I’m Afraid of Money

“I didn’t grow up with a lot of money, and we were evicted a couple times when I was a child. One time, I even came home from school and there was someone locking our doors. And he felt super guilty, and he asked me, ‘do you want to go in and grab some things?’ I always had this fear of being homeless. I decided to become an actor […] because I grew up without money, so I knew I could live without money. But I always had this thing of, I’m not going to be able to pay my rent.”

The above quote is from actress Jessica Chastain (in an interview with USA Today), and I envy her. I don’t envy her beauty or her career, except for her sex scene with Tom Hardy in Lawless. I envy her ability to be okay living without money so she could pursue her dream of one day pretending to have sex with Tom Hardy as a Virginia bootlegger.

I, too, grew up without a lot of money. More accurately, I grew up with the amount of money a single mother could generate to support a family of four. I am the youngest of three siblings and the only unplanned child. When I entered this world, my parents were already headed for divorce. My earliest memory is fighting with my brother in the basement while our parents fought upstairs in the kitchen. The sibling fight went a little something like this:

Me: “They’ve been fighting a long time. What are they fighting about?”

My brother: “Money. They always fight about money.”

Me: “Why are they fighting about money?”

My brother: “Because we don’t have any. We’re poor.”

Me: “Nuh-uh. We’re not poor.”

My brother: “Yes we are. We’re poor. Mom says so all the time.”

Me (getting upset): “We are not poor!”

My brother: “Yes we are!”

Me: “No, we’re not!”

My brother: “Let’s go ask them since you don’t think we’re poor!”

My fearless brother grabbed me by the arm and dragged me up the steps to the door leading to the kitchen. As we ascended the diamond-plated stairs we can hear the hostility, disgust and violence in our parents’ voices as they screamed at each other.

The doorknob in one hand and my arm in the other, my brother swung open the door, silencing the bitterly bickering couple.

“Are we poor?” he asked matter-of-factly.

“Yes!” they said in immediate unison. It seemed to be the only thing they agreed on.

My brother turned to me with a smirk, “Told you!” and we retreated to the basement as the marriage-ending fight continued.

I was three. My brother was five. Our oldest brother, who knew better and had remained in the basement, was seven.

Our parents were already separated at the time and finally divorced. Both only graduated high school. My mother was a secretary during the day and had two different waitressing jobs at night. My dad was a professional theater actor unable to pay child support. During the early years our electricity and heat were often shut off. Our church provided food, clothing, and Christmas presents. Sometimes we had a car, and sometimes we only had bicycles. I slept in my baby crib until I was six since we couldn’t afford a bed. Ashamed even now to admit that at the most desperate of times my brothers and I resorted to eating old dog food we were so hungry. (Our dog died after our dad left the house. He got out of the yard and was hit by a car. We kept the food because we missed Sampson (the dog) and our dad.) By the time I was seven, we were bankrupt and lost the house.

Over time our financial condition improved as my mother’s professional skill set grew and we became old enough to get jobs. When I was a teenager we lived in a two bedroom apartment, and I was acutely aware I was never going to wear Abercrombie & Fitch or Guess clothes. When I learned shopping at thrift stores was cooler than shopping at the mall, I thought people lost their minds. We shopped at thrift stores because we had to and others were shopping there because they wanted to?! Bananas.

I loathed not having enough money to have stuff or do things. I saw our lack of cash as shackles, and as soon as I was able to earn money, I wanted to be free. By age eleven I had a paper route and began stacking my tips in my bank account. It was my first job. I was hooked on making money.

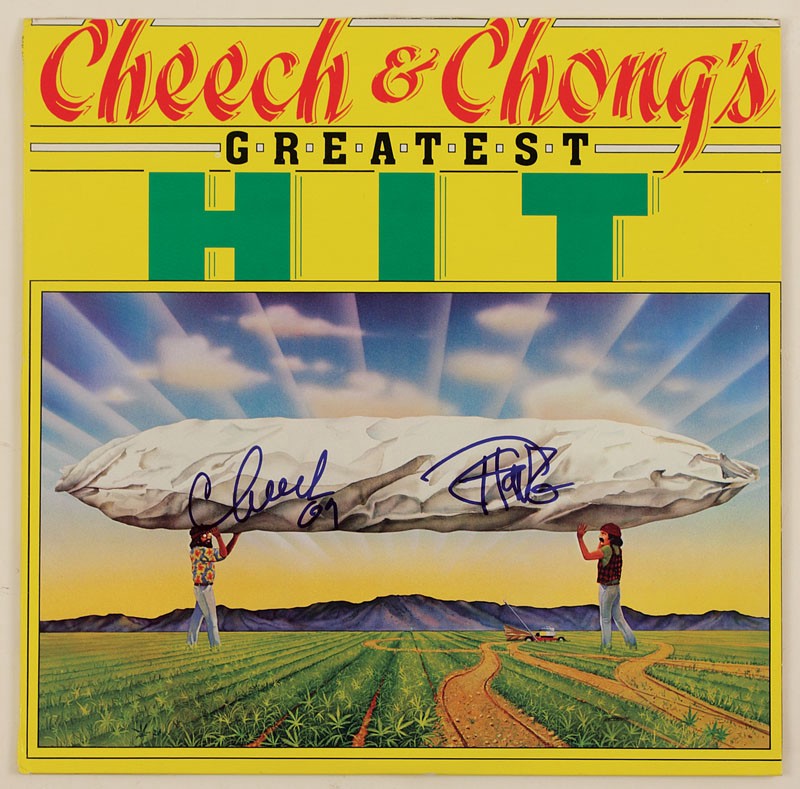

When my eighth grade class announced a trip to Canada and my mom spoke those all too familiar words, “We can’t afford it,” I ponied up the $400 of my own money. I felt like a princess walking the streets of Old Quebec City, touring the replica Notre Dame Cathedral and getting in free to a Montreal Expos game. I even bought Cheech & Chong’s Greatest Hit at FYE because I was the boss of myself, a savvy, international traveler beholden to n0 one. I was free.

In the coming years I paid for my own athletic gear, my first car (and the others after it), my beeper (holler 1996) and anything else I wanted plus could afford. In the immortal words of the Geto Boys, “Damn it feels good to be a gangsta.”

Yet poverty isn’t all that easy to escape. I was doing well, but not everyone in my family made it. My brother lost his scholarship to play football at a Division II school, and eventually his life, to drugs. My mother was diagnosed with Early On-set Dementia at 47. My brother was 26 when he died and my mother was 57. Both of them suffered a great deal in the last years of their lives. Both of them died terrible, tragic deaths.

At each downward turn of my loved ones, I pushed myself to avoid their fates. I conditioned my mind to stay the course, work hard, travel, get medical insurance, save money, be healthy. To do whatever it takes to not give up hope for a better life, which for most of my 30-ish years meant not being poor.

All financial things considered, I’ve arrived at that better life. But like Ms. Chastain I have dreams. Dreams that involve risking the financial solvency I’ve accrued over the last twenty-plus years working non-stop through middle school, high school, college, graduate school and now into my career. Risking a few thousand dollars here or there trying to make my dreams a reality feels like a dry mouth full of stale dog food. I simply cannot swallow it.

I’m still shackled by money; the memory of not having it and the fear of losing it now that I do have it. Living without money feels like gambling life or death. I’ve already both lost and won, and yet logically I know nothing good comes from continued anxiety over money. I know money comes and money goes. I know there is no reward without risk, but still here I am wishing about my dreams instead of doing something about them. I know I don’t want to be chained to three retirement accounts, a savings account and a good credit score, all of which can vanish from the next banking crisis or first severe illness. I know I haven’t buried my loved ones just to cower in the corner of mediocrity holding onto healthy bank statements for dear life with a broken heart, an unhappy mind and an unfulfilled soul.

I know there is more to living than simply not being poor.

With money in the bank and every possibility ahead of me, my hope for a better life now lies in the actualization of my dreams. If I ever want to end up in bed pretending to make love to a surly turn-of-the-twentieth century Tom Hardy while listening to Blind Melon Chitlin after watching Office Space, I need to be okay living without money.

Rachel Joyce is a digital strategist working to make the internet better for you and me. She’s also a reformed food blogger and currently in the top 20% of New York City-based Trip Advisor reviewers.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments