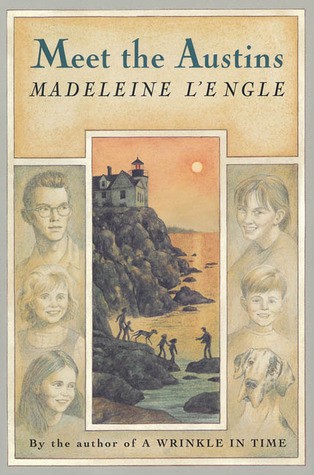

What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: Madeleine L’Engle’s ‘Meet the Austins’

Money can’t buy you love.

There’s a scene, right near the beginning of Madeleine L’Engle’s Meet the Austins, that just about heartbroke me when I was a child. I would read those few pages over and over to both indulge in that feeling and, in a way, prepare myself for it.

Here’s what happens: the Austin family has recently taken in an orphaned ten-year-old girl named Maggy. The Austin siblings know they are supposed to be nice to Maggy, but they’re having a hard time of it because Maggy is both disruptive and destructive in her grief. So we get this scene, where Maggy decides she wants four-year-old Rob’s stuffed elephant:

As soon as Maggy saw Elephant’s Child she wanted to hold it. Now, maybe it wasn’t very generous of Rob to say no, and pull away, and hold Elephant’s Child even closer to him, but in his place I think I’d have felt exactly the same way.

Maggy pouted, but she didn’t say anything and kept on walking up the hill, just behind Rob. When we were almost at the house she reached out and grabbed Elephant’s Child and raced on ahead with it, laughing in a horrid, screechy way, keeping just out of reach of Rob and winding the key to make Elephant’s Child play.

Maggy breaks the music box inside Rob’s stuffed elephant. It’s this little microcosm of a story about setting boundaries that other people ignore, and getting your stuff—or your self, because Elephant’s Child is clearly a transitional object for Rob—broken.

But then the tone shifts, and the story goes back to childish melodrama. “Can’t your mother and father get him another?” Maggy asks, before explaining that she always got new toys whenever she broke hers. You can read this as Maggy exaggerating her own self-importance, and L’Engle makes it clear that Maggy is prone to exaggeration, but this question is the start of Meet the Austins’ central theme: money vs. love.

See, Maggy’s parents were rich. Her grandfather, who is still living, is still rich. But these people never loved Maggy. “All the toys and clothes in the world and not one moment of spontaneous family love,” Mrs. Austin tells her children.

As an adult, I find that hard to believe. (Not one moment?) I also find the “she’s rich but not loved, we’re not rich but we have a lot of love” comparison a little difficult to accept, because the Austins might not be rich but they are living an enviably comfortable life. They have a four-bedroom home with a kitchen, a living room, a study, and an office in which Dr. Austin practices medicine. Plus a barn, where oldest son John is building a space suit.

They can take in a fifth child without worrying about how they’re going to feed and clothe her, or where she’s going to sleep. When the power goes out, it’s because of a storm, not because they’re having trouble paying the electric bill. When Vicky Austin breaks her arm, nobody worries about how much her hospital stay will cost. (Also, she breaks her arm and gets six stitches on her chin, and because of that she stays in the hospital for two days. This book was published in 1960.)

The big question, of course, is whether Maggy will continue to live with the Austins or whether her rich grandfather will demand she live with him or another rich relative.

There’s also a third option: Maggy could live with Elena, a professional concert pianist whose husband, Hal, was killed in the same plane crash that killed Maggy’s father. Maggy’s father’s will even states that Elena and Hal should be Maggy’s guardians if anything were to happen to him. But, as Dr. Austin explains:

“It isn’t as easy as that, John,” Daddy said. “In the first place, legally, a wish like that isn’t binding. You can will your property, but, according to the law, you cannot will a person. You can only express a wish. In the second place, Aunt Elena doesn’t have Uncle Hal anymore. She’s all alone. She leaves for a nation-wide concert tour next month, and she has a living to earn. And for her own sake she needs her music right now.”

None of the characters ever suggest that Elena should give up her career to raise a child. They don’t ask her to cancel her tour. The Austins, who are close enough to Elena and the late Hal to consider them an honorary aunt and uncle, support both Maggy and Elena—who are both grieving—by taking Maggy in and letting Elena continue her work.

They do, however, suggest that Elena could raise Maggy if she had another adult to help her… for example, Dr. Austin’s brother Douglas, who has had a crush on Elena since forever. If Elena were married, then Douglas could take care of Maggy while she was touring! It would be a perfect solution, except for the part where Elena just lost her husband. Still, the novel ends with Douglas kissing Elena, and you don’t need to read the family tree in the back of the book to understand that they will eventually marry and adopt Maggy.

After all, they may not have a lot of money—actually, it’s pretty unclear how much money they have, and I’d put them both as middle-class—but they’ve got a lot of love.

There’s one more scene I need to mention, and it’s the one where the Austins decide to play a trick on a visiting guest by pretending to be poor. It’s kind of grotesque, honestly, especially in the context of the “rich vs. love” dynamic, but the Austins dress up in their shabbiest clothing to go meet a woman whom they assume is Douglas’s girlfriend (it’s not, he’s only ever loved Elena, that’s not creepy at all), with the idea that if she doesn’t like them at their worst, she can’t love them at their best. Because ripped-up, ill-fitting clothes equals bad, I guess. Go back to your four-bedroom home, y’all. In a few years, your oldest son will be an astrophysicist and your oldest daughter will be able to communicate with dolphins. You’ve got love and wealth, and you had it all the time.

Previously:

What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: Frances Hodgson Burnett’s ‘A Little Princess’

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments