When Things Fall Apart: The Cost of Divorce

by Peter Pacer

The last thing I ever expected out of my otherwise well-planned life was a divorce. I didn’t expect my marriage to last just 10 years and to be a single father at 37. Living through the financial impact of divorce has been like watching a tornado destroy what little I had built in my 15 years since finishing college.

Almost 17 years ago, I fell in love with a smart, beautiful, fun woman. I was a future architect living in Baltimore, fresh out of school making $23,000. We dated for six years, mostly long-distance, and nearly all of my disposable income went to pay for phone calls and flights to visit her while she attended college 1,000 miles away. I pinched pennies and lived an ascetic existence on tuna noodle casseroles.

She liked nice things, but wasn’t a princess. I considered myself a value shopper — the type of person who likes to save, but occasionally spends money to buy quality things. To wit: I paid for her engagement ring by selling a mutual fund I had bought five years prior. Before we got married, we went through Pre-Cana, a life preparation course couples must take before getting married in a Catholic church. We discussed the goals we shared, lifestyles we wanted, our careers, kids — the usual stuff — and more or less agreed on things. I knew we were a little different in our handling of money, but nothing that couldn’t be overcome. We were in love and we got hitched.

Married life was good for about six years. We rented a place in Baltimore and lived off my salary while she was in law school. By then, I had a graduate degree and was making about $44,000. We went on simple, fun dates and traded reasonable gifts. Shopping was rare because we couldn’t afford it. Eating out was a well-enjoyed date night treat. Our spare dollars were socked away for trips to visit family, and we bought a few loose stocks with bonus money.

My wife finished law school, and not being a cutthroat type in a cutthroat market, she struggled to find a job she liked in the Baltimore and D.C. area. The implicit brass ring from law school was for her to take over her dad’s small practice, or perhaps open a branch office. After a couple years of underemployment (her friends were averaging $80,000 a year, while she was at $35,000), I got a transfer with my company to work in Jacksonville, Fla. so she could move back to her hometown and work for her dad. She’d have mentorship, familiarity, no competition, stability.

Six years in, I was doing well as an architect. The market was hot and I had just received an awesome pay raise by switching jobs. I now made nearly $70,000. Against my better judgment, we decided to upgrade and purchased a spectacular home at auction — offloading our very affordable home at the height of the real estate bubble. Our new home would now eat up 55 percent of our income. It was as if my raise never happened.

Although she was barred in two states (that’s a good thing for an attorney), my wife worked for peanuts for her dad doing small town law, never making more than $52,000, and more often $40,000, while we learned that her friends with less experience made $120,000. The promise of firm equity kept me going, but we planned to have children to fill the new house we bought, and I worried that we wouldn’t be able to afford the life we wanted if my wife didn’t start earning more.

When our daughter was born in 2008, my wife never went back to work full-time. This wasn’t planned — it was a unilateral decision that I objected to.

While we were married, my wife was dealing with mild depression, but it was manageable with meds you have heard of. After our daughter was born, things started to turn south. To summarize the last four years of her medical history (and avoid a HIPAA violation), she had some physical health issues (multiple bone fractures and surgeries) and mental health issues (onset of personality disorders). Note well: Financial strife follows closely on the heels of health issues.

In 2010, some of her mental health issues surfaced. The market tanked and she now worked even less, earning about $25,000 a year as an attorney with $130,000 in outstanding school loans. She became suicidal and went on long-term disability. We were left riding one income in a budget built for two, a house built for four, many medical bills and prescriptions to fill, and a growing toddler to raise.

One of the many unfortunate side effects of my wife’s mental health issues was shopping: chronic shopping; addictive shopping; shopping to fill a bottomless abyss of pain and sadness; shopping to “rebel and punish”. Those were words she used. Any reason to buy a gift was a license to shop. At first, it wasn’t grossly negligent — just some extra lunches or tops, a book, or an extravagant hair-mani-pedi outing. It was $50 or $80 a month of money we didn’t have. Then $100 a month. Then hundreds of dollars appeared on our three credit cards. She bought shoes, handbags, jewelry. She bought 21 different perfumes.

My wife never did grasp that our lifestyle had to change when we had less income to live on. Her spending increased. Imagine working a full day and coming home to a spouse who was not working, but shopping online all day. This was my Groundhog Day.

It was now January 2012, and I tried everything to communicate our dire situation to my wife and what it would mean: repossession of her beloved SUV, no money for clothes for our daughter, the loss of our home. In an attempt to scare home the point of us being broke due to her shopping, I approached my in-laws for help. They were very much on my side, although they were historically cowardly parents — the kind who’d rather be your best friend than an authority figure. Her six-foot four-inch dad-boss-attorney had a one-on-one with her. It didn’t work. Nothing did.

A month later, I began confiscating debit and credit cards from my wife because she couldn’t stop shopping — all 11 of them. New cards would appear. I would gather them, pay them off and put them in the shredder. She hid her booty, lied to my face about her shopping and getting more credit. Four months earlier, my wife took it upon herself to spend $6,000 during the first week of November — an amount that more than tripled what we had spent on Christmas, ever, for both families and ourselves. I changed the laptop login to keep her from using the credit card info saved on various websites. She was under house arrest.

By now, my situation had developed into a disaster drama on so many levels — suicidal tendencies, drug addictions, work disability, multiple fender benders, binge eating, checking out from child care duties — that my spouse was unrecognizable from the woman I had married. It was so bad that my very Catholic parents told me, their very Catholic son, that I needed to get a divorce.

Sadly, underlying all those issues was the undeniable reality of having to navigate the day-to-day. “I’m sorry” doesn’t pay the bills. I met with an attorney in June and we separated on July 5, my own independence day.

The Cost of Divorce

There are some decisions in life that you should only do once, so you have to get it right. I believe marriage should be one of those. When it’s not, divorce should be. You have to get the right team behind you because you are making decisions that will affect you for the rest of your life, or at least until your children turn 18.

Divorce is a process, not a transaction. Like a chess match, no “game” is alike, and it breaks down into three financial phases:

1. The Opening

Meeting with a family law attorney will most often cost you a consultation fee — sometimes flat, sometimes based on an hourly rate. Mine was $350 for about 90 minutes. This is like a two-way interview. You get to measure the candor of the attorney, whether you trust they will go to bat for you, whether they have the experience and skill for your case. When you find someone you want to move forward with, they will require a retainer. This is most often a non-refundable amount of money that “hires” them and gets them started on your case. My attorney’s retainer was $5,500. I suppose it’s open to some negotiation, but these are standard fees and rates. My experience with attorneys (other than the fact I was married into a family of them) was paying $250 to make a ridiculous speeding ticket go away, so yeah, it was a major sticker shock. The retainer rarely covers the total work effort, and mine lasted a few months. Ask a lot of questions about the typical process, hourly costs, monthly costs, total costs.

2. The Middle Game

Depending on your case, whether it’s disputed or not, you will have monthly billings based on the attorney’s efforts. Mine cost $275 per hour. I heard of others paying upwards of $400 per hour. My total case lasted nine months. Some monthly invoices for me were under $1,000; others were $3,500. Everything is billed: emails, calls, research, paperwork, postage, and the expenses depend on the needs of your case. If you need extra effort — meetings, negotiations, court filings, hearings, depositions, expert testimony — expect to pay a lot. I needed all of the above at times, and that added up.

3) The End Game

Cases follow a typical trajectory: dispute, informal discussion between parties, organized meetings between parties (mediation), and if nothing can be settled, trial. Mediation ends many cases, some go to trial. After a day-long mediation, which cost $1,700 for the mediator, and about $2,500 for my attorney’s time, my former spouse and I came to an agreement — mostly to avoid court. All in, the divorce process cost me a hair over $30,000. Two minutes before agreeing to the settlement, I inquired about the cost of a trial, and he said “double what you’ve spent.” Enlightenment!

Lessons Learned

There have been so many for me, and I am offering things that engaged, seriously dating, and even unattached single people should be thinking about financially before marriage:

1. If you have assets of any sort to your name, get a prenuptial agreement.

Prenups are not just for trust fund babies and Donald Trump. Before marriage, I owned some loose stocks, mutual funds and my car — $20,000 max. My debts were about $20,000 in grad student loans. However, I had recently received a small five-figure inheritance. My wife’s assets: a car. Debts? $130,000 in law school loans. Naïve, trusting, and in love, I joint-titled everything, and lost half of the inheritance that was mine before the divorce. I will never marry again without a prenuptial agreement, unless I marry someone with far more assets than me, in which case I would completely understand having to sign one myself.

2. Keep your assets separately titled (car, property, credit cards, etc.).

If you like and drive each other’s cars, make it official and swap titles. If you ever need to sell something, like a house, it is easier if it is in one person’s name. There is no need to have joint credit cards unless one person has a horrific credit history; build your own credit individually.

3. Never co-sign on a partner’s debt.

I co-signed on part of my wife’s law school loans and realized later it was my credit history at risk if she/we should default. I was now responsible for decisions she made (law school, program cost, etc.). Those loans were the vicious variable rate government loans that could not be consolidated, so we paid those off first, but mostly with my salary.

4. If you’re a saver and don’t marry a saver, have separate pots of money.

Yes, I mean a joint checking account that pays the bills and separate accounts for playtime. Income disparity? Work it out. Who pays for what? Work it out. Don’t fall for the “we’re one team” and “what’s mine is yours” bullshit. Believe me, it saves resentment, and allows for true gifts and surprises to be given later. Bonus!

5. A spending addiction is every bit as serious as an alcohol or drug addiction.

The one time I was able to convince my wife to attend an AA meeting for spending, she was laughed out of the room and never went back. That was myopic and sad. An addiction is an addiction. My wife had both a drug and spending addiction, so I had a painful, protracted lesson in addictive behavior. An addict seeks an escape, rides a rush, experiences guilt, and then crashes. Repeat ad nauseum until there’s an intervention. No logic, no threat, no emotion can move an addict to change — it must come from within. After I asked for a divorce and we separated, my “shocked” wife racked up $18,000 in nine months shopping with her credit cards. She still has not hit bottom.

6. Deal with issues early and communicate.

If you notice a pattern, however small like a new Starbucks habit that costs $20 a week that goes against your couple’s philosophy or anything previously discussed, talk it over immediately. These things fester. Debt digs deep holes quickly.

7. Hold your spouse accountable for behavior.

If he or she goes on a spending bender, HE/SHE pays it back on HIS/HER credit card over time from HIS/HER paycheck. I paid off at least $35,000 in unauthorized spending from my wife in the past two years. I enabled too much for too long, and in the end, received no “credit” in the eyes of divorce law. In my case, it would have been much wiser for me to not have joint credit cards, and let the debt pile up on her cards. When we divorced, it would have been her debt to manage (unless it was for family purchases).

8. Be on top of family finances.

You don’t need to be a comptroller or do your own taxes by hand. There are no brownie points for that. Financial literacy might be an aspiration, but be on top of two things: balancing your checkbook monthly (with your bank statement in hand/online), and developing a reasonable budget (a bucket for every dollar you earn each month). Force yourself to track money trails. If you are lucky enough to underspend in an area, save or move that money so you won’t touch it. When you get those skills down (schedule them like a household chore if you have to), you can move on to investments and long-term savings goals like a house, grad school or retirement (highly recommended unless you pay someone to manage those for you). Online tools can help a great deal.

9. Don’t borrow from friends or family.

Unless you are starting a legitimate business, and they are truly investors, tapping friends and family for cash is cheating because there is a good chance what you need the cash for would not be loan-worthy from a bank (i.e. it’s to cover some irresponsibility or unnecessary purchase). If you borrow from friends or family, insist on drawing up a contract. Record whose debt, when, how much, repayment terms, interest, etc. Get it notarized. And especially if you borrow against an internal pot of money (401(k) loan, inheritance or earmarked account), create a formal IOU to pay yourself back. I lost thousands because I dipped into money that was mine or earmarked for a specific long-term goal with the intention we would pay ourselves back, and it never happened. As the law pretty much states, if it’s not in writing, it doesn’t exist. The old saw “it’s not personal; it’s just business” readily applies.

10. Insist on keeping your kids’ needs at the forefront.

I would live in a shoebox before I would subject my child to substandard daycare or schooling. Clothes, medical care, food, books all come before my needs, and I suspect this is the same for most parents. When push comes to shove, providing for the kids will usually bring most parents back to the reality of needs versus wants.

11. Enforce equality.

This is critical, especially if one person is a saver and the other is a spender. In 10 years of marriage, my wife always got the new car and while I got the hand-me-down. As I watched our financial house crumble, I felt obligated to be a financial martyr. A new handbag for my wife shows up? I put off the suit I really needed for work. Do a temperature check with friends and coworkers. Other guy friends had toys and hobbies — motorcycles, expensive golf clubs, wine collections — and I had nothing. I didn’t want any of that, but more importantly, I felt I couldn’t have it even if I wanted it. I have a high threshold for pain, but that degree of subordination from selfishness was too much to overcome.

When Rules Are Broken

If you suspect internal financial malfeasance (i.e. someone raided the cookie jar):

1. Keep a paper trail.

Keep credit card statements, bank statements, investment accounts — any summary of your assets and dates. Know what you have just in case your checking account gets emptied, or so an investment is not mysteriously liquidated without your knowledge.

2. Distance yourself from bad behavior that could affect you.

Close dormant or joint credit cards. Suggest opening a card in your name alone (pick one with different perks you want, as an excuse). Meet with bank personnel to protect accounts with passwords or limitations involving joint approval. Move non-essential funds from checking to savings, or better yet, make them disappear into short-term CDs.

3. Assemble your resources.

Prime your network of family, friends, coworkers — anyone you may need to rely on for advice, or, heaven forbid, financial or professional help. Make sure what’s happening to you is not normal couples behavior — you’d be surprised how distorted the view can be from the inside of something dysfunctional. Get commitments in case you need character witnesses or sworn statements about events or things like who is a better parent.

4. Keep a journal.

I would have overlooked so much about what was happening to me, even month-to-month, if I had not kept a journal. I uncovered patterns of behavior, and was able to remind myself to do, and not do things I would have otherwise forgotten. And it wasn’t always for bad times: my journal helped keep my morale up.

5. Get a lawyer.

An hour consultation with a family law specialist will run anywhere from free to $400 or more. A divorce is too important to opt out of an attorney because you don’t have the money. Call in favors, pay in tiny installments, barter, just find a way.

I’ve been living solo for almost a year. I took a few actions that provided some buffer from being flat broke when I filed for divorce. First, I was always the family money manager — I knew where the bodies were buried as an accountant might say. I knew how funds came in, what typical expenses were, and where I could borrow in the short-term to pay the next bill. Second, I insisted on carrying no balances on our credit cards. If not for this fact, I might still be living the charade. Not relying on credit shines true light on reality — what is sustainable behavior and what is not. My former wife made our financial life a farce. Third, no matter how badly we needed funds, I refused to stop contributing to my 401(k), so I knew we were never spending every single dollar, and were always saving something. Fourth, I refused to let us dip into easy money (my small inheritance I received) in order to pay for my wife’s shopping binges.

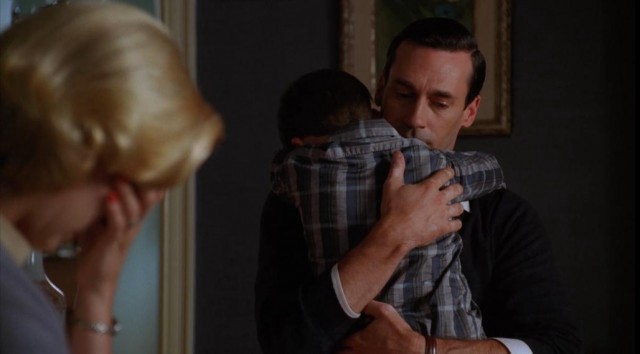

I had to give up half of everything worth anything. Due to our income disparity, I agreed to take on more of the costs associated with our house (I pay the mortgage until its sale) and daughter (daycare, health insurance), in order to avoid paying child support. We share custody of our daughter. I also negotiated a finite amount of alimony to be paid after the house sells — I’ll be truly financially emancipated when that’s done. And it’ll feel great.

Peter Pacer (a pseudonym) is an architect in Jacksonville making the best of his time tethered to Florida. He is an active parent, blogger, volunteer, runner, schemer, and scratch negotiator by necessity.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments