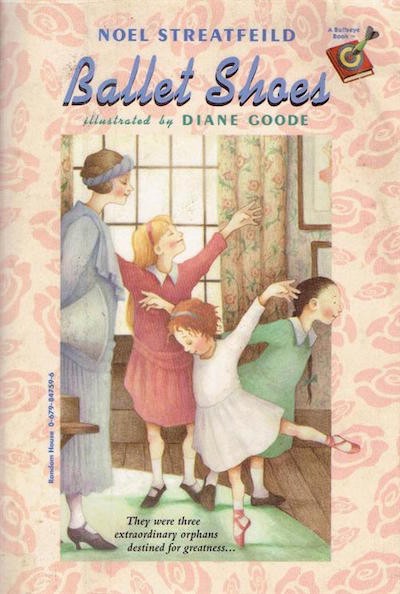

What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: Noel Streatfeild’s ‘Ballet Shoes’

Hold your thumbs for luck.

A quick note about why we aren’t doing Return of the Great Brain this week: my mom sent me a package with my childhood paperbacks of both Great Brain and No Coins, Please, but the package never arrived. (We’re still hoping we can figure out what happened.) So I pulled an old favorite off the shelf instead.

When I was a child, I thought of Ballet Shoes as a training manual. It had everything I needed to know about how to act (stand in front of a mirror until you no longer see yourself but instead see the character you’re playing; also, spend as much time as possible watching more experienced actors rehearse), and everything I needed to know about how to function in a professional environment (everyone can be replaced, so don’t get cocky; also, know when to ask someone in charge for a special favor).

It also taught me that sometimes it’s important to save money and sometimes it’s important to spend what you’ve saved.

Especially if spending those savings can help further your career.

In case you’re not familiar with Ballet Shoes, here’s a quick plot summary:

A young woman is given three (unrelated) orphaned babies by her uncle, whose home she manages while he travels the world. The uncle then disappears, leaving the young woman to figure out how she is going to raise these children without any income. She takes in boarders, each of whom is coincidentally skilled in one of the children’s particular talents. The boarder who is also a professional dancer suggests that all three children train as child actor/dancers, so that they can start earning money for the family.

The oldest child, Pauline, becomes a talented actress (and a talented enough singer and dancer) and keeps the family afloat through her skill and her hustle. The middle child, Petrova, picks up chorus parts for the cash while studying to become a pilot. The youngest child, Posy, only wants to dance ballet—and she wants to become one of the best dancers in the world.

When I loaned my copy of Ballet Shoes to my college mentor, she told me afterwards that she thought I was Posy, because I wanted to make art more than anything (and, I will kinda mumblebrag, “because Posy is the genius”).

I always, from the very first read, identified with Pauline—who also wants to do work that has artistic merit, incidentally. But she knows both her talents and her limitations, and she’s ready to take any available job. Sometimes she makes art, but she always makes money.

Pauline is also the one who knows when to spend money. The book devotes several pages to explaining the “child actor working world” — including a reproduction of a child actor license — and one of the stipulations is that a child actor must put at least a third of their earnings into a savings account. The minute Pauline is no longer considered a child (that is, when she turns fourteen), she announces that she is no longer putting any of her money into savings. “And what’s more, if we need it, I’ll take out what I’ve saved.”

Some of that money goes towards supporting the household, but Pauline also uses her earnings to study theater. She gives some of the money to Posy so she can go to ballet performances. (Petrova also gets her share, don’t worry.) At the end of the book, Pauline signs a five-year film contract, giving up her dreams of performing Shakespeare, so that Posy can have money to train with a premiere ballet company.

Streatfeild is very clear about how little money this household has, even with the boarders and the income that Pauline and Petrova bring in. This is a household with shabby furniture and plain meals and patched clothes.

It’s also a household with a cook and a maid (and Nana, the live-in nanny who’s been with the house for generations and nobly refuses a paycheck when they fall on hard times). They might not have a lot of income, but they’re not poor.

To make sure we understand this—that a household in which three girls agree to pawn their jewelry so that Pauline can have a new dress for an audition that might bring them more money is not poor—Streatfeild gives us Winifred.

Winifred is more talented than Pauline. Both of them know this. But Winifred’s family is poor—or poorer, anyway. They don’t have gold watches to sell or necklaces to pawn. They don’t have extra rooms for boarders. They can’t buy Winifred a new dress, and so Pauline gets cast instead of her. Then, at the next audition, Pauline has more experience and thus has the advantage. And so on.

Pauline signs a five-year Hollywood contract. Winifred becomes a dance teacher. (If you don’t remember that from your copy of Ballet Shoes, it’s because she appears again as a minor character in Theater Shoes.)

Like The Boxcar Children, one of the big attractions in Ballet Shoes is the idea of children taking on adult responsibilities. Starring as Alice in Alice in Wonderland might be thrill enough, but the fact that Pauline is earning money, and that the story spends four pages detailing how much money she earns and how it’s divided among savings and household expenses? THIS IS EVERYTHING I EVER WANTED.

The part that surprised me on the re-read was how much help the adults provided. I took it as a given, as a child, that if an English professor moved in to my house, of course that person would teach me Shakespeare. Now, I’m impressed—and kind of humbled—that the group of adults living in this house formed their own family and agreed to support each other and the three talented children living with them.

Which might be the part of the manual that I need to take with me into the next stage of my life. I’ve learned how to hustle, how to work for both art and money, and when to spend what I’ve saved. I still have a lot to learn about how to give back.

It’s a good thing I’ve got this book to teach me.

Previously:

What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: Betty Smith’s ‘A Tree Grows in Brooklyn’

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments