Would A Mandatory Retirement Age Help (Most) Academics?

Surplus PhDs + tenured profs refusing to quit = chaos

Are you pursuing a PhD right now? The New York Times hopes not.

The lure of a tenured job in academia is great — it means a secure, prestigious position directing a lab that does cutting-edge experiments, often carried out by underlings. Yet although many yearn for such jobs, fewer than half of those who earn science or engineering doctorates end up in the sort of academic positions that directly use what they were trained for.

Fewer than half! With that stat, and others, the article focuses on how bad things are in the research-y STEM fields in which so many bright, studious people are wasting their youth. Some choice, terrifying quotes:

- “For every new Ph.D. who gets a tenure-track academic job, 5.3 will be shut out.”

- “Biomedical scientists in academia are essentially apprentices until middle age.”

- “84 percent of new Ph.D.s in biomedicine ‘should be pursuing other opportunities’ — jobs in industry or elsewhere, for example, that are not meant to lead to a professorship.”

Of course the situation for new PhDs in humanities and the arts is even worse because, outside of academia, there are even fewer places for wannabe-professors to get jobs. Perhaps you remember this iconic piece in Slate by William Pannapacker?

higher education in the humanities exists mainly to provide cheap, inexperienced teachers for undergraduates so that a shrinking percentage of tenured faculty members can meet an ever-escalating demand for specialized research. Most programs are unconcerned about what happens to students after they graduate, and it’s not pretty. In all likelihood, a humanities Ph.D. will place you at a disadvantage competing against 22-year-olds for entry-level jobs that barely require a high-school diploma. A doctorate in English that probably took you 10 years to earn is something you will need to hide like a prison term while you pay off about $40,000 to $100,000 in loans. Your consolation: deep thoughts about critical theory.

Despite the controversy that followed, Slate doubled down, publishing at least one more cheerfully morbid, declarative piece (“getting a literature PhD will turn you into an emotional trainwreck, not a professor”). Elizabeth Segran at the Atlantic then took Pannapacker and his ilk to task, pointing out that:

between a fifth and a quarter of them go on to work in well-paying jobs in media, corporate America, non-profits, and government. Humanities Ph.D.s are all around us — and they are not serving coffee. … Preliminary reports released in the past few months show that 24.1 percent of history Ph.D.s and 21 percent of English and foreign language Ph.D.s over the last decade took jobs in business, museums, and publishing houses, among other industries.

Still, the fact that 1 out of 4, or 1 out of 5, humanities PhDs doesn’t end up broke and miserable is not much solace. Pannapacker’s larger point, whether or not it was overstated to make an impact, is that academic prospects are bleak. Segran cannot dispute that.

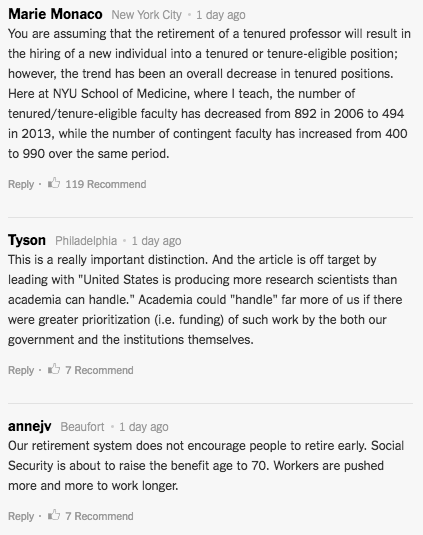

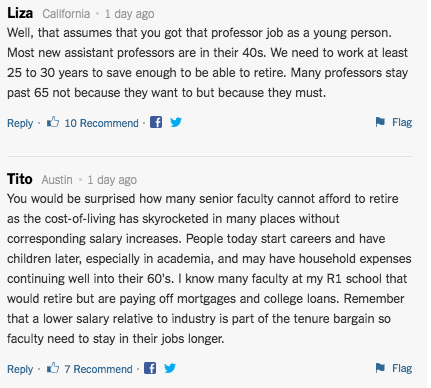

So, okay, lots of problems. Any solutions? Well, one, maybe. Someone in the comments section of that original Times piece seized on the fact that tenure track jobs are especially hard to get these days because the people lucky enough to have those rent-controlled apartments in the Ivory Tower are sure as hell not going to give them up. Couldn’t that change?

Six words in this article really stand out for me: “faculty members retiring later and later”. That is a big problem today. Surely they should retire from their tenured, full-salary positions at some age (say 65), open those positions for younger scholars, and then let the retired professors be the ones to continue to do good scientific work (with research awards, etc.) for lower, postdoc-type wages. They can still do good work, and still be a member of their academic community. But step aside job-wise for the young.

The answer seems to be a resounding, “No!!”

Some of these arguments are more compelling than others. If tenured profs were told coming in that they would be asked to retire between, say, 65 and 70, they would be more likely to plan accordingly and so not get caught off guard in terms of expenses and retirement. The fact that schools are not hiring tenure-track professors at all is more of an issue: the over-reliance on adjuncts is an endemic problem that academia needs to pull together to figure out how to solve. But I’m not swayed, at least not so far, by the notion that a tenured professorship should be like a seat on the Supreme Court. If it might open things up for the (slightly) younger generations, maybe a suggested retirement age — or age range — is worth trying.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments