I Got Audited by the IRS (and Lived to Tell the Tale)

I felt as if a thousand-pound weight had descended on my chest.

I have exactly one thing in common with Donald Trump: I’ve been audited by the IRS.

On a nice spring day in late April of 2012, I received an envelope from the IRS. Since it was after tax day and I’d filed my return early in any case, I presumed it would be a nice letter saying that I would get a little bit back from Uncle Sam this year, just like I had in previous years.

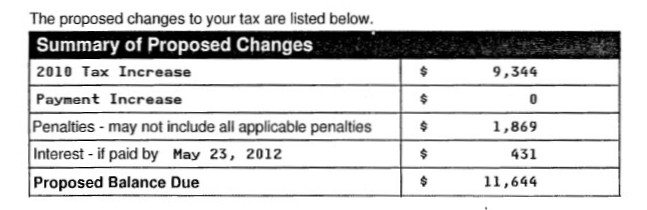

I opened the envelope and saw in big block letters on the top of the page, “CP2000.” This meant nothing to me, though I was sure that I did not know the universe of forms available to the IRS. Neither was I able to decipher the 12 lines of alphanumeric identifiers that followed, except for my own name and SSN. I did see that for the first time ever, the return address was not a generic PO Box in San Francisco, but the “Office of M Atwell.” And finally, I got to the meat of the document:

In short, I had allegedly made a mistake on my tax return two years ago, to the tune of $9,000 in back taxes and a few thousand more in penalties and interest. And although it had taken one of the country’s largest employers of accountants two years to double-check my return, I had just thirty days to respond.

If I still had my all my documents, of course. If I felt like I had the expertise to pore through the five supplemental pages of the CP2000 . And if I wanted to run the risk of facing even more penalties and interest if my response was rejected.

I felt as if a thousand-pound weight had descended on my chest. I had difficulty breathing; I felt nauseated. Kind of like I had failed a hundred math tests all at once. Except this time, there were painfully real and painfully expensive consequences.

Although I was in the mail room of my apartment building — a reasonably busy public place — I had to sit down on the ground for a few minutes and gather myself.

One of my neighbors, who always walked his dogs around the same time that I got home every day, asked if I was feeling all right.

“I’m being audited by the IRS,” I said, by way of answering his question.

In the grand scheme of things, my situation was not so bad. Although I had fallen into the unlucky one percent of taxpayers who get audited every year, I “lucked” into an audit by mail. I did not have to go to an IRS office, or worse, have an auditor come to my apartment to personally check on my records.

Still, that was cold comfort, and I walked up to my apartment, my eyes near tears. I’d filed on my own, not even using tax preparation software. I’d moved twice since I filed that return, and wasn’t even sure if I kept my old forms. Most of all, I was still so shaken by the fact that I might owe over $12,000 that I couldn’t focus on the rest of the CP2000, which (as you might expect) was a dense series of tables that itemized every possible mistake I’d made on my 2010 return, and summarized them in a few dire sentences.

I called my girlfriend at the time, and I called my parents. And after they calmed me down, they told me in no uncertain terms that I needed to do what I should have done a long time ago: get help.

This election season, like every other one, we’ve heard about how complicated the tax code is, and how it needs to be simplified. And there’s something to that: the code runs about 2,700 pages, or the length of the entire Harry Potter series.

But when you’re young, naïve, and/or in a low tax bracket, you don’t have much to worry about. You just fill out a couple dozen boxes on your 1040EZ, and even if you make a mistake you are pretty unlikely to hear about it. At most, you get a different-sized refund check than you were expecting.

This is how bad habits form.

The first time I did my taxes, I was a freshman in college. I got a work-study job in the school library that extended through the summer, and brought in a total of about $6,000 that year. With no trust fund and no real savings account to speak of — all that money went out the door in summer rent, books, and late-night pizza runs — I had one form to wait on, and one form to fill out. About the most complicated thing I had to figure out was if my parents were claiming me as a dependent.

My situation didn’t really change during college, so I got into an easy routine. February: get W2. March: send 1040EZ. April: cash refund.

After college, I got a teaching job that paid about $18,000 a year. Not much to write home about, but it was a living wage. More importantly, it didn’t complicate my tax situation too much. I was able to save a few hundred dollars a year, so the 1099-INT it generated doubled my tax form collection each year.

Then, I joined the corporate world. And that was when things went off track.

In 2010, I left Indiana and moved back to my hometown of Seattle. There, I got a job at Amazon.com. This was a big change in my financial picture. Most obviously, it paid about double what I made as a teacher. Also, like many tech companies, Amazon compensates its full-time corporate employees with restricted stock units in addition to cash. (Disclosure: I still own shares in Amazon).

Now, in almost all respects, this was great for me. I could finally take all the personal finance advice that was just a dream when I was on a teacher’s salary. I contributed to an IRA! I increased my credit card limit! I bought some index funds! I even gambled on some risky individual stocks!

What I did not do, however, was pay close attention to what that meant for my taxes. And when January 2011 rolled around and I picked up the old 1040EZ form from the library, I figured this would be like every other year. That is to say, I did not really read the instruction booklet, except to check whether I had hit the income cutoff for using the 1040EZ, which I did not.

So I filled it out as usual. Along the way, I noticed that things didn’t quite match up. I didn’t know exactly where to put the money that I inevitably lost on my risky stock picks, or how to account for the RSU numbers. Where there was ambiguity, I simply picked what I felt to be the closest option. I think most of it got fudged into ordinary income, though I’m sure some if was sprinkled in the other few boxes as well. But I didn’t worry: I hadn’t thought too hard about my taxes thus far. Why start now?

And failing to read the rulebook qualifies as, in IRS parlance, “negligence or disregard of rules or regulations” done in a “careless, reckless, or intentional” manner.

This was bad, though not tax fraud-bad. But it did cost me.

I took the advice of my parents and my girlfriend and got help. I found the highest-rated accountant in my neighborhood, literally ran over to their office, and explained to a mildly bemused CPA why I was on the verge of a tax-related nervous breakdown.

After we got the general terms of our agreement out — no, I had not willfully deceived the IRS and yes, I was prepared to pay his $200/hour fee — he said that this would probably be a straightforward case and I should start getting the paperwork together right away.

“You do have all your paperwork still, right? You’re supposed to keep all documents for a minimum of three years,” he said, looking at me over the top of his reading glasses.

“I…think so?” I replied.

He raised an eyebrow.

“I’ll find everything,” I said, and hurried back home to do a lot of digging.

In the end, my new best friend the CPA was right: It was a straightforward case. Mostly, my flailing attempt to make everything fit into the 1040EZ had done me no favors. On the one hand, I had claimed as ordinary income things like stock purchases (which are taxed entirely differently than salary and wages) and RSU awards (which did not vest until years later, at which point they became taxable). On the other hand, even though I was making tax-deductible contributions to my IRA, there isn’t a place on the 1040EZ to report those contributions — so I was effectively not reporting a big source of deductions.

In short, I was indeed misreporting my tax situation to the IRS in 2010, though this was mostly due to sheer stupidity rather than massive fraud. And thankfully, although I didn’t have paper copies of many of my tax documents from 2010 anymore thanks to my two moves, I was able to download digital versions thanks to the miracle of online banking.

So I ended up paying about $500 in back taxes, another $250 in penalty fees and interest, and $200 to my CPA for the hour that it took him to rectify the situation. And I only have to endure the minor shame of filling out a tax form badly, rather than the relatively more major shame of having been on the receiving end of a justified IRS audit.

I also stopped doing my own taxes that year and have used a local CPA ever since. I have no hope of ever approaching expertise in the realm of taxes, nor do I have much desire. As I learned, being on the business end of an audit is extraordinarily unpleasant — psychologically and financially. I’d rather pay a relatively small amount of money to avoid a potentially gigantic penalty. And if (God forbid) it ever happens to me again, I feel better knowing that I have someone to get between me and the IRS if I need them to.

OK, so I guess that means I have two things in common with Donald Trump. But that’s all, I swear.

Darryl Campbell is a former medieval archaeologist and Jeopardy! contestant. He lives in Dallas, and tweets at @djcampb.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments