated from my decent suburban high school in 1995 with a respectable, but by no means exceptional, GPA. With my single-minded career track, I filtered prospective colleges based on whether they had a Computer Engineering program—and this was by no means universal at the time. Despite the whole family going to VA Tech, I found a slot at Lehigh, a decent private school with a generous financial aid policy. Their formula was (and still is): “Fill out the FAFSA, pay the EFC, collect whatever grants/federal loans/work-study the FAFSA gives you, and we’ll write off the rest.”

During high school and college I never had a summer where I was idle, spending a total of five summers as a poorly-paid staff member at a Cub Scout camp. I also had an after-school job repairing video arcade machines my senior year in high school. (As a dedicated tech geek, they hardly needed to pay me for that!) In college I worked the help desk in the computer lab and did tech support for students trying to connect to the campus network. In these days of ubiquitous WiFi that takes about 30 seconds to set up, you might wonder how much support was involved, but at the time (late 90’s), it took some serious skills to consistently attach PCs to the internet and the campus network.

I spent one summer working for the Dept. of Defense, where I was a PC tech at the Pentagon. (Fun fact: The “hotline” between the US and Moscow is not a bright red phone in the Oval Office. It’s a very bored military officer sitting in front of a computer in a closet in the Pentagon. No, they didn’t let me touch that computer.)

To take that Pentagon job, I turned down an informal offer of a paid internship with a tiny little company called AuctionWeb that specialized in used computer parts and random knick-knacks. Today that company is called eBay. Oops.

The next summer, gainful employment consisted of working for an Army contractor doing some website work. My one claim to fame was I once got to edit the homepage for army.mil (using Windows Notepad!) when the regular webmaster was out sick.

Notice both of those summer internships were paid! I cannot imagine how difficult it must be to round up money for the school year without the ability to make money during the summer. I’m very grateful for both of those opportunities; like many tech geeks who lord their skills over mere users, I was at times obnoxious and immature (they didn’t ask me back the next summer at the DoD) and it’s certainly better to work that out of my system with temporary summer jobs vs. getting fired from a regular job.

I graduated with a middling GPA at the end of four years, but times were flush and employment wasn’t a problem because this was the peak of the “dot-com boom,” where literally any company that could even pretend to have something to do with the Internet was pretty much minting money. That bubble popped in the spring of 2000; I’m very lucky I didn’t graduate the following year! About the only well-off survivor of that bubble is Amazon; no other company caught up in that hype ever fully recovered. (Do you young whipper-snappers of today even remember Netscape, or when AOL had enough money to buy Time-Warner?)

By the fall semester of my senior year, I had landed an offer to choose between three positions at a large computer company of which you have all heard. It may seem hard to believe with the job markets of today, but as an average student (although one with a solid resume), I had offers from five different companies without even digging that hard, although none was better than that first one. I don’t know a classmate in my program that graduated without a job in-hand if they didn’t want to go to grad school—and only a few people chose grad school.

My first task at the company was doing top-level tech-support for network equipment, and despite never having done anything substantive with a piece of network equipment in my life, I took to the job quickly. (This is typical for newly-minted computer jockeys; college is no more a vocational school for us than it is for liberal-arts majors, even if the employment prospects are brighter.)

Soon after I started work, the division I was employed was essentially shut down; it’s hard to describe how terrifying it is to be reminded that as a wet-behind-the-ears college hire, you are literally the youngest and least experienced worker in a division with 1,200 employees, most of which were about to lose their jobs. (I would remain the youngest employee in my business unit for another five years.) With 20/20 hindsight, tech support turned out to be the best possible choice, as there was still equipment we had already sold that needed continuing support.

My management soon found a niche for me working on some different equipment (that we still sold), and I spent the next 13 years working on that, with a steady succession of raises and promotions; I even have co-authorship of a half-dozen technical books written on behalf of my employer.

Fast-forward to about four years ago when a former co-worker let me know of a position opening up in his department in another division, which let me crawl out of tech support and finally take on the role I had always wanted since college: doing IT Architecture. I’ve been doing that ever since.

The end result of all this is a comfortable middle-class life with my lovely wife. (I met her at work; she was a developer for the equipment I was supporting at the time.) We live in a nice home in leafy suburbs of a city with a reasonable cost-of-living. No kids, but the house is ruled by two adorable kitties. While I would not refer to us as “rich,” I wouldn’t object to being called “well-off;” our income and assets are solidly in “the 10 percent,” we live well below our means (we could get by on one of our incomes), and are on-track for retirement in our 50s.

I won’t pretend that my career history is solely due to personal virtue or brilliance; certainly privilege and no small amount of luck have had a lot to do with my success.

- My passion is a field which also happens to be lucrative

- That passion is something I’m really good at

- I locked onto my eventual career at an early age

- I’m male

- I’m white

- I had a solid middle-class upbringing from two college-educated parents

- I successfully dodged many rounds of layoffs and industry downturns; some of that was skill, most of it was pure, blind, luck

I’ve leveraged all that to form a solid career at a single company for nearly 20 years, an outcome that used to be considered par-for-the-course and is now rare even amongst my generation, and I understand that particular brass ring is nearly unfathomable to somebody graduating college today.

All that said, the future looks to be a very interesting place, and I look forward to seeing what today’s young adults do with it.

Peter Mescher is an IT Architect in North Carolina. Since he’s inexplicably a social-media Luddite, you won’t find him on Twitter or Facebook, but you can spot him in discussion groups and comment sections all over the Internet as “SirWired.”

This story is part of The Billfold’s Career History series.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments