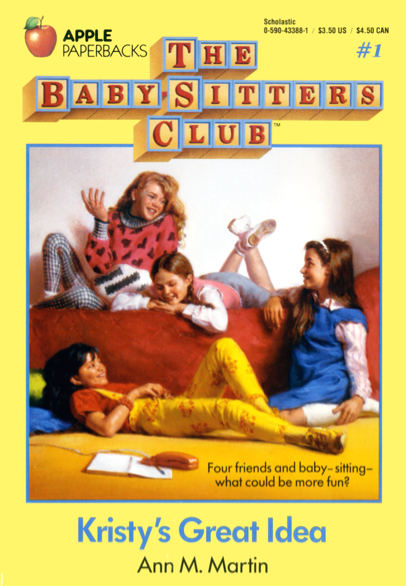

What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: Ann M. Martin’s ‘Kristy’s Great Idea’

Also: can we figure out how much the sitters were earning per job?

So this week’s installment was inspired by an article I saw on Autostraddle:

Baby-Sitters Club Creator Ann M. Martin is Queer, How Did I Not Know This | Autostraddle

Which, first of all, that’s awesome, and second of all, OMG I have to read the first BSC book again to see what it says about money.

Since I remember the Baby-Sitters Club books primarily as formulaic sequels where you could literally skip the first 20 pages, I was surprised at how smart the first Baby-Sitters Club book was. Of course kids are going to love this. Of course I loved it when I was nine years old.

Yes, every plot point is telegraphed as blindingly as the flashlights that Kristy and Mary Anne use to send secret messages from their bedroom windows. But we never really read The Baby-Sitters Club for the plot. We read it to see ourselves reflected in the characters, and to imagine ourselves in a world where twelve-year-old girls are taken seriously.

The novel starts by explaining why the adult characters have to take these twelve-year-old girls seriously: because they’re the ones who control a valuable asset. When Kristy’s mom has to work late, it is a significant problem if Kristy is not available to babysit her little brother David Michael. Sure, Kristy’s mom could spend the entire night on the phone calling up every other twelve-year-old in town, but that’s a huge waste of her energy and resources.

Kristy recognizes this, so she comes up with a solution.

Kristy’s “great idea,” if you are completely unfamiliar with any aspect of The Baby-Sitters Club, is to set up a centralized number that all of the local parents can call when they need a babysitter. The person at the other end of the number has a master schedule of all the sitters’ availability, and can let the parent know immediately if a sitter is free. The parents can request a specific sitter, meaning that certain sitters might get more opportunities than others, but sitters can also take notes on their experiences and blacklist families that don’t treat sitters well.

Kristy has essentially created Uber. (Or any type of employment agency, really.) Like Uber or other gig economy companies, the Baby-Sitters Club members have to pay part of their earnings back to the company in the form of weekly dues, which are used to keep the business running and buy a shared pool of babysitting supplies. The sitters are also occasionally asked to contribute additional earnings to the club, for pizza parties.

These pizza parties turn out to be a huge point of conflict in Kristy’s Great Idea, for two reasons. Mary Anne’s father, who we’ve been informed is very strict, refuses to let his daughter waste $3 on pizza. Stacey, meanwhile, can’t eat pizza because, as we eventually learn, she has diabetes.

Which, honestly, is kind of fascinating in terms of “what our workplaces ask of us.” In Kristy’s Great Idea, we learn that both Stacey and Mary Anne can solve their problems if they just communicate (Stacey by explaining diabetes to the rest of the club, and Mary Anne by convincing her father to let her spend 50 percent of her babysitting earnings if she saves the other half), but what’s unspoken is that both Stacey and Mary Anne had to have uncomfortable, unwanted conversations simply because their employer wanted to throw a team-building pizza party without considering the employees’ financial or physical needs. Even at twelve years old, mandatory workplace fun is anything but.

So, the final question: how much do these sitters earn, and how much are they paying back to the club? Martin is deliberately unclear about what the sitters make per hour or how much they pay in weekly dues, but we know that $3 is apparently enough of Mary Anne’s income that her father thinks spending it on a pizza party is a big deal.

Kristy’s Great Idea was first published in 1986, so that $3 would be $6.59 in today’s dollars. I wouldn’t be surprised if it represented more than an hour of babysitting work, especially considering that the 1986 federal minimum wage was $3.35.

So, okay. We can almost figure this out. The sitters have three club meetings a week, and each sitter gets roughly one babysitting job per meeting. This means each sitter is babysitting three times a week, give or take, and if they’re earning $1.50 an hour for what I’m going to estimate is six hours of weekly babysitting work, that comes out to $9 a week.

Let’s say they pay $2 per week in dues, leaving them $7 in income—which makes that $3 for pizza a huge expense. Even if you do the math a little more generously, giving the sitters $2 an hour and only $1 in weekly dues, that still means they only earn $12 per week and keep $11, and spending $3 on pizza means giving up more than 25 percent of their income.

But that doesn’t matter to the Baby-Sitters Club, because they were never really in it for the money. They were in it for the friendships—and because it was a way for them to establish their own power and agency in a world that rarely assumes young girls are capable of either.

When I read these books and dreamed of starting a Baby-Sitters Club of my own, that was exactly why.

Previously:

What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: Beverly Cleary’s ‘Otis Spofford’

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments