How “Choice” Feminism Limits Us All

Let’s shift focus from individual decisions to collective solutions

Judith Shulevitz, in her thoughtful and thought-provoking New York Times piece from this Sunday, maintains that “it was in many ways easier to be a working mother in 1980, when Chelsea Clinton was born, than it is today.” (The title of the piece is silly but the content is smart.)

Work days were shorter. Nobody expected you to get back on email after putting your kid to bed; there was no email. There wasn’t even “Cheers” yet, just “M*A*S*H” and “Magnum P.I.” More people had union jobs, complete with protections that would feel quaint or astonishing to many of us today.

Shulevitz goes on to argue for policies to make it possible for people who must become temporary caregivers — particularly mothers of young children — to take time off without suffering the penalties that currently exist. On-ramping after time away is notoriously difficult. Some women who leave to take care of little kids find they can’t return at all, whereas others must cope with a loss of salary and position that they can never recoup.

Shulevitz writes:

What if the world was set up in such a way that we could really believe — not just pretend to — that having spent a period of time concentrating on raising children at the expense of future earnings would bring us respect? And what if that could be as true for men as it is for women? …

care is work and caregivers merit the same benefits as other workers.

And the crowd goes wild.

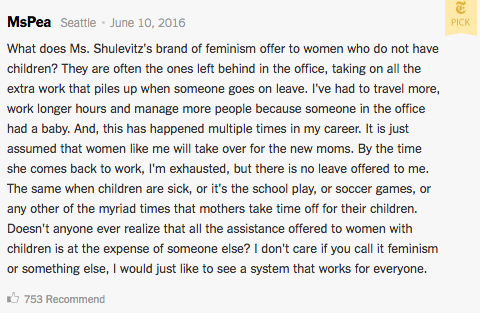

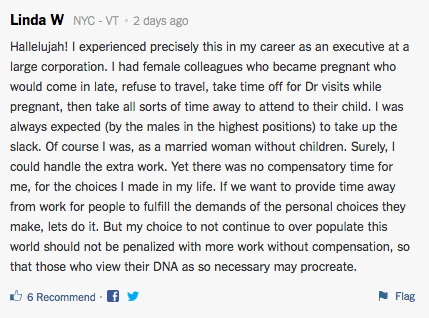

The most popular comment right now is by a woman who resents the fact that, throughout her career, she has been expected to do “extra work” left undone by moms in the office.

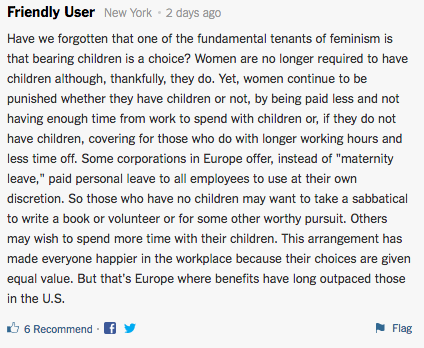

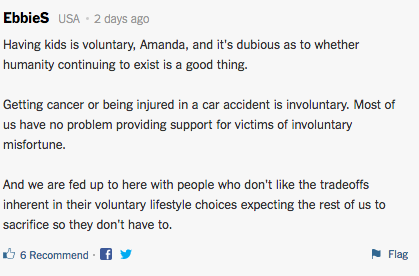

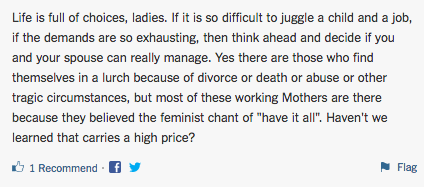

Lots of other commenters replied to MsPea, and as you scroll through their responses, you may notice a theme.

Yikes.

Do you remember that Daisy Buchanan, from The Great Gatsby, has a kid? Odds are you don’t. Her child barely features at all; Daisy ignores her, and so does Fitzgerald, after noting her existence. He doesn’t even go to the trouble of calling Daisy an indifferent mother. Yet she is, as are Anna Karenina, Scarlett O’Hara, Becky Sharp, Emma Bovary, and lots of others. Interesting women in literature rarely make good moms. Given a choice, few of fiction’s leading ladies probably would have had children; but they weren’t given a choice. All of them hail from a pre-birth-control era. To a degree, then, they’re forgiven by writers and readers alike for not throwing themselves into parenthood.

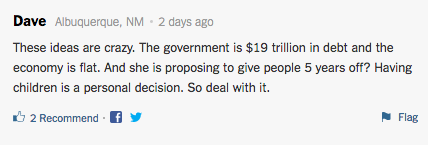

Nowadays, though, as you can see repeated over and over in those comments above — and in every comments section on every article that mentions paid leave, including those on this site — women have a choice. The implication is that, since women could choose not to have kids, those who make a decision to reproduce should stop complaining about the consequences. No sick days? No paid leave? No support? No sympathy. As Dave from Albuquerque says, “Deal with it.” Stop trying to “have it all.”

What is “it all,” anyway? I’ve never been clear on that. A career and a family? Is that it? Have we become so jaded as a society that we’re really comfortable saying it’s unreasonable to expect to find some amount of fulfillment both at work and at home?

Regardless. The choice thing cuts both ways. People expect more of moms now too, since they presumably became parents on purpose. Gone are the days when Betty Draper-types can drink wine in the backyard, smoke while pregnant, and let their kids put dry cleaning bags over their heads. Parents spend more time actively parenting now, at a time when employees also spend more time working. No wonder so many of us are exhausted. No wonder so many of us feel like we’re not doing anything well.

I understand why “choice” was an important concept for feminists to emphasize, especially in the initial decades of the second wave. The right of each person to determine her own destiny seemed key, even revolutionary, at a time when too many women felt constrained. And I will go to the barricades fighting for everyone’s bodily autonomy, especially the ability to make her own reproductive decisions. Outside of discussions about health care and abortion, though, I’d argue that the emphasis on “choice” hurts us more than it helps us. We’re all more limited than we might wish. Wealthy white women may have choices. (See: the amazing Anna Camp opting out in “The Good Wife” and then again as Deirdre in “Kimmy Schmidt.”) But in most families, parents can’t choose whether or not to work. Wages have stagnated while costs have risen, so two-income households are often a necessity. Many people don’t actively choose to become parents, either. Half of all pregnancies in America each year are unplanned. That’s millions of people each year just trying to make the best of an mishap.

In theory, I get the emphasis on individual empowerment. In practice, we’re not as guided by self-interest and free will as we might like to be, and besides, our fellow Americans seem to read the emphasis on “choice” as selfish. Over and over again in various comment threads, I’ve seen people demand, “Why should I have to support your choice?” The bickering that ensues — What about global warming? Oh yeah, what about social security? — is dispiriting and unproductive.

A feminism that isn’t all about “choice” might work harder to see everyone as part of a larger community, one that advocates for, and benefits from the inclusion of, parents and child-free people alike. Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Sonia Sotomayor! Sandra Day O’Connor and Elena Kagan! Plenty of policies would serve this larger community, including a $15 minimum wage, sick days, and paid family leave. Sabbaticals. Telecommuting. And, to go back to Shulevitz, shorter work days for all employees would be nice too.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments