What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: L.M. Montgomery’s ‘Rilla of Ingleside’

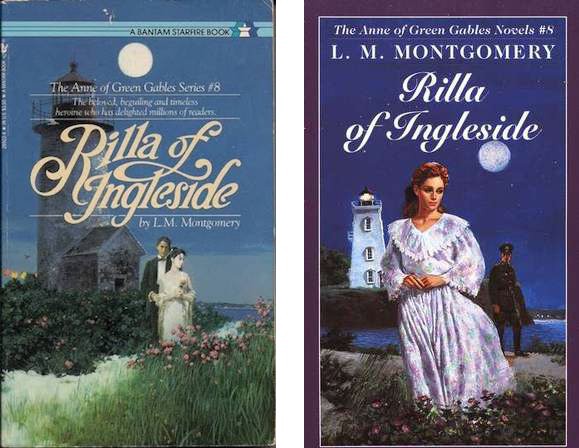

Rilla of Ingleside may be my secret favorite of L.M. Montgomery’s Anne books. I avoided reading it as a child, because the cover made it look like it was about weird old people—you know, in their twenties or something—and so I didn’t read it until I was in my twenties.

Then I loved it. I still think the cover is completely wrong, and the updated cover is only marginally better. Rilla Blythe, Anne and Gilbert’s youngest daughter, does not view the world with shy, downcast eyes. She looks problems in the face and gets them done.

In this case, the problem is World War I.

It should be obvious why I chose this book, for this week: a young, privileged white girl finds herself no longer able to avoid politics—or the work required to help people in need. Although Rilla can’t cook, can barely knit, and hates the telephone, she decides she’s going to give as much as she can to the war effort. This includes not only knitting hundreds of socks and starting a Junior Red Cross, but also becoming the primary caretaker of an orphaned “war-baby.”

Montgomery is the kind of writer who always sides with her heroines, despite their faults, and fifteen-year-old Rilla’s initial fault is that she doesn’t really consider much beyond her own immediate concerns. Rilla is happy enough to be the one Blythe child who is, as she puts it, “unambitious.” She’ll just get married, you know? Her older siblings went to college to become teachers and doctors, but Rilla doesn’t have to do that, because someday she’ll have a husband to provide for her.

Then the war happens. Rilla finds it hard to believe that people in her small hometown are being asked to fight to preserve the rights of people who are so distant from her that they almost seem unimaginable, but the news is real and unavoidable—and Rilla, at her core, values other people and believes in human rights, even if she’s never thought about them too carefully before. So she decides to do everything she can to help.

Helping, in this case, includes donating money. It also includes sewing bandages, knitting socks, sending care packages to the front, and so on. The Blythes dig up their flower garden so they can grow potatoes for the war effort. They eat rationed food so other people can have more.

They also ration their own pleasures. When Rilla buys herself a new hat to replace a worn-out old one, she ends up selecting a green velvet hat that costs more than she had planned to pay. As she writes in her diary:

The price was dreadful. I will not put it down here because I don’t want my descendants to know I was guilty of paying so much for a hat, in war-time, too, when everybody is—or should be—trying to be economical.

Later she has a conversation with her mother (you know, Anne):

“Do you think, Rilla,” mother said quietly—far too quietly— “that it was right to spend so much for a hat, especially when the need of the world is so great?”

“I paid for it out of my own allowance, mother,” I exclaimed.

“That is not the point. Your allowance is based on the principle of a reasonable amount for each thing you need. If you pay too much for one thing you must cut off somewhere else and that is not satisfactory. But if you think you did right, Rilla, I have no more to say. I leave it to your conscience.”

I wish mother would not leave things to my conscience!

Rilla ends up telling her mother that she will essentially amortize the cost of the hat by not buying another one for three years or the duration of the war, whichever is longer.

To be fair, keeping the local milliner in business is just as important, in its own way, as donating money to help the Belgians. This point is made even more clear when Rilla volunteers to work, assumedly unpaid, at a dry goods store so it can stay open. The global economy and the local economy are intertwined, and the people in Glen St. Mary watch out for each other. They help neighboring farms get their harvests in, since the young men who would be doing the work are at the front.

While we’re on the subject of help, we need to mention Susan Baker, the Blythes’ live-in housekeeper, cook, and maid-of-all-work. If there’s anything the Anne books teach us about money, it’s that marrying a well-paid doctor who’s willing to hire a live-in housekeeper can free you from a lot of domestic labor. Think of Marilla, spending all of those hours teaching Anne how to wash dishes and make biscuits! Now Anne has someone to wash and cook for her, as well as mispronounce the names of French and Russian cities because she doesn’t know any better.

Not that Susan is ever treated as an inferior character, pronunciation jokes aside. Here’s how Montgomery describes her:

The wind whipped her grey hair about her face and the gingham apron that shrouded her from head to foot was cut on lines of economy, not of grace; yet, somehow, just then Susan made an imposing figure. She was one of the women—courageous, unquailing, patient, heroic—who had made victory possible.

And what would a woman like Susan have done, if there hadn’t been a Blythe family to hire her? She, unlike Rilla, was not interested in marriage, and she didn’t have the educational background to become a teacher or a nurse. Working for the Blythe family gives her independence, in the sense that she is earning her keep instead of being reliant on, say, a relative taking her in. Susan is vastly more skilled at her work than Anne would have been (something something liniment cake), she’s earning income, and she is valued and loved.

Susan’s independence and value also lets her make her own decisions, such as her choice not to observe the newly-invented Daylight Saving Time. Yes, her aversion to Daylight Saving Time is written as comic relief, but we all agree with her.

What else does Rilla of Ingleside teach us about money? Anne kind of sums it up in her “If you pay too much for one thing you must cut off somewhere else” statement: if you spend too much on a hat you have less money to give the war effort. If you use up your sugar ration making fudge, you’ll have to do without later. As Susan reminds us, if you save daylight in the morning it will get dark earlier.

But you can also generate wealth: if your friend is getting married, you can make over your white dress to fit her. If you dig up your peony beds you can plant more potatoes. If you care for an orphaned infant you cannot go out dancing with your friends, but you can see a child smile at you for the first time.

Before I close this out, I have to address the “fifteen-year-old Rilla adopts an orphaned infant” thing, because it always bugs me. Not that it isn’t a generous and noble thing for Rilla to do, but the “we better bring this woman back to reality by giving her an unexpected baby” is such an overused plotline. (Mad Men used it for all three of its lead female characters.)

And yeah, that’s what baby Jims does. That’s his function in the story: to connect Rilla to the idea that there is a larger world outside of herself, and that she has to participate in it even if it means giving up time and sleep and leisure—because if she doesn’t, a baby will die.

But Rilla had otherwise assumed that she would eventually get everything her parents had—a happy marriage, a comfortable home, a full-time live-in housekeeper—without having to work for it. She had thought that her life would start at the apex of her parents’ lives and move up from there, and then the war happened, and everything changed, and Rilla found herself no longer able to predict the future.

So she decides to do everything she can to help.

Which is why I chose this book for this week.

Previously:

What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: Maud Hart Lovelace’s ‘Betsy’s Wedding’

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments