Hong Bao Season

I’m almost too old for this.

Last week, my mother texted me a picture of a receipt, with totals circled in pen and underlined.

“Red envelopes on the way,” she wrote. “Please let me know when you receive them.”

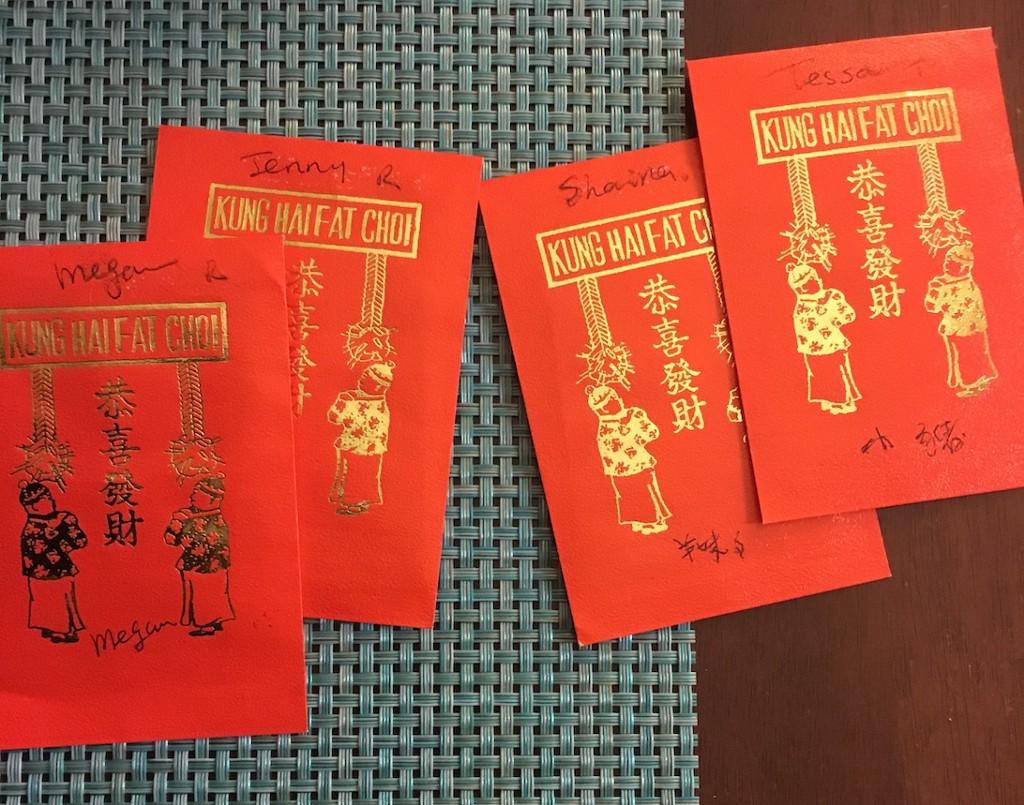

She had paid an astonishing $78 to insure that the envelope made it to us in time, partially because sending money in the mail feels like you’re asking for it and partially because when she sent $200 to my grandma in Taiwan, the money never made it there. On Saturday, four identical red envelopes arrived at my house, each stuffed with a crisp $20. That was our hong bao money, encased in crimson, a tiding of good luck and good fortune for the new year.

2017 is the year of the fire rooster. It’s my mother’s year and that means she’ll have to be extra careful. You’d think that your year would be auspicious, but tradition states that your year is a very unlucky year, indeed. When we were little, my mother told us to wear red underwear during our year and to be extra careful. Danger lurks everywhere, waiting around every corner. In Oregon, where my mother lives, it’s been snowing. My mother is a terrible driver under clear blue skies; the thought of her maneuvering a minivan through the streets of Beaverton, negotiating pockets of ice and snowdrifts terrifies me.

“I have to be careful this year,” she told me. “I don’t know how to drive in snow. It’s bad luck.”

The tradition of the red envelope is less about the money contained within and more about the envelope itself. Red is good luck and so wrapping the money in red is extra special, as a ward against the miasma of bad luck and misfortune that swirls around everyday life. Red is a safeguard; it’s a balm. The money in the envelope doesn’t matter; like most things in life, it’s the intent that counts.

I’m likely way too old to be still receiving red envelopes from my mother. At some point in the past five years, the tables should have turned. My sisters and I have jobs and are earning money; we’re also all old enough to know better. None of us are married and none of us have children, much to my mother’s increasing chagrin. In her eyes, we’re adults, but won’t be fully-formed until we’ve experienced motherhood or the quiet, patient drudgery of marriage — maybe that makes it okay. So we get the red envelopes, we eat dumplings and noodles and celebrate in our own ways.

“We don’t have to send Mom money until we have kids,” my youngest sister told me with the calm self-assurance of someone who has convinced herself that a falsehood is definitely the truth. We should send money to her out of some distant sense of filial piety, or because she’s our mom and could probably use it. Next year, I will.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments