I’m Not Good With Money Anymore, And I’m OK With That

On the cost of peace and one very good, very expensive decision.

Today I logged onto the Chase website to pay my credit card bill and was baffled by the numbers on the screen. I could empty my checking account and I wouldn’t be close to paying my balance in full. I clicked back and forth between my credit card statement and my payment history to make sure Chase Bank had not accidentally miscalculated my debt, as though some error-prone banker with a calculator was manually adding up each of my transactions.

Let’s not spend too much time in the weeds here. I paid the bank what I could, which was not enough, because I am living beyond my means. I’m spending more than I’m earning. I’m bad with money for the first time in my life.

My financial predicament doesn’t exactly surprise me; I made every choice in a series of decisions that put me here. In January I quit my job and moved to a different city, back into the co-op that I had moved out of in 2014. When people asked me why, I told them I wanted to write more and that I missed living with a community — both accurate statements. But here’s the truth that buoys those desires to the surface: 2016 was a hellscape for my mental and emotional health and I desperately needed to re-learn how to be a functioning human, which itself felt like (and is) a full-time job. I felt isolated, exhausted, raw, depressed, frozen. I was the flesh-and-blood version of an Alanis Morisette song.

So I saved some money and moved back to Austin, where I would be surrounded by a significant contingent of my chosen family, intending to write and stretch out my budget until I no longer felt like a robot with existential anxiety.

I am here, four months into this self-funded life sabbatical experiment extravaganza. A clenched fist around my soul has begun to loosen its grip. I’ve found some part-time work to pay my rent. Every day I share a meal or a beer or a late-night conversation with people I love. I’m writing again, I feel truly at home, and I’m drinking in the glorious freedom of being accountable only to myself. I don’t want to be the dork who’s like “I exorcised my demons through dancing!” but listen: I’ve found myself at 2 AM in my unlit kitchen dancing with some fiercely incredible women, and those moments have changed the way I feel inside my own body. “I’m filling the reserves of resilience that I depleted in 2016,” I told a friend recently, and the ability to even say those words was a blessing so overwhelming that it felt like magic.

But gracelessly wedging its way into my emotional rebirth is the annoying reminder that my wellbeing has a price tag. Between the journaling and the reading and the hippie sunshine sisterhood, I’m staring at my credit card bill and praying to find fraudulent charges. I wore my contacts for an extra month to save money. I feel more secure and fulfilled than I’ve felt maybe ever, and I’m draining my bank account dry.

It’s not that I failed to plan. I’ve been “good with money” since I’ve had money, so I thought I could accurately predict how long I could scrape by on my savings. I knew I would have to spend much less when I moved, and I have eliminated most of my discretionary spending. When I was a money-savvy bad bitch with a steady paycheck, I logged on to Mint.com every day, categorized each transaction, and tweaked my budget periodically so I could put money into savings. I liked going through the motions of checking my bank balances and watching my spending habits closely. If I was over budget one month, I would spend less the next month. That ritual — of planning where my money would go and keeping track of it when I spent it — made me “good with money.” The ritual reassured me that I was good and stable and smart.

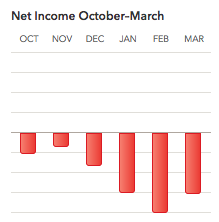

Now that my income has dropped off, I check in on my spending a couple of times a week at most. I don’t see the point in being as disciplined as I was before, and I sure as hell don’t want to see that little graph in the left-hand corner of the Mint website telling me that I’m hemorrhaging money.

It wasn’t the ritual of money management itself that made me feel good. It was the gratification that came from reassuring myself that I was responsible. And not just garden-variety responsible, but responsible enough to possess some kind of unassailable responsibility safety net. These days, though, I pull up my credit card statement or a bill and all the numbers tell me that I’m fucking up. I’m no longer interested in the ritual because, at least from the money perspective, the ritual tells me that I’ve made the wrong life decision.

But I haven’t. I know that. Moving back to Austin, living with my best friends, and being more selfish with my time has been one of the purest, most valuable blessings of my life. 2016 weakened me. I endured loneliness like I’ve never known, relationship turmoil like I’ve never known, health issues like I’ve never known, all in concert with the inarticulable feeling of being lost in the universe that I share with many people in their mid-twenties. And then, the election — a moment that spotlighted how precarious and hostile the world can be. When I finished moving my boxes into my room at the co-op, I sat on the floor and cried. I was exhausted, and moving to Austin was my solution. I had hope that it would work. I was terrified that it wouldn’t.

It did work. Here, I have room to breathe and be still. I am surrounded by friends who make me feel safe and loved and cherished. After a long year that drained my emotional energy and stoked my cynicism and depression, this moment in my life isn’t just meaningful. In a way, it feels lifesaving. Also, expensive.

I’ve been underemployed by choice for two months, and now (shockingly) I’m forced to reckon with the consequences: I’m not tone-deaf enough to miss how indulgent all of this sounds. Living beyond one’s means is not a calculated decision for most people, if it’s on the table at all. I’m a woman of color and I come from a family of immigrants; I’ve never had the kind of money or entitlement that enables people to, for example, travel for six months after college to “find themselves.” But as a middle-class single woman with a college degree and no dependents, I do have a cushion of privilege that allows me to feel relatively safe taking some time to do work that doesn’t bring in cash. The need to find more work will become pressing soon, but I’m confident in my ability to trade my labor for capital when the time comes. This indulgence will eventually end.

But I realize now that my income does not matter more than my wellbeing. I still work but on my own terms, and only a fraction of that work is rewarded with money. The rest is activism, writing, emotional labor, art, community-building. I spend time interrogating and educating myself on the type of equitable, anti-oppressive world I want to build—a task that feels urgent at this juncture in history. In short, for a moment I have the freedom to labor in a way that is healthy, purposeful, and relatively non-coercive. The world we strive toward should treat that freedom as a necessity, not a luxury.

Molly Crabapple interviewed porn star and activist Stoya last year, and part of their conversation has lodged itself into my brain. Stoya says:

“Money exerts behavioral control in so many ways; that’s the frontline of behavioral control in the US. You spend your childhood hearing you have to do this and that to get into a good college, to get a degree to get a good job and buy shit. It’s not even presented as ‘buy shit’ but as having things integral to adulthood, to fulfilling the promise of the American dream, like a very large house that costs a lot to keep warm in the winter. That’s broken in me. I don’t have that button. I don’t have the ‘how will you have that lifestyle’ button. I just sort of don’t care.”

The experience of prioritizing my humanity over money has changed me, both as a person and as a laborer. That button that Stoya talks about — mine does not work very well anymore. I enjoy feeling it break.

Natalie is a writer and activist living in Texas. She’s on Twitter and writes a newsletter.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments