We Found Hope in a Mega Millions Ticket

by Mary Mann

When the manager at the wine bar said he’d hire me, I didn’t know what to say, so I said, “Really?”

I’d applied for so many jobs, I’d almost forgotten that the point was to actually get one. I moved to San Diego in the fall of 2008, fresh off an all-consuming break-up with my college boyfriend — I’d spent the last few months watching romantic comedies rather than the news, so the recession came as an unpleasant surprise when I began to look for jobs. San Diego’s economy depends on tourism, and as such it was a very dumb place to move just as “staycation” became a thing.

“Really,” he replied with a raised brow. “You start on Friday. Wear something nice. No open-toed shoes.”

The first few months in San Diego were full of so many concrete accomplishments — finding a house, getting a job, buying a bike, making friends — that it was almost impossible to feel restless. Every day was full and sunny and tiring. The wine bar was a 10-minute bike ride from the little house I moved into with a friend-of-a-friend named Mandy, the end house in a short row of four connected houses on the corner of Sunset Cliffs and Muir. Jasmine grew on the fence out front and sun streamed into our living room from the back courtyard. We paid $650 each, which was not much less than my monthly paycheck, but the beach was four blocks away. Like Mary Tyler Moore, just the fact that I was going to “make it after all” felt like enough.

At 28, Mandy was five years older than me and had lived in San Diego that much longer. Though she grew up in Missouri, she had the windswept, sunkissed look of someone born and raised on the coast. She was a waitress at a high-end seafood restaurant, but that was just how she paid the bills: She introduced herself to me as an artist.

When she said that — “I’m an artist” — I thought at first that she meant art was a hobby. Most of the people I was meeting in our neighborhood, Ocean Beach, introduced themselves as whatever they liked to do rather than what they did for a living. Surfer, rock climber, musician, yogi — all were common self-identifiers in a community of waitresses and bartenders.

But Mandy actually had a degree in woodworking. She’d even made a few tables, but the equipment and materials were too expensive without buyers, so by the time I met her she was in the process of transitioning to skateboard decks (the top of the skateboard before the wheels are attached). While I spent those early San Diego days on the beach — reading novels in the sand, swimming against the current, learning to surf with a few new friends — Mandy made the necessary calls to get a booth at the Wednesday Night Market on Newport Avenue. This was the arts and crafts market in Ocean Beach.

Mandy’s decks were beautiful — pieces of rare wood fitted together in a checkerboard pattern and polished until they shone — but at $200 apiece they were too expensive for the skateboarders in our neighborhood, all of whom were either middle-schoolers with small allowances or underemployed college graduates like us.

“People don’t know what art is worth any more!” Mandy railed one night, two months after I moved in, as we sat on the kitchen counter digging spoons into a container of mint chip ice cream.

I shrugged: “Maybe they’re just broke.”

I spoke from experience — my student loan grace period had just ended, and the wine bar paycheck was not enough to cover everything. Earlier that week I’d had to call our landlady Carol and ask her if there was any work I could do for her in exchange for a slight rent reduction.

“Are you looking for another job?” she’d asked.

“Yes, I am, I just haven’t found one yet. But I will.” I crossed my fingers as I said it. Carol agreed to let me do a few things for her. Twice a week I borrowed her car and drove her husband, who had Alzheimer’s, to the community pool, where he swam laps while I read on a bench. I also took care of her dogs when she was out of town and did some gardening at her various properties.

While I babysat Carol’s dogs and drove her husband to the pool, Mandy gave up on skateboards and decided to make jewelery — a craft she could do on the cheap. A piece of plywood laid across two sawhorses became her workbench, wedged between our entryway and kitchen. She bought pliers and bulk bins of bronze chain. She hauled dusty shoeboxes full of keychains out from under her bed, leading me to wonder what else she had stashed away — Mandy’s life was full of mysterious, unmarked boxes tucked in corners and on high shelves.

“I knew these would come in handy for something someday,” she crowed as she strung a Viva Las Vegas keychain onto a lengths of bronze chain.

By then we’d been living together for about six months. I had found a second job as a kayak guide, pointing out the sights of La Jolla Cove to paddling tourists from Arizona and Southern California — staycationers. From them I heard more rumblings about the economy — banks failing, companies going under, swindles exposed — but only to explain away their measly tips.

The job meant that I no longer had to do chores for Carol, but also that I no longer had days free to swim or read on the beach. I was paid to be in the sun and so I liked it less. I started wearing big straw hats, wrap-around shades, and swim-shirts with sleeves.

Most days I worked a double, kayak guiding during the day and hostessing at night. Mandy and I would get home from our restaurant jobs around the same time, elevenish — she would go straight to her workbench, while I curled up on the gold plush thrift store couch and read from the pile of novels that I checked out weekly from the library. She listened to music and sang along to Jane’s Addiction songs while she worked, sometimes asking me to try on a necklace she’d made so she could see how it looked. This companionship was comforting but after a while her industry started to make me fidgety. For six months, building a life in San Diego during the recession had been enough of an accomplishment. But now that I had two jobs and spent my days working for tips and paying rent, there wasn’t anything left to achieve. I wasn’t even “workin’ for the weekend” — I didn’t have any days off.

I was reading all the time. Novels, mostly, thick ones of the Great American variety, and I thought maybe I could write one too. My college laptop had Microsoft Word, and there wasn’t much else I needed to get started. So one night, as Mandy clipped chains and sang off-key, I began a novel about a boy my age named Hank, a receptionist at a wine magazine. His job was a lot like mine, actually. As were his habits and circumstances. I worried about this and so I made him a smoker, because I had never been able to pick it up, even though I’d tried.

Now Mandy and I worked together every night, she on her jewelry and me on my novel. We taped inspirational quotes to the wall. Thoreau was a favorite: Go confidently in the direction of your dreams. Cautiously, we crept forward in the direction of what we hoped would be our dreams.

One night at work I read an article in The New Yorker about the failure of the banks in Iceland and I had a panic attack. I had never been to Iceland and didn’t know anyone from there. But I also didn’t have any savings or any possibility of savings and I didn’t even have a boyfriend to weather 2009’s economic storm with. Even my parents were in debt. All I had was an active imagination and a propensity for anxiety.

I told my manager that I felt sick — “maybe food poisoning” I said, glancing subtly at the cheese rinds that the line cooks left out for the staff to snack on — and he sent me home early. The house was empty. I paced and muttered and drank a glass of boxed wine, but only began to calm down when I opened my computer and wrote a scene in which Hank reads a New York Times article about the failure of the banks in Greenland and has a panic attack.

And so the sun-filled days passed.

Mandy didn’t sell any jewelry. The Wednesday Night Market crowd passed by her booth without a glance. In my novel, Hank’s roommate Berg was also unable to sell any of the wooden spoons he whittled while singing along to Porno for Pyros. Both Mandy and Berg decided that the problem was their jobs.

“This restaurant lifestyle is killing us,” Mandy said one night as we took a break from our creative endeavors to eat Walgreen’s off-brand ice cream sandwiches on our front stoop in the cool, salty night air. “Look at us. It’s two o’clock in the morning and we’re still awake. Working. Eating. Drinking shitty wine. Every night. It’s unhealthy! How can I work well if I don’t live well?”

“Yeah, it’s the pits. But what can we do?” I ate my ice cream sandwich slowly, nibbling around the edges.

Mandy finished her sandwich in two bites and crumpled the paper wrapper into a ball. “I’ll figure out something.”

Once she made a decision Mandy was quick to act, and a few weeks later she quit waitressing and took a day job at a plant nursery in Encinitas, 30 minutes up the coast. “It’s a better environment,” she said. “Peaceful. Inspiring.” The air in the nursery was moist and cool and smelled green. Mandy claimed to be happier; more spiritually fulfilled.

Until she saw her first paycheck. Minimum wage without tips meant that she was making less than half of what she’d made at the restaurant. She put her car payments on one credit card and her student loans on the other. “You should ask Carol about driving her husband to the pool,” I suggested. “He has some great stories, even if they’re the same every time.”

“I don’t want to have to do more work! There has to be a better way!” Mandy moaned as she dropped her head down on top of her work-bench, causing several lengths of chain to rattle and a few magazine clippings to flutter to the ground. A keychain rolled under her chair. “I hate worrying about money. I. Hate. It.”

She called in sick to work the next day and spent 24 hours in a jewelry-making frenzy. Then she got a call: The price of the booths at the Wednesday Night Market had gone up. She would have to pay more or lose her spot. She lost her spot.

The next night I biked home in a red-faced fury. A middle-aged man had called me a “pretty idiot” because I made him wait for a table, and my manager had yelled at me for not knowing that the middle-aged man was one of the restaurant’s investors. In my head I was already writing a scene in which Hank would have to take a phone call from a very famous and very rude wine-maker. But Hank wouldn’t be forced to apologize to the stone-faced man with salt-and-pepper hair and ice blue eyes and then go cry in the bathroom. Instead, Hank would just hang up on him and go smoke a cigarette. His boss would admire his gumption, and might even decide to send him abroad on an exciting top-secret wine-finding mission.

When I got home, out of breath and agitated, Mandy was curled up under a blanket on the thrifted couch that we never sat on anymore because we were never not working, even when we were home. She was watching Under the Tuscan Sun and drinking wine from a juice glass, which she raised gleefully when I walked into the room. “Look what I checked out from the library!” She gestured towards the television, where Diane Lane was cooking spaghetti for a group of Polish construction workers in a Tuscan villa.

“I forgot all about this movie,” gushed Mandy, not noticing my flushed face. “This is how we’re meant to live! I swear to God, I’d be in Italy in a second if I just had the money. Everything would be different…” She swirled the wine in her glass and gazed hungrily at the television.

Over the next week, Mandy watched Under the Tuscan Sun over a dozen times. Even now, years later, I can still hear the theme song from the DVD menu in my head: wordless, cheerful flutes and strings… The piles of art and architecture magazines that had teetered around her work-bench finally engulfed it, burying the keychains, bits of wood, fiberglass flakes and sketches. Mandy left the house only for work and to buy the ingredients for a series of increasingly complicated pasta dishes.

It was summer by then, the heart of tourist season in San Diego, and both my jobs were getting busier and more stressful. There was a plus — more people meant more tips — but it wasn’t fun. After one particularly long day spent dealing with difficult customers, both at sea and in the dining room, I left Hank alone on my computer screen and joined Mandy for the umpteenth living room screening of Under the Tuscan Sun.

“I should have been born Italian,” she said as the golden light of Tuscany suffused our living room.

“And rich,” I added as I took off my shoe so that I could whack a spider with it. We seemed to have an infestation. I suspected that they bred in one of Mandy’s many mystery shoeboxes.

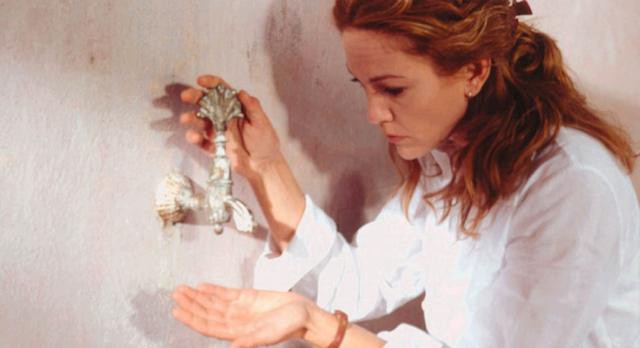

The next day Mandy came home with a grin that threatened to overwhelm her face. I had never seen her so happy. I was standing over the sink in the kitchen, eating a piece of peanut butter toast. I had just changed from the bathing suit and swim shirt that I wore as a kayak guide into my hostessing black dress. My hair was still wet.

“I have big news,” said Mandy as she grabbed my hand and led me to the couch — the gold plush felt soft and warm and nap-worthy in the late-afternoon sun — to show me what she’d bought. “It’s all my dreams come true,” she whispered as she handed me a piece of paper with shaking fingers.

The lottery ticket was one of the Mega Millions tickets where you get to pick your own numbers. Mandy told me that she had closed her eyes and emptied her mind and the numbers had just come to her. She felt them in her bones. And the lotto was high this week.

“Like $300 million,” she said, “if I take it in installments, or you know, $200 million, cash. I haven’t decided.”

“Well, you have to win first…” I began cautiously, but Mandy waved a hand as though swatting a fly. “I know, I know,” she said. “But listen, people win the lottery all the time. If someone has to win it might as well be me, and I should plan so it doesn’t take me by surprise. I’ll take the cash, I think, and just get on the first plane to Italy. First class! I’ve never flown first class before. Then I’ll buy a house like in Under the Tuscan Sun, with some land for a vegetable garden, olive groves, wine bushes, or whatever they’re called.”

“Vineyards.”

“Yeah! Vineyards. I’ll have some of those. Hey, I can open my own winery! I’ll hire some cute guys to help. And a cook. And I’ll have a studio built on the property so that I can work on my art with no distractions. And I’ll never wait on anyone again. People will be waiting on me!”

“That sounds awesome,” I conceded, leaning back on the couch (after checking for spiders). “My God, if I could just not deal with assholes anymore…”

I turned my head to look at Mandy and saw her moving past me, down the road to a real, grown-up life. Even Hank had moved past me: he no longer answered phones — I’d sent him, all expense paid, to Italy. Why couldn’t the same thing happen to me?

“Oh Mary. I’d… I’d give you some.” Mandy said shyly.

I felt a frisson of something… luck? The sun was suddenly richer, golden, like the Tuscan light.

Logically I knew that it was a bad idea to believe in Mandy’s dream of the lottery, but this was the moment when I decided to put away logic for a while. Mandy was depressed and grasping at straws, but I was anxious and overworked. We both needed hope. And, I told myself winning wasn’t completely impossible. Growing up I had a friend whose family bought a lottery ticket every week and one day won $1,000. Just like that. People really did win the lottery all the time. Real people.

“No, no, you don’t need to do that,” I demurred.

But she insisted — a million. “I’d have plenty left,” she said. “And who am I if I can’t think of my friends when I’m rich?”

I could picture myself in Europe and Asia and South America: wandering around cities, renting boats and bikes and motorcycles. When I was tired of traveling I’d buy a house with a floor-to-ceiling library stocked with every book I ever wanted to read. And of course I would quit both of my jobs.

The hostess stand swam into view. I saw myself standing behind it as if it were a normal day. I’d wait until my manager — who’d been promising to promote me to server for months — said something condescending, and then I’d shove the reservations clipboard off of the hostess stand and tell him that… he could suck it.

I’d have to work on a better speech, I thought, but I loved the idea.

“Oh Mandy, I don’t know what to say,” I finally replied, clasping both of her hands in mine. “Thank you! Oh thank you!” I giggled, suddenly shy, and she giggled too, and we hugged each other tightly on the thrift-store couch. Dust motes hung around us like stars in the shafts of afternoon sun.

That night I got home around midnight, later than usual, because the manager had asked me if I could run food and bus tables after my host shift. It was a dirty job but I would get a bigger portion of tips from the pot at the end of the night, so I spent my evening taking away the used plates of happy rich people, and arrived home smelling like mussels, steak and coq au vin — splashes of each dish on my dress.

Predictably, Under the Tuscan Sun was on, but instead of watching it Mandy was drawing on a sketchpad. “Blueprints for my villa,” she answered when I asked what she was drawing. “You know, just in case.”

I went to bed without working on my novel but I lay awake for hours, my muscles twitching with tiredness, thinking about Mandy’s lottery ticket.

Some people have plans. My friend Neha knew in high school that she wanted to be a research biologist. Another friend, Emily, had known that she wanted to be a dentist even earlier, so early that she didn’t remember when. I never knew what I wanted to be. Somehow I always figured that something would just happento me. Like Elizabeth Bennett meeting Mr. Darcy, or the Pevensie children tumbling into Narnia through a wardrobe.

Headlights from the street near my window climbed up the blinds, illuminating the motivational post-its on the wall. Maybe, I thought as I drifted off, maybe the lottery was my something.

We had three days until the results were announced, and for those days Mandy and I floated everywhere, held aloft in the bubble of our 300 million dollar secret. It was implicitly understood that the word “lottery” was verboten. If we’d told anyone else about it, even talked about it with each other, it would break the spell.

At the restaurant my manager complimented my improved attitude, which he qualified by adding: “Not that you’re usually all that bad. Just…tired. Customers want peppy.” Back at home, Mandy took a break from Under the Tuscan Sun and cleaned the house. When she finally found the spider nest in a box of old drawings under the couch we both ran from the house screaming. We exterminated them with hairspray.

As a kid I had said my prayers every night before bed, and while we waited for the lottery results I took up the habit again. I couldn’t explicitly pray for the lottery — I didn’t want God to think I was only in it for the cash — so instead I prayed for my family and friends and even for my manager. I avoided stepping on sidewalk cracks, and threw salt over my shoulder whenever I spilled any while refilling the shakers at work.

“Goddamnit,” my manager rubbed his eye as he caught a face full of salt. “What are you doing?”

“Sorry, won’t happen again!” I chirped, silently finishing the sentence with: because I won’t be working here.

The day came for the drawing of the numbers. I was rereading Anna Kareninaat the host stand but it was hard to focus on the tragic life of rich Russians when I kept mentally rehearsing versions of my job-quitting speech in my head. I’d deliver it that night, I decided, as soon as I got the word from Mandy. My heart was thudding: would I really make a scene in the restaurant?

I was running through a mental list of grievances to mention — from my measly salary to the indignities inherent in “the customer is always right” — when I got a text from Mandy:

We didn’t win.

That was all.

I didn’t text her back. What could I say? I’m so sorry or We’re morons. I thought about how Hank would deal with this set-back. I wished, not for the first time, that I smoked.

Mandy was in her room with the door shut when I got home at the end of my shift. I could hear sniffling, but she didn’t come out to say hello. So I walked into my own room and closed the door.

On my bedside table was my computer, which contained the neglected life of Hank. Inspirational post-its were scotch-taped to the wall around it. I dropped my bag on the floor and sank down on the bed. I stank of mussels in a white-wine butter sauce.

Go confidently in the direction of your dreams. I read off of the Thoreau post-it.

Live the life you have imagined.

After the day we didn’t win the lottery, Mandy and I were more careful with each other: both more gentle and more distant. Over the next few weeks Mandy decided that plants were her true passion — her job at the nursery had made her realize it, she said — and so she packed up her jewelry in more shoe-boxes and made plans to move to Hawaii, where she had been promised work on a farm. Meanwhile, I got a third job as a ropes course facilitator, opened a savings account with my first $50, and biked to the library for a copy of Financial Planning for Dummies. I wanted to go on a trip somewhere, anywhere, once I saved enough.

As for Hank, he stayed where I left him, smoking lazily beneath the Italian sunset, waiting for me to join him. Seven months later I did, after a fashion. I did go traveling, but I went to Vietnam instead. It was cheaper.

Mary Mann is a native of Indiana. She lives in New York.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments