The Playing Field Isn’t Level But That Doesn’t Mean Don’t Play

How honest is too honest, when it comes to money? This weekend, author Ann Bauer caused a digital snowicane with a piece in Salon called “Sponsored” By My Husband: Why It’s A Problem That Writers Never Talk About Where Their Money Comes From.

I attended a packed reading (I’m talking 300+ people) about a year and a half ago. The author was very well-known, a magnificent nonfictionist who has, deservedly, won several big awards. He also happens to be the heir to a mammoth fortune. Mega-millions. In other words he’s a man who has never had to work one job, much less two. He has several children; I know, because they were at the reading with him, all lined up. I heard someone say they were all traveling with him, plus two nannies, on his worldwide tour.

None of this takes away from his brilliance. Yet, when an audience member — young, wide-eyed, clearly not clued in — rose to ask him how he’d managed to spend 10 years writing his current masterpiece — What had he done to sustain himself and his family during that time? — he told her in a serious tone that it had been tough but he’d written a number of magazine articles to get by. I heard a titter pass through the half of the audience that knew the truth. But the author, impassive, moved on and left this woman thinking he’d supported his Manhattan life for a decade with a handful of pieces in the Nation and Salon. …

In my opinion, we do an enormous “let them eat cake” disservice to our community when we obfuscate the circumstances that help us write, publish and in some way succeed. I can’t claim the wealth of the first author (not even close); nor do I have the connections of the second. I don’t have their fame either. But I do have a huge advantage over the writer who is living paycheck to paycheck, or lonely and isolated, or dealing with a medical condition, or working a full-time job.

Reactions ranged from “At last!” to “WTF?”

Speaking for the former, a commenter on the original post wrote:

Thanks for this concise view into this issue. While there are numerous other factors in any given writer’s success (or lack thereof) — relative talent and hard work among them — it has become increasingly obvious that wealth and connections are often-unacknowledged factors in writers’ careers. That doesn’t mean that we have to belittle the sometimes genuine accomplishments of well-supported writers. Nor does it mean that writers that start without these privileges never make it big. But acknowledging the full range of factors allows for fuller understanding and that can only be a good thing.

A couple of years ago I did an analysis of the New Yorker’s 20 Under 40 for a blog I was writing at the time, and I found this same pattern in evidence there. But what struck me even more than the pattern itself was the attempt to hide it in many author bios.

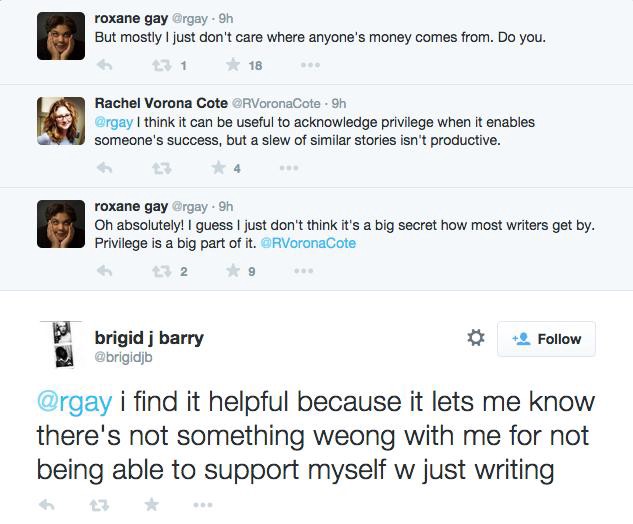

Some people on Twitter wondered whether the whole thing was TMI.

And Billfold pal Alexander Chee replied, “I wish Bauer’s essay had examined more of what was going on for her when she was struggling, and how she got her way to where she is now. Instead, we move quickly past what seem like significant events and arrive at a j’accuse moment with two other writers. ‘Marry well’ isn’t exactly advice on how to live as a writer. But that ends up being her takeaway. I do think writers need to marry people who are supportive of them, whether or not those people support them in the other way. But we don’t get much on that topic either.”

He pointed to an interesting, similarly candid counterpoint essay by novelist Susan Straight, who has managed to write no matter what:

I joked all the time about writing in my car, about never having been to a writers colony but having finished my third and fourth novels in cheap motels where I stayed awake all night because in the first, someone was trying to kill his wife and she beat him up and he lay in the hallway moaning; in the second, two men were making drug deals all night long in the hallway; and finishing my fifth novel at Riverside’s elegant Mission Inn, in 1995, because I felt the weight of Erle Stanley Gardner and the other writers who’d inhabited the lovely room where I wrote — by hand — feeling like a fraud.

And sometimes other writers would say to me, “Well, it’s easy for you to write anywhere, I mean, I couldn’t do it, I have to have utter silence, and concentration, and I’m working on different kinds of themes, I mean, my work is very serious.” Yep. People said that. I was writing then about a woman killed in an alley, because of jealousy and unrequited love, and during that time, a cousin’s daughter was killed in her home, because of defiance and unrequited love. It felt serious to me. I wrote about working class characters in Southern California, and often writers not from California would add, “I mean, it’s sunny outside, and you guys just live in your cars, right?

In a way, it can be easier to be frank about trials and tribulations than to acknowledge privilege. Everyone has to deal with obstacles, after all, so most everyone can relate to / empathize with struggle; whereas we don’t all get trust funds or rich, supportive partners. Those are distributed inequitably. But so, for that matter, are health, beauty, and talent.

We can’t control who gets dealt more luck in life. To a degree, we can’t even control who gets more resilience. (There seems to be a genetic component there.) What we can control is how hard we work and what priorities we set for ourselves, regardless of our field. Focus doesn’t guarantee success in writing or art or business or life; it is usually a prereq, though. Necessary, but not sufficient.

Some of the greatest and most notable writers in recently history from James Baldwin to Cheryl Strayed — including Charles Dickens, George Orwell, Stephen King, Sandra Cisneros, and JK Rowling — had very little going for them besides talent and focus. Though they had to scramble their way up a mountain while other authors got to ride the chair lift, they still reached the peak.

To me, the most interesting revelation from the piece and the ripples it has caused is the divide between people who don’t want to know or don’t care where other people’s funding comes from and those who do. I’m fascinated by financial realities, but then, I write about them all day long.

ETA: Hot take by Flavorwire’s Sarah Seltzer:

why should we pit ourselves against each other? Without a doubt, time to create and dream is the “room of one’s own” of the 21st century. And there’s a sacred myth of pursuing any art form, that contains some truths in a time-strapped world: You do have to give something up, or cut back. Sometimes it’s a career of your own, or financial independence vis-a-vis your life partner, or sleep, or time with family and friends. Sometimes it’s stability, sometimes it’s the inspiration that comes from instability. So yes, an artistic pursuit works well when there’s someone else near you filling in the gaps of whatever it is you give up, as sort of mini collective enterprise of two. …

We (particularly women) can’t have it all. Instead of talking about how we help everyone get by and pursue their passions in addition to career and family ambitions, it inevitably becomes a fraught discussion about individual choices, and judging each others’ choices.

What I’m saying is: I don’t want the important writing and money discussion to become a new version of the Mommy Wars.

Hear, hear.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments