Can’t Take It With You #3: Cecily Hintzen, Memorial Planner

by Rachael Maddux

Cecily Hintzen is in her 50s, an age where many start casting longing glances at the idea of retirement. But earlier this year she left the job she’d held for a decade, at a hospital pathology lab, and started her own business, Pathfinders Memorial Planning. Her new gig is twofold: She guides grieving families in organizing loved ones’ memorial services (doing as much as full-on event planning, or as little as producing remembrance slideshows) and she works with not-dead-yet people to make their own end-of-life wishes known before it’s too late.

In the few months Hintzen’s shop has been up and running, most of her clients have been the former rather than the latter, something she hopes will change over time — but she knows very well how tough it can be to get people to plan for (or even just talk about) their own eventual death when it’s (probably/hopefully) many years away.

I spoke with Hintzen in early May, and I had some fresh personal experience that made me especially appreciative of her work. My grandfather died in late April, and at the time of our interview I was witnessing my mom and her brothers planning his memorial service. He’d made his final wishes known, right down to a poem he wanted included in his memorial. This made a hard time a bit easier, but it was still hard — emotionally and logistically. I can’t imagine what it would have been like if it was just like, “Welp, he’s gone and we have no clue what he would have wanted.”

If you live in the Santa Barbara, California area and need help planning a memorial service or doing your own end-of-life planning, she may be your gal. For everyone else, find your town’s own Cecily Hintzen equivalent, or do it yourself (the National Institute on Aging has some good resources). It might be hard and weird, but you’ll probably feel more than a small bit of relief. And one day — hopefully years and years and years from now — your family will be grateful that you did it. Unless they’re all heartless cyborgs. In which case, oof, good thing you’re dead.

So I was interested in talking to you because you’re making a career change, and also because of the realm that you’re working in.

For me, the career change, it’s one of those things — I think most of us really want to do work that matters and makes a difference. You want to leave the world a better place than you found it. And before I was doing this job — which I’ve been doing for the last 10 years, working with a local hospital in various roles — I was a high school counselor. That had its own challenges, but at least I felt that I was meeting the needs of an underserved population. I got all of the “I think I wanna kill myself,” “I’m pregnant, I don’t know who the father is,” “My parents are beating me.” After a few years of that, it wears on you and you begin to wonder, “Well, gee, I really want to make a difference, but did I really?” That’s why I left that job. I was getting older and I thought, “I really need to find a job that has good benefits and that I can retire from.” So this job at the hospital served that purpose, until recently. I just really felt like I couldn’t continue doing that. I felt like I was marking off the days until I either died or retired.

So I put my feelers out everywhere, and I landed at this organization called Women’s Economic Ventures [WEV]. They basically said, “What do you think you’re really good at?” And I said, “Well, I’m really good at figuring out what people want and how to make that happen.” I have skills that most people don’t — I’m not an artist or anything, but I have really good organizational and computer skills. I thought of a whole bunch of different things I could do — I could be a virtual assistant, I could do this or that. Well, the thing that gave me the most joy and made me feel the most fulfilled was something I’d never been paid for before, and that was working with people who had approached me when they were faced with dealing with someone’s sudden death in their family.

My sister lost her son, who was 25, and I was her first phone call. I came in and — being bossy big sister, but helpfully — said, “OK, here’s what we need to do.” I was just so upset with the lack of communication. It was a coroner’s case, and the coroner and the law enforcement were very uncommunicative. They were really vague about when things would be completed and when they could actually have the body and who it’d be sent to and all this stuff. At the time I didn’t really know anything, but I knew that having a funeral was expensive and my sister’s family didn’t have a lot of money. So I went with them to the mortuary and was very disappointed at the sort of businesslike, everyday, perfunctory, “Yeah, OK, you’re client 4551. Here’s the form. What do you want?” I started saying, “You don’t have to make that decision right now. You don’t want to pay for a casket. Ask for the cheapest casket because it’s going to be burned” — stuff like that. I thought, “There’s gotta be a better way, a more personal way of dealing with this.”

So I had that in my mind. And in the meantime some other people would come to me with their losses and say, “Can you help me?” or “Can you help organize a memorial?” and I would do it. So that’s what my gift is — it’s helping people do something that is easy for me to do but hard for them. It really makes a difference to them.

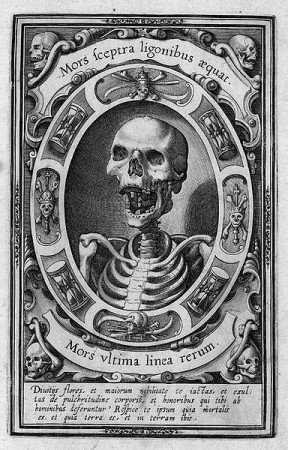

And the more I got involved in it, I started thinking about how we keep death behind closed doors. We never talk about it. It’s something to be afraid of. So I developed my business plan around creating memorials for people that were meaningful, in a way that wouldn’t cost them a lot of money. My primary goal is to provide them with a way to honor their loved one in a way that is meaningful and healing, not only for them but all who attended.

I’m really brand, brand new — just launching it now. But I’ve already connected with the most awesome group of people who really want to change the culture surrounding death so that it’s something we accept as part of life, so that we support one another while we’re dying and support the families of those who are dying as much as we would when someone’s born. When someone’s born, everyone’s there — they want to see the cute little baby and all of that. But when people are dying, a lot of people die alone. And the families are sort of forgotten after the memorial. I really feel like it’s tied to community, that we’ve lost our sense of community in that way. Everything’s in these little pods — it’s not that easy to have a community anymore.

Or if you do have a community, it may be more the group of people you’ve selected to keep up with on Facebook — they’re not necessarily physically present in your life.

That’s true. I think there is value in the online community, absolutely. There’s a lot of support where there would otherwise be silence, when people are going through things. Some people use that when they’re going through a hard time to get support from their friends, because it’s easy for them to interact online when they’re hundreds of miles away. That’s great, but that doesn’t really help with the immediate needs of, “I have to do this now, I have to figure out where my mom’s body’s going to go, I have to figure out who to invite, what church is going to be doing the service.” What’s really needed is pre-planning. And that led me to the whole Five Wishes thing. I think that, of course, it makes sense for someone my age and older to do something like that, but I think it makes sense for someone of any age to do it. One of the hardest things that I’ve seen are these parents who lose their child way before their time — in their 20s or 30s — and they have no idea what their child would have wanted. They have no idea what their interests were, what kind of music really spoke to them. They didn’t really know how to honor their child, especially when they became adults.

I think about this kind of stuff a lot, but I still haven’t done anything about it — I mean, I would trust my husband to make choices in my stead if I die. That’s kind of a morbid Newlywed Game, but I feel like we would ace it. But I should write that stuff down. I haven’t done it, even though I think about it all the time. And a lot of people my age don’t think about this all the time. I think it’s something most people want to put off as long as possible.

Right. But I think the fear, for me anyway, was that I don’t want someone deciding for me that I’ve outlived my usefulness and so they’re going to pull the plug. That’s sort of how I viewed it. The key is that this planning is for when you can’t speak for yourself. It doesn’t have to be a debilitating illness — it can be a car accident or you’re paralyzed, which could happen to anybody. And under those circumstances, I think it gives great comfort to those who are making those decisions to really know that this is what you wanted.

Did you think about this when you were younger? When you were in your 20s or 30s, what was your mindset about this kind of stuff?

No, I was not thinking of it in these terms. My thinking has really evolved over the course of time. My dad died when I was 25. I’d been to a lot of funerals, because we were Catholic and you kinda have to go to funerals whenever a family member dies, and we had a big family and all of that. But my dad wasn’t even Catholic. I was really upset by the fact that my mom — and it’s not my mom’s fault, she was just doing what came natural — but we had a Catholic mass and everything, even though he never went to church. I don’t even know how we got a mass, because they’re very serious about that kind of thing. Then the priest gets up and gives his eulogy, and he didn’t even know him.

One of the best memorials I ever went to, we all met in a park and stood in a circle and people started telling stories about the person who died. It was a friend of my daughter’s. And it was just really, really intimate. I felt connected to every one of those people through that event, more so than I’d ever felt at any other kind of memorial event. And that’s the thing that I think is missing. We have relationships with people from all different areas, and they all see us in a different light, and how cool is it if everyone can come together and say, “This is the piece I knew of her”? Everyone contributes their piece and all of a sudden everyone there gets a fuller sense of who the person was. And I think that’s a real comfort to the person who’s experiencing the loss most profoundly, because they realize that they’re not alone in feeling this loss, that the person is still very much alive in the hearts of so many other people. So that’s what my intention is, to really celebrate the life — to say, “This person was amazing.” Every life is amazing and if those stories can be told when everyone is together, I think it really honors the time that person spent on earth. That’s my goal. That’s what I hope to do.

It’s a really personal thing. It feels really important. Not that I’m important, but it’s a real kindness to people and it’s something that’s easy for me to do and not easy for them to do, and I’m happy to be able to provide it. I almost feel guilty charging for it, and I have to get used to that. I’ve never been a business before, so that’s a hard one for me.

There are two things going on: The actual memorial planning, which you seem to find very easy. But then there’s the business part of it, which is new territory for you. As a person starting a business, how has it been? Did WEV help you set it up, or were you on your own?

I meet twice a month with some of the other people who’ve taken the class — it’s called the MasterMind. It’s basically a group of people who get together and help people sort through their challenges in business and hold them accountable for the goals they set. Mostly it’s peers encouraging each other. So they definitely did help. But it’s way different when you’re planning it all out and putting the business plan together. Even though you’re doing market research and all of this stuff, it really is only hypothetical. I thought, for example, “Oh, I’ll just partner with the mortuaries! Because they, of course, will recognize that they’re not really caring for the families!” Oh, no. They see me as competition, so they don’t want to partner with me at all. They feel like they take good care of their families. And I’m going, “But you’re not with them — you’re with them at the service, you’re with them when they come in to buy your stuff, but who’s with them at home when they’re looking through photos and figuring out who’s going to bring who to a memorial and who they should call?” They’re not in any of that. They’re not doing any of that.

But I found that one of my greatest allies, and also one of my greatest pleasures, is working with the hospices. All of the social workers there know what I do, so if they come across a family who has no idea what to do, they’ll have someone to call. That’s been pretty good, but it’s still been really slow going. I’m developing all these different ways of getting out there. I do the Five Wishes for free. I’m a certified advanced care planning facilitator and I’m a notary, so I do it as a volunteer in the community. But I also will do it one-on-one with people. I have now booked two people who want to do it as a party — they’re going to have their girlfriends over and I’m going to tell them all about advanced care planning and what the different choices they have. I think it will be really fun. They’re people right around my age, in their 50s, and they’re thinking about these things — they’re thinking about it for themselves, but they’re also thinking about it because they’re watching their parents go through it.

I just got home from the hospital this morning because my mom had to go in for a procedure. She’s 80 years old and the truth of the matter is that anything could be the last thing that she does. It was supposed to be a one-hour procedure, but it took four hours. Even though I’ve had conversations with her and I’m her health care agent, I was going, “OK, is this the time? Is this it?” I know people who are my age whose parents didn’t think about this and the parents are at home, both are dying, and they don’t have the money to have around-the-clock care, so that means that the family has to do it. You think, “OK, I don’t want to be a burden to my children, I don’t want to linger forever, I don’t want to be stuck on a tube feeder for 20 years…”

When people come to you, do they usually have an idea of what they want? Or are you there to guide them?

So far, they’ve really known — “Oh, I’m going to bury.” Or, “Oh, I’m going to cremate.” What I’m working on is getting into the conversation before the death occurs, so that people can be more mindful about what they’re choosing. Right now I’m dealing with people where the death has already occurred and the decision’s already been made — unlike the way it was with my family and friends which was, “The death has just occurred and I don’t know what to do.” But nobody’s going to call a stranger and say, “Hey, I’m going through a really hard time. Will you help me?” That’s why I decided that I needed to do this preplanning and get my name and personality out there, so people will think about it. I’m actually offering memorial pre-planning where people sit down and write out exactly how they want their memorial to go, and then I’ll give them a document that lays it all out — like, “I want these flowers, I want this music played, these are the pictures I want set out.” I’ll help them do that, and then I guess I’ll give them a discount on it. [Laughs] I don’t know. I’m figuring it out as I go.

You said you were kind of uncomfortable with charging people because you love doing it so much, but you have to make money. What have you landed on in terms of what you charge people?

Funny you should ask that, because I was just working on it. I had this family who said, “Yeah, I just want the video.” And they proceeded to hand me a baggie full of pictures. And so I was like, “Oh, I have to scan all of these, Photoshop them…” I had only really quoted them on putting the video together. So I didn’t get paid what I should have gotten paid for that. I’m still working on it. The way I initially thought about it, I wanted to charge one fee just to hire me and everything else would be an add-on. But it was not enough, and I ended up getting screwed.

Do the people that come to you seem concerned about money? Or is it just like, “I’m going to throw some cash at you to make this not my problem anymore”?

It’s kind of like that. I was so nervous about it. One of the pieces of advice I was given was, “Don’t worry about other people’s pocketbooks — they’ll worry about their own.” It’s true. But I want to be able to give them the options to save money and really honor the person.

Pricing is hard. Especially in this situation where you love it so much, and the people are in a very vulnerable place.

And I don’t want to take advantage of them, but I also want to get paid. I’m still really mulling it over. It’s a process. It’s talking about something people don’t want to talk about, and there’s a very established process in place where everyone thinks, “I’ll just call the funeral home.” And I’m like, “Yeah, ka-ching.” Funerals can go from $12,000 to $20,000 and higher, depending on what you chose. I just want to be part of that conversation, to really explore all those things and not have people rushed into these decisions that they really can’t afford and then when it’s done they don’t feel any better and they’ve got this huge debt over their head.

Have you made plans for your own memorial service?

I would like to have a green burial, but my husband says he doesn’t want to be buried — he doesn’t want to be in a confined space. And I’m like, “Well, you won’t be in a confined space, because you’ll be dead.” But if I don’t do that then I’ll probably be cremated.

There’s other technologies coming along, too, that may become affordable. There’s alkaline hydrolysis, where basically they dissolve all of your tissue and it goes down the drain, and then they crush all the bones and that’s what you get. It has less of an impact than cremation, environmentally. And then there’s the mushroom suit TED Talk by the woman trying to create mushrooms that will detoxify her body as she decomposes, because of how many chemicals there are in us, and when we’re burned all those chemicals go into the atmosphere. Promession is where they freeze dry you and shatter you and you become compost or fertilizer for plants. It’s still in its infancy, this whole thing.

I have thoughts about my memorial, but the more I do this the more I realize that I could just say to my family, “Oh, whatever you guys want.” But for them, whoever’s left behind, I think it would be a lot easier for them to follow a roadmap instead of having to come up with something from scratch.

Have an idea for a future installment of Can’t Take It With You? I’d love to hear from you.

Rachael Maddux is a writer and editor living in Decatur, Ga. She writes the “Can’t Take It With You” column for The Billfold, a series about death and money.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments