Open Your Mail

One tax mistake took me seven years to pay off.

I was 23 when I got my first book advance money, for selling a young adult novel based (not so loosely) on my time at a small, hippie liberal arts college. It was a modest amount, but it was a check with my name on it that I’d earned through writing. I called it “Book Money,” always capitalized in my head, and bought a new mattress with it. It seemed like the most Adult thing I had ever done.

It wasn’t like I was a stranger to the idea of taxes. I had seen Rachel on Friends freak out wondering who FICA was and why he got all of her money. I’d held a variety of part-time jobs through college, although my earnings were meager. After college, I got a job as a legal assistant, and I continued to do very Adult things like sign up for a 401(k) plan and spend my lunch hour every other Friday running to the bank to deposit my paycheck.

In the back of my head, I knew I should be saving a percentage of my Book Money for taxes. I even knew it in the front of my head. But there was always something — a roommate who hadn’t given me rent money on time, late fees added to an electric bill, expensive car repairs. I’d never owed taxes before — I’d always over-withheld at my jobs, and received a check each January for the difference. If anything, I told myself, it would cancel itself out.

It didn’t cancel itself out. I was also surprised — genuinely surprised, which shows the depths of my naivete — that I was taxed on the full amount of the advance, an amount I’d never even seen because my agent had taken out her percentage before she passed along the remainder to me. This was all very above-board, and exactly how it worked in the literary world. I didn’t know, so I thought maybe there had been a mistake.

“You employ me,” she explained on the phone when I called. “So you get taxed as my employer, essentially, and then I get taxed on my income as your employee.”

She said more — about accountants and write-offs and all kinds of advice I could’ve stood to take — but I was too focused on seeming like I’d known all along. “I just wanted to check,” I said casually, before changing the subject.

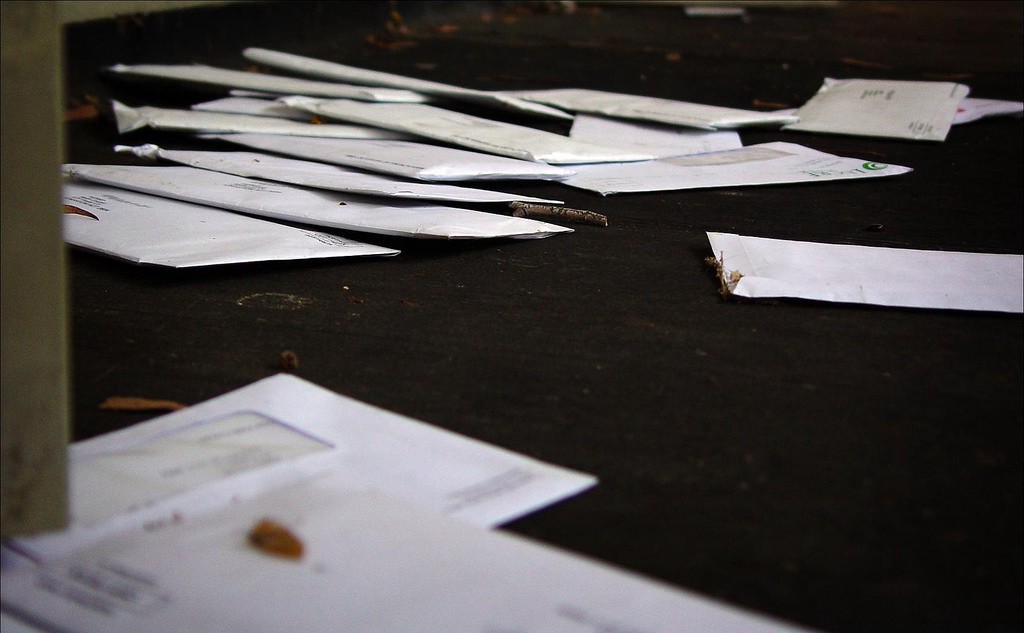

My newfound Adultness broke down. I delayed filing because I knew I would owe money that I didn’t have. Then I didn’t file the next year, because by then I hadn’t filed the year before, so shouldn’t I do that first? Any letters I received I put in a box, unopened. I knew what they were going to say, I told myself. They were going to ask for money that I didn’t have.

I thought about it every day, until I didn’t. Until the letters came less frequently, and it was relegated to the occasional pit in my stomach, the twice-a-month insomnia inducer, the yearly freak-out in mid-April. It’s easy to avoid things, until it’s not.

You know that saying, about death and taxes? It’s true. I was basically living in a fiscal version of Final Destination, a movie I’d only seen once and found incredibly stressful. Instead of Death, it was my Debt that was chasing me, and no amount of hiding or hoarding letters was going to keep me safe.

Eventually, the IRS garnished my wages, because that’s what they do with deadbeats. I was 28 by then, with two children — a two-year-old and three-month-old — and a husband who was alternating being at home with them and going back to school. My income was all we had, and it was already stretched thin.

The new law firm where I worked was gossipy and toxic. The payroll department was now privy to my personal failures, but I hoped to keep it as quiet as possible around the rest of the office. There was a copy place on a lower floor of the building where we sent our boxes of discovery and trial binders, and the owner was always really nice, staying late to finish rush jobs himself or bringing us cookies to thank us for our business.

I used my lunch hour to go down to the copy shop, hoping to prevail upon them for an empty office, a telephone, a fax machine. They set me up, and I called the IRS to discuss the appropriate steps I would have to take in order to set up a payment plan and stop the garnishment. At the end of the call, when the representative asked me for a fax number to send the paperwork for me to sign, I found out that the copy place’s fax machine wasn’t working.

“Can’t you e-mail it?” I pleaded with the rep.

“Sorry, ma’am, we can only do it by fax.”

I thought of the fax machine upstairs at the law firm. In order to ensure that we never missed a document, it was set up so that all incoming messages were immediately e-mailed to every single person in the firm. I explained the issue to the IRS rep.

“We could mail it,” he offered.

That would take days. Even after I submitted the paperwork, they warned me it could take weeks for everything to go through and lift the garnishment. I couldn’t take the hit of another partial paycheck.

“Just fax it,” I said, and I gave him the number.

I made a lot of mistakes. Starting, of course, with not setting aside a percentage of the Book Money in the first place. Allowing the IRS to fax sensitive personal information to my entire workplace was not my finest hour, either.

But my biggest mistake was in not facing it once it had happened. If I had filed my taxes, even without having the money I knew I was going to owe, I could’ve entered into a payment plan right away and paid literally one-third of what I ended up paying after all the fees and penalties.

Over the four years I paid back the IRS, slowly but surely, I had several long phone calls with their representatives. Sometimes it was because I needed documentation from them, since my records were a mess. Sometimes it was because I was late on a payment and had to work something out. But they were never as scary as I thought they would be.

I spent one particularly long call with a guy in Virginia, who thought it was “awesome” that I was a writer after I explained my situation. His computer was taking a long time to load, and so he filled the time chatting about books. He recommended The Art of Fielding to me, and it sounds like a really good novel and one I’d enjoy, but I’ve never picked it up. It represents a tiny corner of the shame from that whole experience that I still avoid, even now that my debt has been paid.

“Did you, like, get letters?” he asked me. “Or were they not coming to you?”

It was sweet of him to give me the out. “No, I got letters,” I said. “I just didn’t open them.”

He laughed, perfectly at ease as he waited to update my bank information, process my payment, send me on my way. “Ah,” he said. “You gotta open them. It’s not so bad if you open them.”

Adulthood can feel like a series of envelopes, filled with stuff you don’t want to deal with. I would still prefer to pretend my car can limp along for just a bit longer, or my sore throat will go away on its own, or my air-conditioning will never go out in the middle of the summer.

But I try to remember the lesson from the tax mistake that took me seven years to resolve, and ended up costing me way more than if I had dealt with it in the first place. Those envelopes, the ones you’re avoiding?

Open them.

Alicia Thompson is the author of the YA novel Psych Major Syndrome and the co-author of the children’s series The Go-for-Gold Gymnasts. Her work has appeared in Narratively, Racked, Atlas Obscura, and Paste, among other outlets. You can find her on Twitter @aliciabooks.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments