Used Books, New Books

I think this particular comment is worth pulling out from yesterday’s post on cheaply acquired books, because it’s an important point about how we balance being thrifty with being socially conscious consumers. Authors don’t get paid from the sale of used books, but they may gain readers who will support them in the future. We want to support businesses like the Paradox Bookstore, while also supporting writers, editors, and designers by paying full price for books. Why not do both? Support your local secondhand store, or church, or wherever it is you’re going to find secondhand books, but buy new ones from your favorite authors as well.

If you went to college, you probably were required to spend thousands of dollars on books, and as someone who had to take loans out to pay for these books, you probably bought many of these books used, and then sold them back to the bookstore after your courses were completed. This is unfortunate for the authors and publishers of those books because they didn’t see a dime from any of those sales. It’s likely that most college students aren’t aware of this, and they’ve (we’ve) also become conditioned to seek out used books, or get their books at a discount by shopping on Amazon.

I was that college student, and am guilty of seeking out the lowest prices on books I could find in an attempt to offset the cost of my expensive education. But as I’ve built my career as a writer, and have made friends with other writers and authors, I’ve switched gears from being that kid in college looking for the lowest price, to being more conscious about how my dollars affect writers like myself. I’ve lost jobs and watched friends lose jobs as writing and print journalism was declared a dying industry. And an answer to that is to put my dollars at work. I’ve gotten to a point where I can afford a digital subscription to The New York Times, and to buy new books I want to read when they come out, so I do. And when I don’t have the money, well, The New York Public Library is a wonderful institution, and I am thankful for it.

I’m reminded of a scene from You’ve Got Mail — which I re-watched last weekend after Nora Ephron’s passing — the one where the famous children’s author stops by Kathleen Kelly’s independent bookstore, The Shop Around the Corner, to ask her how business is doing after the mega-bookstore Fox Books opens down the street. The author tells Kelly she’ll support the indie bookstore any way she can, but then later appears at a signing at Fox Books. The Shop Around the Corner is eventually put out of business. Words of support only go so far. Money goes much farther.

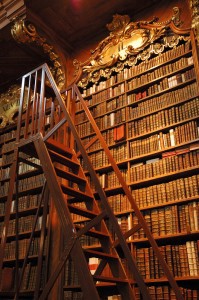

But our pockets are only so deep. And secondhand books have their own sort of magic about them. Author Julian Barnes recently wrote about secondhand books, and the future of books, in an essay for The Guardian:

By now, I probably preferred secondhand books to new ones. In America such items were disparagingly referred to as “previously owned”; but this very continuity of ownership was part of their charm. A book dispensed its explanation of the world to one person, then another, and so on down the generations; different hands held the same book and drew sometimes the same, sometimes a different wisdom from it. Old books showed their age: they had fox marks the way old people had liver spots. They also smelt good — even when they reeked of cigarettes and (occasionally) cigars. And many might disgorge pungent ephemera: ancient publishers’ announcements and old bookmarks — often for insurance companies or Sunlight soap.

Barnes has also evaluated the age of the e-reader and has come to the following conclusion:

Books will have to earn their keep — and so will bookshops. Books will have to become more desirable: not luxury goods, but well-designed, attractive, making us want to pick them up, buy them, give them as presents, keep them, think about rereading them, and remember in later years that this was the edition in which we first encountered what lay inside. I have no luddite prejudice against new technology; it’s just that books look as if they contain knowledge, while e-readers look as if they contain information. My father’s school prizes are nowadays on my shelves, 90 years after he first won them. I’d rather read Goldsmith’s poems in this form than online.

I believe that books will earn their keep — but only because I know that I’m willing to pay for them. Just promise me you’ll buy my book when it comes out someday. And if you buy this theoretical book used, well, I promise I won’t give you a hard time about it.

Photo: Shutterstock/Andre Viegas

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments