The Affordable Care Act: What It Is and What It Isn’t

by Stone Goldman

The Affordable Care Act is not a type of care or a health plan. It’s a law that makes everyone get health insurance and provides financial support to help people do that.

So: We can stop calling it Obamacare. It would be nice if it actually was Obamacare — if, in 2014, you could go down to your local government building and get your government-issued Obamacare card and show that to your doctor who would swipe the card and give you health care. But that would be called a public option, and the health insurance lobby made sure that went nowhere (please see: death panels, the fate of Clinton’s Health Plan).

What the insurance industry did allow to happen was the enactment of a complex system that says in 2014, you will need to have health insurance from a private health insurance company. Exactly what you would expect. But don’t head out to join your local chapter of the tea party just yet. In exchange for mandatory insurance, the people of this country will get better and more affordable (and in some cases free) insurance.

So what does this mean for you? That depends on whether you have insurance or not and, if you do have it, where you get it.

• If you are one of the 157 million people with employee-sponsored health insurance (half of the country), things shouldn’t change much. This law wasn’t really designed for you. (However: If you have crappy employer-sponsored health insurance, they will have to give you better coverage.)

• If you are on Medicaid, things shouldn’t change for you either.

• If you buy health insurance on the private market, that insurance should get cheaper (through something called community rating provisions, which “prohibit the use of previous healthcare claims or health status as a factor in premium determination, and premiums for older Americans can be no more than three times that for younger Americans.”) Private market benefits should also get better.

• Finally, and most importantly, how will if affect you if you are among this country’s 50 million uninsured or 50 million underinsured (paying more than 10% of your income for insurance through co-pays and deductibles)?

First off, if you get insurance, you get a tax rebate. Or, if you prefer the language, if you don’t get insurance, you pay a tax penalty.

Uninsured and underinsured people will either qualify for the expanded Medicaid (for people with about $15,000 annual income) and can get care through that program (provided your state participates) or will be able to purchase insurance through the health exchange.

The government is providing money to states to set-up these exchanges, which are basically websites where you enter your info and will be given a menu of insurance plans you can purchase. The deadline for the exchanges to be operation is January 1st, 2014. They may roll out gradually, but I doubt many states will be handing this assignment in early. To see an example of an exchange, check out the Connector in Massachusetts. Go to their site, enter a fake MA zip code — try 02201 for Boston — and experience the future.

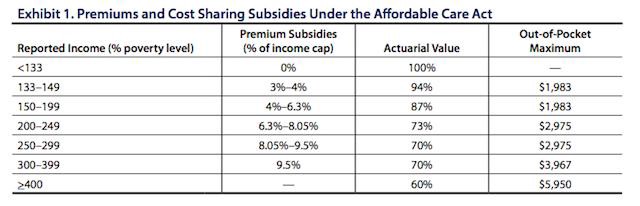

So: That’s how you’ll buy healthcare. But if you make less than 400% of Federal Poverty (44,680 for single, 92,200 for family of four)the government will subsidize your healthcare so that it is no greater than 9% of your income. The less you make, the higher the subsidies. Here’s a chart detailing the subsidies from a Commonwealth Fund article by Jonathan Gruber and Ian Perr:

If it will cost more than over 8% of your income to buy insurance, you are exempt from this mandate to purchase insurance. The CBO estimates that in 2016, there will still be 30 million people without insurance, but most of them will not be subject to the penalty. Immigrants for example, will be exempt. (For more information on possible penalties for the uninsured, this report from the Congressional Budget Office is a good resource.)

So, how do you pick insurance once you are given your nifty menu? The government only counts health insurance that meets certain minimum standards of coverage. Gone are the high deductible plans with no preventative care. Now they must provide certain benefits and a minimum amount of coverage.

The plans are grouped into four groups which have different percentages of cost sharing. They are bronze (60%), silver (70%), gold (80%), and platinum (90%). The cost sharing will be through some mix of co-pays and deductibles, so if you have a bronze plan they will have to at least cover 60% of the costs. Compared to a high deductible plan, which covers nothing until you hit several thousands of dollars of damage, this is a dream.

The four levels of coverage are based on “actuarial value.” Actuarial value is a measure of the level of protection a health insurance policy offers and indicates the percentage of health costs that, for an average population, would be covered by the health plan. (Employer-sponsored health insurance will now have to meet these minimum standards as well.)

At the webpage you will likely be shown the different tiers and the monthly price. I’m not sure how the subsidies will be displayed, perhaps it will be discounted from the price shown, but you will get your menu and pick a plan from there. Purchasing insurance intelligently often requires looking at annoying charts which list out benefits. If these exchanges are good, they will have a comparision option so you can look side-by-side at plans.

I think the best way to shop for insurance is to think of your regular medical needs and see what you will have to pay out of pocket based on the information provided. So if you see a doctor rarely, and the co-pay is $40 in an inexpensive plan and $20 in a more expensive plan, than you may want to consider the less expensive plan because you don’t utilize that service. However, if you think you may need medical care because of your lifestyle (you bike without a helmet) or there is a history of chronic illness in your family, you may want to pay more for a plan with less cost sharing. Another thing to consider, in addition to your current needs, is you potential needs and how those scenarios will play out. Like a bike accident in one plan versus another.

The plan benefit charts should have a table listing co-insurance rates, rates for hospitalization, rates for ER visits, pharmacy benefits, and co-pays. Try to fit these vague numbers into actual scenarios. Additionally, they may provide you with the option to look at the full benefits offered.

Check out this example of a more extensive plan summary. If you look through it, you will see the innumerable scenarios that are taken into account and the co-pays for them. Don’t freak out about the pages and pages of information. Insurance companies can calculate complex risk, you canot (or at least, not without driving yourself crazy). So: Do an assessment of your needs, take into consideration what you can need and what you are willing to pay, and then pick a plan. Too much stress can lead to hypertension, don’t let picking health insurance make your health worse.

And that’s basically it. No death panels. No storm troopers. Just a webpage and a monthly payment adjusted for your income. Is it the best solution? Maybe, maybe not. But for now, it’s a way to get healthcare and save you from potential bankruptcy.

Stone Goldman (not his real name) is a health policy analyst who has worked in various high level government positions in the health care field. Got health care questions? He’s got health care answers: stone.goldman@gmail.com

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments