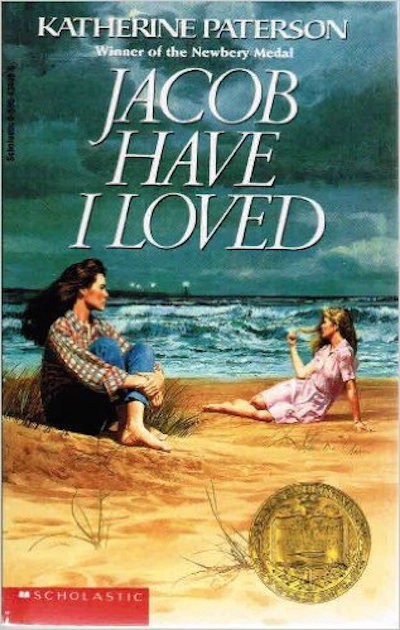

What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: Katherine Paterson’s ‘Jacob Have I Loved’

Sara Louise’s work pays off in cash from the crab haul. Caroline’s work pays off when she receives a full ride at Juilliard.

I was always a Caroline.

Petite, talented, able to take charge and move confidently (or at least pretend-confidently, I was a teenager after all) through the world. In school I got the solos and won the awards. In college I got the full ride scholarship.

And yes, I’d love to read this same story from Caroline’s point of view, maybe in one of those books that you flip over halfway through, the kind with a front cover for both Bradshaw twins.

But the genius of Jacob Have I Loved is that readers can identify with Sara Louise even if we are secretly Carolines.

Maybe we’ve spent our summers sweating through jobs and stashing away savings. (I’ve done that.)

Maybe we’ve dreamed about leaving our hometowns and going to boarding school, even though we think our parents would never let us go. (I’ve done that too.)

Maybe we’ve watched someone more popular than us laughing with one of our best friends, or discovered a sibling using our stuff without asking, or had a crush on a teacher or family friend. (I’ve done all of that. I’ve also been the sibling who used the stuff without asking.)

I want to know what Sara Louise did with the $50 she saved for boarding school. (This was in 1942 dollars, meaning Sara Louise had set aside the equivalent of $500.) We know that she spent a little bit of it on Jergens hand lotion, but we never hear what happened to the rest. I want to know that the money helped her somehow, even if it couldn’t help her achieve her childhood dream. I want her to acknowledge that saving the money just for herself—instead of turning it over to the household income—was worth it.

Both Caroline and Sara Louise work, every day and all through the summer. Sara Louise’s work pays off in cash from the crab haul. Caroline’s work pays off when Captain Wallace pays for her Baltimore education and, later, when she receives a full ride at Juilliard.

Studying music is work, which is something Sara Louise vaguely alludes to when she mentions that everyone in town took piano lessons but Caroline was the only one to get past “Country Gardens.” Of course, Caroline would have had more practice time than most, since the Bradshaw family has the only house with a piano and they charge the other kids 20 cents a week to use it.

But Sara Louise would have had just as much opportunity to practice as Caroline.

You can see, written right into Jacob Have I Loved, how both privilege and investment lead to increased income in the future. The teenage Caroline earns more than the teenage Sara Louise, if you count full ride scholarships as earnings—and this is exactly why many families want their kids to spend their summers studying or “resume-building” instead of getting jobs.

As adults, Caroline makes her “New Haven debut” in La Boheme (and it’s worth noting that she plays the privileged character, Musetta, instead of poor tubercular Mimi) and Sara Louise works her way through college on a partial scholarship and becomes a midwife in a rural mountain town. I’m guessing that even as an opera singer Caroline out-earns her twin, and the privilege and investment she started collecting in childhood will continue to pay off as she builds her career, maybe starts teaching, and so on. Sara Louise starts her career in a town where they’re as likely to give you a sack of potatoes as pay you (and you’ll be grateful for the potatoes, during the cold months when no trucks can get over the mountains).

Let’s go back to that “Sara Louise had just as much opportunity to practice as Caroline” thing. We know that Sara Louise is smart; when she finally takes her graduation exams (after quitting school to work, then studying at home) she gets the highest grades their town has ever recorded. We know she has a natural affinity for music, just like her sister, and even if her voice isn’t “as good” as Caroline’s that doesn’t mean Sara Louise couldn’t have found her own talent to invest in—and to accrue investments from adults—as a teenager.

But Sara Louise has two things going against her: she doesn’t have Caroline’s hustle, and she’s the daughter of parents who charge other kids 20 cents to play their piano. Her family is not wealthy, and Sara Louise admits that even that little bit of income helps, but they’re also stingy. They don’t see their children (or the town’s children) as resources to invest in. They’re happy enough when other people offer to give Caroline free voice lessons or pay for her to go to school in Baltimore. They do not seek out those opportunities for her or for Sara Louise. They might have cared if another kid stopped practicing their piano, simply because they would have lost out on 20 cents. They don’t care if Sara Louise stops practicing.

Near the end of the book, Captain Wallace tells Sara Louise that Caroline got everything she did because she “knew what she wanted:”

“Your sister knew what she wanted, so when the chance came, she could take it.”

I opened my mouth, but he waved me quiet. “You, Sara Louise. Don’t tell me no one ever gave you a chance. You don’t need anything given to you. You can make your own chances. But first you have to know what you’re after, my dear.”

But that’s a lot to put on a teenager who didn’t know, when she was nine years old, that playing the piano vs. playing outside would make a difference. You have to know what opportunities are available to you before you can go after them, and nobody talked to Sara Louise about what she could become when she grew up, and the work she might have to do to get there.

There weren’t even that many opportunities available to Sara Louise to begin with, not unless she chose to leave her hometown. At the beginning of the story she makes fun of the one girl who dreams of being a schoolteacher, and aside from that there aren’t a lot of career possibilities for women living on rural islands in the 1940s. Teenage Sara Louise works as a crab fisherman even though girls “aren’t supposed to,” and she brings in some of the biggest hauls the Bradshaws have ever seen, and Captain Wallace still lectures her on not knowing how to go after something.

Caroline, meanwhile, decides to become a musician. Music is one of those careers that nearly all children know is out there, even if they grow up in the smallest and poorest of towns. Music is something you can aspire towards.

You can read Sara Louise’s decision to hide $50 from her family when they need every penny, when they can no longer afford the cost of transporting Caroline to her free voice lessons, when their island is literally sinking into the water and Caroline is determinedly practicing in the living room as selfish.

You can also read it as self-preservation.

I want to know what she did with the money.

Next week: The Witch of Blackbird Pond.

Previously:

What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: Katherine Paterson’s ‘Bridge to Terabithia’

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments