The Love of Objects

by Luke Geddes

I am an unapologetic buyer of goods — and not just any goods but those that to most eyes are more material than experiential. Even worse, I collect them.

I collect old toys: Marx figures, Aurora monster models, Soaky shampoo bottles shaped like cartoon characters, pull toys, blow mold coin banks, squeeze toys, board games, paper dolls etc. They don’t “do” much. At best they’re decoration and at worst they languish unseen in storage until I find a suitable display for them. Even the board games go generally unplayed. (Gidget Fortune Teller and the unimaginatively named Patty Duke Game are not as thrilling as one might hope.)

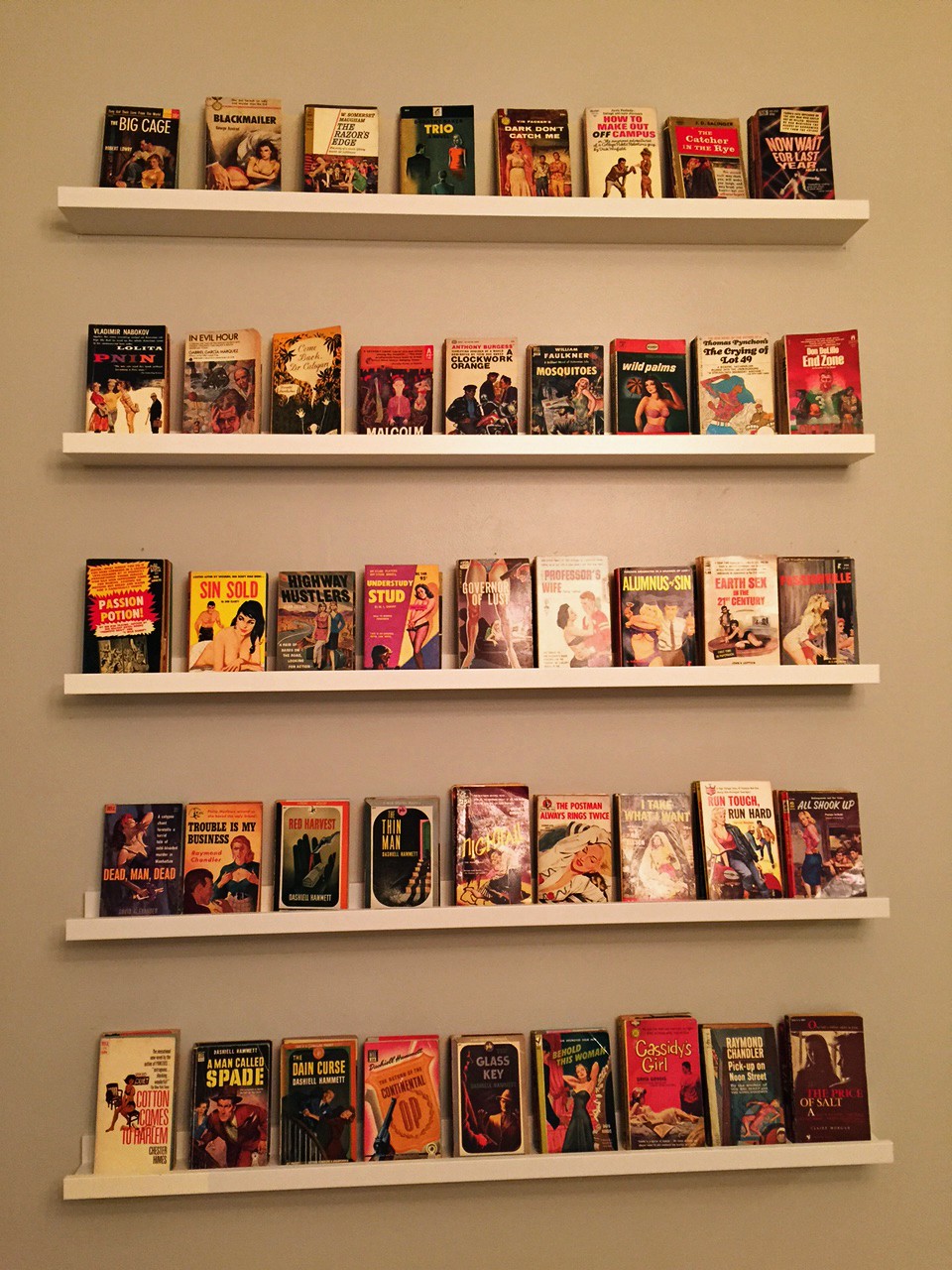

I collect pulp novels and paper ephemera related to mid-twentieth century teen culture and rock ’n’ roll. Magazines might be browsed now and again, may be displayed on the book rack in my office, but they mostly go unread. I do read a lot of the novels, or at least plan to get around to reading them. But when I’m not reading them they don’t “do” much, other than just sit there on a bookshelf or proudly on display on my home’s “wall of pulp.”

I have a small collection of vintage Halloween decorations: tin noisemakers, hangable cardboard cutouts, orange-and-black plastic candy containers, and other stuff that gets taken out and put up on walls and atop shelves each October but doesn’t otherwise “do” anything but look cool for one month per year.

I collect vinyl records. When they’re not being played — and I can only play one at a time and only play so many in an hour or a day — they don’t “do” much; they sit there snugly in IKEA Kallax shelves waiting to be played and taking up space — arguably unnecessarily, as there are only a few rarities in the collection that cannot be found for free via Spotify or YouTube.

The money I’ve spent on my collections, I’m told, could have gone toward scientifically proven happiness-increasing, memory-creating experiences such as a dinner out with friends, a culturally-enriching vacation to important historical sites, or, I don’t know, skydiving or karate lessons. Instead I squandered it on things, and not just things but a needless accumulation of things.

But buying and owning these things brings me pleasure, the type that can be hard to explain or justify. Collecting is basically irrational. There’s no logical reason I choose to collect these particular things. Snuff bottles, art pottery, Pez dispensers, cassette tapes, Beanie Babies, or any number of so-called collectables would have about the same function: continual existence, but, at best, only occasional use.

A collector’s zeal for an object is irrational, but ineluctable. Evan Connell’s 1974 novel The Connoisseur offers us an object lesson in loving objects. It tells the story of a milquetoast insurance executive named Muhlbach who on a business trip to New Mexico becomes enamored with a pre-Columbian terracotta figurine: “I want this arrogant little personage, he thinks with sudden passion. But why? Does he remind me of myself? Or is there something universal in his attitude? Well, it doesn’t matter. He’s coming home with me.” With this first purchase a collection, and a collector, is born.

Of course, Muhlbach’s interest in pre-Columbian artifacts eventually culminates into a monomaniacal obsession that alienates him from his children and his girlfriend, damages his career, and sends him on a path to financial self-destruction.

I admit that there can be something unhealthy about collecting. At specialized conventions devoted to pulp literature, comic books, and vintage toys I often see joyless middle-aged men rushing from table to table with a checklist in hand, desperate to snag their imagined ideal collections’ missing pieces. I’m proud of my collection, but also a little embarrassed whenever a stranger or plumber or handyman comes over. “The broken dishwasher” I tell them, “is just past the ample visual proof of my profligacy and childish tastes.”

Collecting is too often mistakenly conflated with hoarding. More accurately, it’s curation. The pieces in my collections pass the Kondo test, I assure you. Meanwhile most books I read I get from the library or sell back when I’m finished with them. (I only keep vintage editions, or those with particularly cool covers.) I’m selective with the clothes I purchase. I’ve pared down DVDs and other media, trashing the packaging and keeping the discs tightly filed in storage boxes. I like old things, used things. I could flatter myself by saying they’re recycled. If something is new, mass produced, common, and not frequently used, I don’t need to keep it.

None of the objects in my collections are one-of-a-kind, but they are of varying scarcity and, to my eyes, unique albeit often kitschy. Many are things I never would have known they existed if I hadn’t stumbled across them by chance at flea markets or antique malls or vintage shops. Some can’t even be found on an endless internet marketplace like eBay, even if you knew to look for it. Like this orange mouse thing, what is it even:

There’s experiential value to shopping for such specialized stuff. Many collectors go to conventions for the community or shop flea markets largely to converse with fellow collectors and dealers. There’s also a genuine thrill to getting a good deal or discovering some long sought-after item you’d never thought you’d find that imbues a given object with extra joy, like the other day when I found a first pressing of Lee Hazlewoodism: Its Cause and Cure for only six bucks.

Sometimes when I go out to eat I look at the bill and think regretfully about the money spent, how it could have gone to physical objects I could hold and keep and own rather than a merely transitory meal. This falafel could have paid for six records from the dollar crates at Everybody’s Records (one of my favorite local haunts), I think. I’m not delusional enough to believe that my baubles constitute a sound investment, but it is nice to know that my collections are worth something, even if much of it is of such esoteric interest I doubt I’d break even if I decided to purge it all.

But resale value has no bearing on my collecting. I collect for the love of the object.

This story is part of a series examining our financial vices.

Luke Geddes lives in a house full of stuff in Cincinnati. He will co-edit the soon-to-be launched The Flyover, a blog about cities that aren’t New York.

Photos by the author

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments