Do The Side Hustle

There’s an interesting post on Chelsea Fagan’s blog The Financial Diet about “side hustles” and the way we can feel ashamed of earning money by doing X when what we really want is to identify ourselves as successful professional practitioners of Y. For example, well before Fagan earned a sufficient income by writing, she called herself a writer.

I wasn’t really doing this obfuscating out of an opportunistic desire to squeeze the most money out of my writing jobs. I was mostly doing it because I was embarrassed, ashamed to have to supplement what I considered to be my “real” job with side work that never felt like something I “should” have been doing. Despite never being a particularly hard worker before I became a writer, I certainly wanted to project an image of hard-won success. I never liked admitting to people that I was at community college, or that I always had multiple, low-paying jobs, or that I was going to France for school, but also to work as a nanny to pay the bills. I didn’t think I was above these jobs, really, so much as I felt constantly fearful of the judgment and stigma that went along with them. Even at low-paying jobs I actually, genuinely enjoyed in the moment, the perception of me that went along with it stung. And it stung all the more so when it seemed to get in the way of my “real” career, when it was the thing standing between me and full-time artistry, if you could call it that.

I appreciate her honesty, though I think she could go a step further and admit she did kind of feel as though those other jobs were beneath her. That’s why we obfuscate, not merely because we want to project an image of who we wish we were but because we are a little bit ashamed at not yet being where we want to go, working more menial jobs alongside folks with fewer credentials. The wriggly shame of having to do something for which we may be technically overqualified — followed by the even wrigglier liberal guilt — is natural, maybe, because dissatisfaction keeps us striving; but it’s not necessary.

The same way I wish we could be a little more transparent about where our money & privilege comes from, I wish we could admit that we don’t have it together quite yet, that many of us are still cobbling together gigs — baby sitting, Lyft driving, apartment painting, what have you — and side hustling our way through life. That doesn’t mean we’re failures. It means we’re resourceful.It wasn’t that long ago that I was a frustrated receptionist, working ten hour days answering phones, smiling at strangers, and trying to be patient as messengers flirted with me. (“You must work out!” “Nope.”) Over the years, I’ve paid the rent however I could, drawing the line at writing other people’s graduate school applications only after I tried and hated it. Hell, even Mike cat sits!

It is very hard to get paid a living wage to do the thing you love, full-time. How many people do you know who have summited that particular mountain? Most of us are down here, at base camp or lower, climbing, or planning to climb, or saying, “Fuck it, this isn’t worth it, I’m going back to school to be a CPA.”

Fagan has made peace with the face that her life is a knit-together crazy quilt of side hustles. Now that the hustles are at least passion-related, she even likes it that way.

I do 60–75 pieces of writing per month, ranging from a few hundred words of advertising copy to several thousand for a niche publication. I write recipes and lists and essays and compilations, and though I don’t take every job that comes my way, I take a lot of them. I’m not yet at a position, financially, where I can cherry pick the work I do, or dedicate 100 percent of my time to my site. (Right now, it’s about 75, which is already huge.) But I have “side jobs,” they’re simply more prestigious than they once were, relatively speaking.

I no longer feel the stigma of talking about them, either. Part of this is because even a non-cool writing job is still a gift, in many ways, and part of it is because I give less of a shit what other people think.

Even a non-cool writing job is still a gift. Yes, exactly.

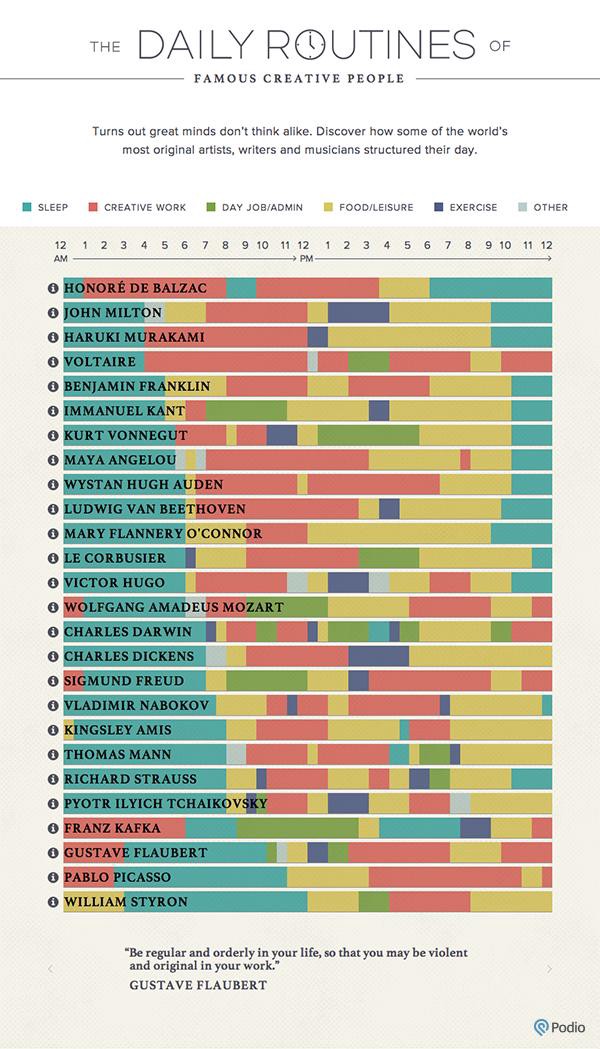

I’m reminded of this infographic (on GalleyCat, via Podio) of how famous creative people through history have spent their time. These are people at the tops of their fields, most of them very privileged white men with servants. Yet even some of them — Kant for example, and Vonnegut — spent less time on creative work than they did on admin/day jobs.

A comparable chart of creative people in the 20th and 21st centuries would be, I’d wager, far greener with day jobs and side hustles. That’s not necessarily a bad thing, either. An article in Slate points out,

having too much to do is also an unbeatable motivator. If you can truly only spare a couple hours a day for a particular task, it is amazing how much you can get done in those hours. As Nicholson Baker told me — referring to a time in his life when he was writing and running a nonprofit at the same time — “You find out a way to get more done when you’re really busy. You just learn how to fit it in.”

As novelist Martha Maretich writes:

I myself have always had a day job. I wrote my most recent novel, The Merchants of Light, while covering innovations in the field of social finance — with some nonfiction, like this BOOM! essay on sustainability in California, social media and editing work on the side. This leads to the sort of schizophrenic LinkedIn profile that confuses some people (though never other artists) and yet makes for an interesting professional life. The fact is I’ve always valued my day job, so much so that maybe it doesn’t really count as a day job. Reading into the statistics, this means I’m much luckier than most writers today.

I also love the way this poet-cum-lawyer in the Atlantic — who tried bar tending and various other side hustles first before settling down to be an attorney — describes her current situation.

I think whenever you have to perform a couple of different identities within your life, each is affected by the other in some way. My job provides a nice counter-balance to the anything-goes world of poems — it’s still a persuasion-based job, but definitely in a rational, intellectual, responsible, real-world sort of way. This may sound terrible, but in my day job, I have to be a good person — and don’t get me wrong: I want to be and like being a good person, but poems give me a path to wrestle with the terrifying, difficult, absurd, imperfect, uncontrollable parts of the world in a much different but incredibly important way. As an attorney and a policy advocate, I can focus on actual change for the better. In poems, I can kind of tear a hole in that continuum and play around more with the scaffolding of it all.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments