How Not To Pay Your Student Loans

When I was interviewed for The Billfold’s “Doing Money” series, I included a few off-hand comments about debt, basic income, student loans. Maybe the short-form answers came across as more flippant than I intended, but I was surprised to see so many critical responses from Billfold readers.

How a Freelancer in a Portland Co-Op Does Money

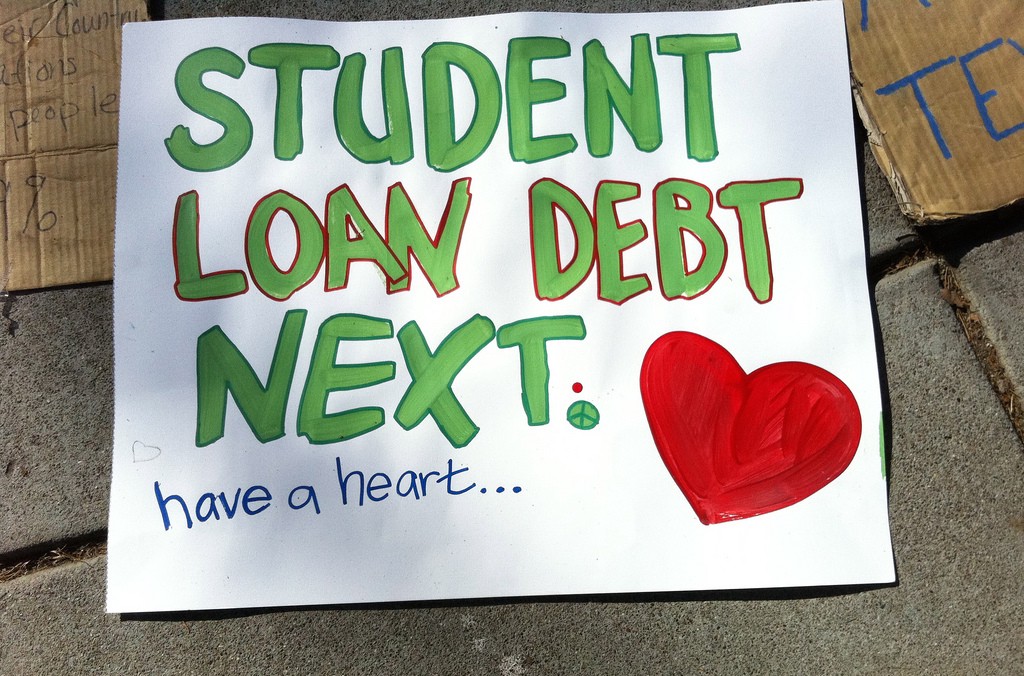

I mentioned that I intended never to pay off my student loans because I’m on an Income-Based Repayment Plan that will forgive them after 25 years of making payments — even if those payments are zero. It may be the case that my income increases over the next few decades, and that I will pay something each month, but it seems unlikely that I’ll earn enough to ever pay off the remaining balance in full.

In fact, it makes more sense for me to earn under a certain level of income each year so that I can put my money toward future expenses (like securing my place in a housing co-op) rather than past expenses. That’s the calculus that I — and many other students who graduated into the recession — are working with.

And because my college degree turned out to be pretty useless overall (we’ll get to that in a bit), I feel morally justified in withholding my payment.

One commenter replied:

“In what world does this make sense? If I buy a sweater I never wear I still have to pay for it.”

Let’s put aside the vast difference in price tag for a minute. If your sweater had a label that read “Made in America. 100% cotton. Lifetime guarantee,” and then you found out it was made in an overseas sweatshop with toxic synthetics and needed patches after six months, you’d be pissed too.

That’s how a lot of my peers feel about college: we were given glossy brochures that outlined overly-optimistic career paths; taught technologically outdated skills; and offered very little support in adapting to the post-recession economy.

When I applied for my student loans, I was 17 years old. I’d lived in the same town my whole life, and had barely traveled outside of New England; my high school job was working for the small family business that my dad owned and operated.

Could I have made better choices if I’d had more real-world experience? Maybe — but I did the best I could with the information I had.

I turned down a mediocre financial aid package from an expensive Ivy League school to accept a moderately better one from a less prestigious liberal arts college. I chose the career path (writing and media arts) that my teachers — from grade school all through high school — had told me I excelled at.

If I had told anyone that I planned to get married, have a kid, or buy a home at that age, no doubt my parents and guidance counselors would have done all they could to talk me out of it. But signing a student loan package — an equally life-long commitment — was just par for the course.

Since I don’t believe that I was able to give informed consent in signing for those loans, I don’t consider it a valid agreement worth honoring.

Another commenter wrote:

“If you truly believe you learned nothing from your degree, that’s on you.”

While I said in my interview that my college degree didn’t help me with my career path, I didn’t say I learned nothing from it. And I didn’t pay nothing for it, either. My student loans were just a portion of my tuition, fees, and other expenses.

The amount of money I’ve paid already, including some initial loan payments, is, in my view, a fair amount for the education I received there.

But let’s be clear: the metric by which we judge the value of an education shouldn’t be whether or not we “learned something”. If I pay thousands of dollars for a car and it breaks down the next day, I wouldn’t expect someone to say, “Well, at least it got you somewhere. If it stops working now, it’s on you.”

I’d look up the local lemon laws.

In my case, it was pretty obvious within months of graduation that I hadn’t received the education I had been promised. My professors weren’t up-to-date on the latest technologies — many of the tools we’d used were becoming obsolete. Our Career Services department was as helpful as the DMV.

Maybe I should have recognized this earlier and dropped out after my freshman or sophomore year. But can you imagine how my parents would have responded to that? By this point, I was all in, and the rest of my savings went toward senior projects and a semester of unpaid internships.

My college education was a lemon. And the Income-Based Repayment Plan is the closest thing we have to lemon laws for junk college degrees.

Now, if you’ve been paying your student loans for years, I can understand why you might look at debt resisters like me and think we’re freeloaders. But to me, the real freeloaders are the financial institutions earning interest off of our bad fortune.

I see college grads like me as canaries in the coal mine.

We’re a symptom of what happens when a wealthy country doesn’t provide the option of a free college education to its citizens, or to offer graduates the safety net they need in a precarious job market.

I don’t think this situation is going to get any better for future generations, and we’re likely to see even more defaults and deferrals in the coming decades.

Even if you’re able to make your monthly loan payments now, it may still make sense to apply for the IBRP. You never know when circumstances will change — and if they do, you’ll be glad you got that 25-year countdown started.

And if you have kids of your own? Go ahead and send them to college in Slovenia.

Saul is a freelance writer living in an urban eco-village in Portland, OR. He blogs about intentional communities at www.ic.org, and about debt, freelancing, basic income, and other topics at Medium and on Twitter.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments