Time and a Half at the Truck Stop

In May, a new rule updated the regulations determining who is entitled to the Fair Labor Standards Act’s minimum wage and overtime pay protections. I followed this with some interest. “The rule increases the salary threshold below which most white-collar, salaried workers are entitled to overtime from the current $455 per week (or $23,660 for a full-year worker) to $913 per week (or $47,476 for a full-year worker).”

Who Benefits from the New Overtime Rule

See, I received a crash course in overtime when I took on a summer job at the 24-Hour Trucker & Tourist Emporium,* a combination truck stop and gas station in a rural area off I-65. The 24-Hour T&T hired me as a 19-year-old cashier at the fuel desk, ringing up all the transactions for the truckers who were refueling on the diesel side. I quickly learned that I had responsibilities far beyond what appeared in the job description.

You see, a truck stop is a full-service enterprise. Most truck stops present themselves as a home away from home. Truckers work merciless hours, so when they have to fuel up, the truck stops are there to make the experience somewhat comfy. Where I worked, the truckers could take a shower, buy a few books-on-tape (this was pre-Audible), and eat something resembling a home-cooked meal, the quality of which varied depending on how long the food had been in the hot bar.

My swing shift started at 2:00pm and ran until 10:00pm. As soon as I donned my required orange smock, I started working the cash register, serving up chicken-and-two-sides boxes from the hot bar, and wiping down the showers after a trucker rented a stall. We usually had a custodian and a server during the day, but most evenings I ran a triangle from the cash register to the hot bar to the showers and back again.

It was exhausting. All I wanted to do at the end of a shift was soak my feet in Epsom salts, eat leftovers that weren’t from the T&T hot bar, and watch sitcom repeats.

Still, despite my wish for rest, 10:00pm meant more than quitting time. If I were lucky, a coworker might not show, and I would get a shot at working a second shift, which meant time-and-a-half.

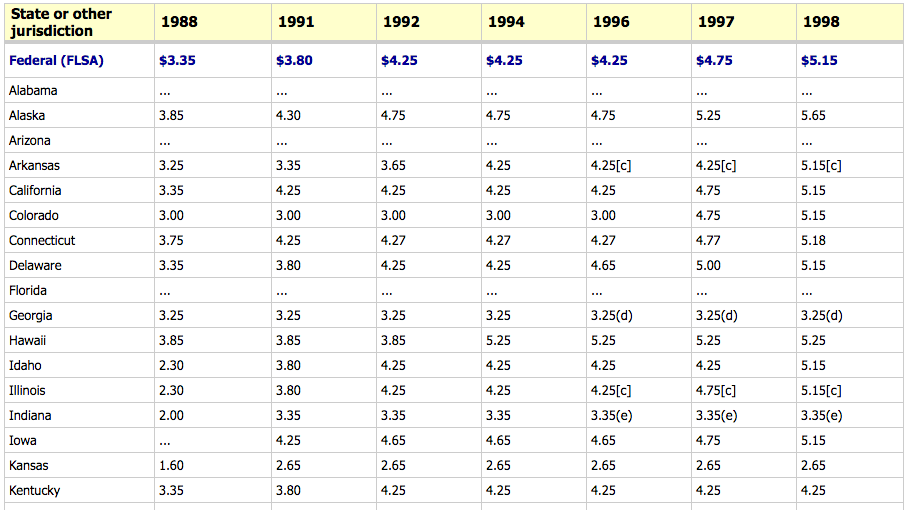

Time-and-a-half was the primary reason the truck stop was a plum summer gig. In the mid-90s, minimum wage was $4.25 an hour, but the truck stop paid a comparatively generous $6.00. Still, I needed that time and a half. The fancy college I was attending — let’s call it Highbrow University — gave me a generous scholarship that included tuition and board for a summer study program in London. My mom and dad reminded me, though, that the airfare and rail pass costs were not covered. Their own finances were precarious, and my sister was already looking at colleges. A summer job was a necessity if I wanted to cross the pond without breaking my bank account or that of my parents.

Once my boss figured out that I was one of the few employees brave enough to reboot the fuel desk computer, I didn’t have a problem picking up extra shifts. In fact, I hit a limit on how much overtime I could handle before the truck stop did.

Toward the end of the summer, the job wore on me. I lost it one night a few days after I had worked a double shift. As 10:00pm approached, I was counting the minutes until Danny, the aspiring assistant manager, was due to take over. He was usually on time, but I realized he hadn’t clocked in yet.

Kevin, the night manager, had already showed up. I asked him if he’d seen Danny. He said Danny was outside, but Danny wasn’t coming in because Danny was in a fight with his girlfriend and was considering going home.

I was not amused. “What does that have to do with me?” I looked at the clock. “Danny’s shift starts now.”

Kevin looked at the clock and then looked down. He was a manager, but confrontation was not his thing.

“Are you gonna get him or what?,” I asked, my voice clipped from anger.

“You might have to work for him,” Kevin said.

I spun around and started tending to the customers. As I was boxing up a 2-piece dark meat box with fried potato wedges and peas, the orange-and-yellow takeout box caught my eye. After I rang up everyone in the line, I grabbed the fried chicken box, popped it, tucked in the flaps, and scrawled the word “TIPS” on the top.

As new customers stepped up to the register, I announced that cashiers didn’t get tipped for working the hot bar, and my coworker had decided to stay home and wash his hair. A few of the truckers laughed. Kevin came over and asked, “What are you doing?”

“I’m going to London,” I said. “What are you doing?”

If Kevin answered, I didn’t hear him because a trucker wanted to chat about his own time in Scotland, and he told me to take a weekend trip to Edinburgh. After our chat concluded, the trucker put five dollars in the makeshift tip jar and was on his way.

Kevin eventually returned, with Danny slinking in behind him. At least one trucker hooted that Danny’s hair looked squeaky clean. As soon as Danny put on his smock and we swapped drawers, I balanced my register, clocked out, and was on my way. I kept the five dollars from the trucker. It was more of a symbolic victory, anyway.

At the end of the summer, I had saved enough to study in London. I couldn’t afford to travel quite as much as some of my peers, but I two trips to Edinburgh.

But my truck stop summer became more than a good story. Receiving overtime pay spoiled me for when I started working pink- and/or white-collar jobs. I couldn’t believe how much work was expected in return for zero overtime pay. (Truckers, for example, don’t get overtime.) If I had worked at the T&T eight hours a day for a full year, not including overtime, my pay would have been $12,480, well below the old threshold of $23,660.

Regardless of the nature of the work and the amount of overtime pay received, double shifts are hard — on the body and the brain. When most people volunteer to do extra, it’s not entirely out of the goodness of their own hearts. Sure, I didn’t want colleagues getting fired for love trouble or a sick kid, but I was also getting something out of it. And managers like Kevin got something out of it as well, since the truck stop stayed open and the regional office stayed happy.

We need overtime pay with a high threshold to serve as a buffer for life. For whatever reason, not everyone will be able to show up on time. Those who can take the shift get an incentive, and the business stays productive. Overtime laws may not have as much storytelling flair as a fried-chicken tip box, but I’d take good laws over my makeshift tip jar any day.

*All names changed, including that of the T&T because the company has been bought out and merged several times.

P.J. Morse is a cubicle jockey by day and a mystery author by night. She writes the Clancy Parker mysteries, whose heroine is a downwardly mobile guitarist for an indie band. Her upcoming series will revolve around the misadventures of a small-business owner.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments