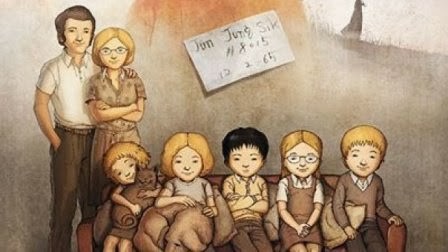

Another Perspective on Crowdfunding Adoption

When we had our crowdfunding discussion last week (parts one and two), some of our commenters expressed extreme reservation at the idea of crowdfunding an adoption.

The Toast’s Nicole S. Chung shares a similar perspective in her essay “Why the Trend of Adoption Crowdfunding Makes Me So Uncomfortable:”

In our culture, people seem to buy into the notion that if you can afford to pay for something, it should be yours. You can give a child a comfortable life, support and send them to college, and someone else can’t? You should definitely have a kid. Crowdfunding campaigns ask donors to endorse parenthood for people they might not even know, and to do so with their money — the very thing that many people think is what makes one a responsible, “worthy” parent in the first place.

More importantly, adoption crowdfunding often perpetuates an overly simplistic narrative about the adoptive process:

Adoption crowdfunding campaigns can (even unintentionally) promote the belief that adoptive parents — due to location, wealth, religion, race, nationality, marital status, privilege, or any other combination of factors — are superior to birth families. Of course there are many reasons why someone might make an absolutely wonderful adoptive parent. But the reason often touted for adoption, the reason some people feel okay asking their friends and people they don’t know to help finance it, is the general promise that adoption gives a child “a better life.”

Donating to a private adoption fundraiser might appeal to you for this reason, even if you don’t know the hopeful parents yourself. “A better life” sounds like an unassailable goal. Still, it’s worthwhile to consider that word, better, and how loaded it really is. Better than what? Better than the life their families or communities or countries and cultures of origin could have offered them. Better, because comparatively well-off and overwhelmingly white Americans can provide a child with anything — at least, everything that’s truly valuable, truly important.

So focused are we on this notion of better that we gloss over any losses, any biological relatives children might have remaining, and barely give a thought to the communities from which they are adopted. If original families are mentioned approvingly in this narrative, it’s usually just to applaud their sacrifice. There’s a connection many people still make, sometimes unconsciously, between worthy parents and wealthy ones.

It’s worth reading the whole essay. It’s also worth noting that Chung doesn’t necessarily think it’s the crowdfunding part that’s the problem:

I’ve explained why, as an adopted person, adoption fundraisers give me a shifty, sinking feeling when I see them pop up in my social feeds. I don’t believe they represent the greatest challenge in adoption. I don’t think it’s necessarily terrible to donate to one. I don’t think we need to spearhead a campaign to eliminate them. What we do need is a lot more education and nuanced discussion about adoption, who it is supposed to benefit, and how it might need to change. We need to skip the easy platitudes and consider the institution in all its complexity — that’s something everyone deserves if we are going to be asked to give our money to support individual private adoptions.

Take a minute to read Chung’s essay, and let us know if you agree.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments