What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: Susan S. Adler’s ‘Meet Samantha’

Where do we even START with this.

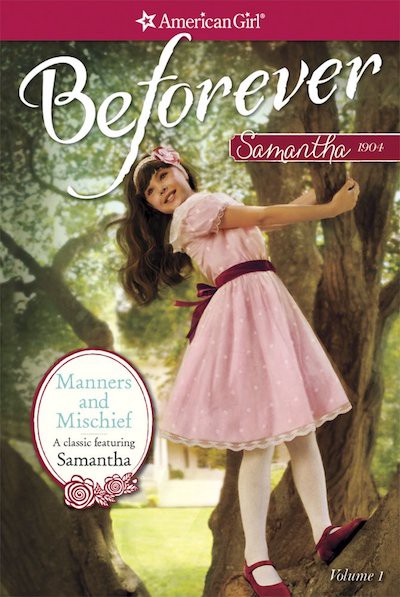

So the book I am holding in my hands is technically not Meet Samantha. It is Manners and Mischief, a new volume in the American Girl Beforever series that features the first three Samantha stories in one non-period-accurate package. (1904 children’s fashion, as anyone who remembers the original Samantha knows, had dropped waists.)

I was originally going to review Manners and Mischief as a single volume, but I got about three pages into the “formerly Meet Samantha” section and realized that it deserved its own entry.

So we’re going to get THREE STRAIGHT WEEKS of Samantha Parkington analysis.

Which is good, because there is a lot to analyze.

The Book Formerly Known As Meet Samantha deals with three intertwining plot points:

- Will Samantha receive the $6 doll she wants? (This doll would cost $155 today, which is almost exactly what it costs to buy a Samantha Beforever doll plus accessories and books. I refuse to believe that is a coincidence.)

- Will Samantha make friends with her neighbors’ new housemaid?

- Will Samantha discover why Jessie, her family’s seamstress, has disappeared?

The thing about the American Girl books is that they’re trying to teach historical and contemporary lessons simultaneously, so one of the first things Samantha does is ask her grandmother (“Grandmary,” and yes, she’s the only guardian in rich orphan Samantha’s life) if she can work to earn the $6 doll she wants. That’s the contemporary lesson—if you want something, you have to work for it—immediately followed by the historical lesson, which is that ladies in 1904 do not earn money. Then nine-year-old Samantha, who is apparently up on her current events and social movements, mentions that some women (like her Uncle Gard’s special friend Miss Cornelia) think that ladies should be allowed to earn money, so they won’t have to be dependent on a man.

Just… WOW. Okay. Does Samantha even know what being dependent on a man means? Or is she willing to say anything to get that doll? Either way, Grandmary decides that Samantha can earn the doll through good behavior, and a week later deposits the doll on Samantha’s pillow, meaning that good behavior is worth $0.86/day, or $22.19/day after 112 years of inflation.

Of course, the idea that “ladies should not earn money” is directly contradicted by the two other main characters in this story: Nellie, the nine-year-old housemaid who just got hired next door, and Jessie, the household seamstress who disappears for reasons Samantha cannot fathom, because although Samantha is well-versed in women’s rights issues she hasn’t yet learned how to recognize pregnancy.

We’ll deal with Nellie first. I have no idea whether befriending the housemaid next door is in any way historically accurate—my instincts say no, but I wasn’t around in 1904, anything could have happened—and Samantha decides that Nellie will be her friend against Nellie’s will. The text literally says “there was nothing [Nellie] could do to stop her new friend.” Nellie is just a young girl trying to get a job done and Samantha is actively preventing her from doing that by showing up and saying “Hey, want to hang out in this hole in the lilac hedge? It can be our secret playhouse!”

(Side note: children’s books convinced me that sitting inside bushes would be a lot more comfortable than it is in real life.)

Nellie gets fired. FROM HER JOB. The neighbor family says it’s because she isn’t “strong enough,” which might be a fair assessment of a nine-year-old girl, but it could also be because Samantha keeps showing up with gingerbread cookies and grand visions of teaching Nellie how to read.

However, it all turns out okay because Samantha gives Nellie her $6 doll as a “sorry you got fired” present. Then Grandmary is all “what did you do with your doll?” and Uncle Gard’s like “she gave it to the servant girl next door,” and Grandmary says that Samantha’s sense of value is in the right place, by which she means Samantha’s sense of value is aligned perfectly with 1980s standards.

(Second side note: I know you’re thinking “don’t you mean 1990s?” but Meet Samantha was originally published in 1986.)

Now let’s look at Jessie, the black seamstress who works for the Parkington family while her husband Lincoln works for the railway. Samantha loves Jessie and Lincoln because Jessie tells Samantha stories and Lincoln brings Samantha small presents like postcards and candy. Which is possibly historically accurate—again, I wasn’t there—but the idea of Lincoln bringing presents to the little white girl who lives with his wife’s employer doesn’t read very well from a 2016 perspective.

Do Jessie and Lincoln truly like Samantha? When Samantha insists that Nellie take her to the neighborhood where Jessie and Lincoln live, under the cover of night because that makes it more like an adventure, are Jessie and Lincoln glad to see her? Are they happy that she disrupted them while they were caring for a newborn? Is Lincoln really glad to leave his wife behind with the newborn while he escorts the two girls back to their homes? Is he at all nervous to be walking alone, at night, with two young white girls? Does any of this tie into why Nellie got fired two days later?

We see all of this through Samantha’s eyes; her excitement at going out after dark, her discovery that there are certain parts of town where Jessie and Lincoln are not allowed to live, her joy at seeing the baby and solving her mystery. (Nellie, we understand, has already solved the mystery but she still lets Samantha figure it out for herself.)

It would be fascinating to re-read this story from Jessie’s perspective.

So that’s Meet Samantha. We’ll do Samantha Learns A Lesson, aka Samantha Learns That the Working World Exploits Children, Which Is Something She Really Should Have Learned in the First Book, next week.

The discussion room is open and ready.

Previously:

What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: Thomas Rockwell’s ‘How to Eat Fried Worms’

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments