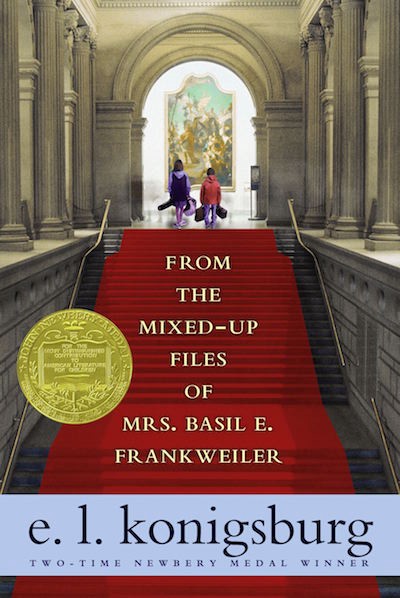

What Children’s Lit Teaches Us About Money: ‘From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler’

What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: E.L. Konigsburg’s ‘From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler’

Welcome to the third installment in What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money, aka “my new favorite thing ever.”

After examining The Hundred Dresses and Sarah Plain and Tall, I’m taking Billfolder Ravenclawed’s suggestion to look closely at From the Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler, which I always read as “Frankenweiler” when I was a kid.

(This is also a hint that if you suggest books in the comments, they might make it into future installments. Just a hint.)

Here’s what I remember about this book, which might represent what I took away from it as a child:

Claudia and her little brother decide to run away from home and move into the Metropolitan Museum of Art. They pack their clothing into instrument cases to disguise the fact that they’re carrying suitcases. While in the museum, they hide from the night guards by standing on top of the toilets (so the guards won’t see their feet peeking out from under the stalls). At night they play with all the museum stuff before going to sleep in antique beds. They wash their underwear in the museum fountain, which turns it gray for some reason. They also collect coins from the fountain, which they use to buy food from the Automat.

At some point there is a mystery plot involving an angel statue that might have been carved by Michelangelo. This plot is way less interesting than the part of the book that’s about two kids eating Automat food and hiding from guards. Still, the mystery must be solved, and so the two kids follow clues until they find the titular Mixed-Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler. Then Claudia takes a long bath in Mrs. Frankweiler’s house and decides she doesn’t want to tell anybody that the statue was carved by Michelangelo because some secrets should belong just to her or something. I’ve read this book more than once and I can never remember how the angel plot resolves.

Okay, so I got a few of the details wrong. The kids wash their bodies in the museum fountain, not their clothes (they use a laundromat for that, and their underwear comes out gray because they don’t separate lights and darks).

They also don’t play with the stuff in the museum, they study it—which leads to the whole angel mystery plot and the eventual meeting with Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler.

You could easily say that this book is about money—the very first chapter is about Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler updating her will, and financial transactions both enable and limit everything Claudia and her brother Jamie do—but, more than that, it’s about value.

Claudia Kincaid runs away because she doesn’t feel valued. She doesn’t want to come back until she finds a way to “feel different,” which is to say until she finds a way to value herself.

Claudia takes Jamie with her because he has literal value. He owns $24.43, earned from a combination of allowance-saving and cheating at card games. Claudia also saves her allowance in preparation for her adventure, giving up hot fudge sundaes except for the one day when the drug store puts them on sale (because you can’t turn down a good deal) but even then she can’t save enough.

Claudia believes—and this is where it gets tricky, because Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler is actually narrating the story, so I have to read it as Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler assumes Claudia believes—that her lack of income contributes to her lack of value, first because her parents are too “stingy” to give her a larger allowance, and second because she doesn’t have enough disposable income for anything besides hot fudge.

Before her decision to run away, deciding what to do with the ten cents left over from her allowance had been the biggest adventure she had had each week.

But with Jamie along, she has spending power. With more money, she can make bigger decisions. She can make herself valuable by placing herself in charge.

So the two of them take the train from the suburbs to New York—after Claudia mails both a letter to her parents telling them not to worry and two corn flakes box tops so she’ll have the 25-cent rebate waiting for her when she returns—and Jamie immediately begins putting limits on her leadership and her spending. They can’t afford taxis, he explains. They can’t even afford the bus. $24.43 isn’t going to get them that far (not even in 1967, when this book was published), and if they’re going to hide out in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, they’re going to need to walk forty blocks to get there.

I still think the section describing how Claudia and Jamie take up residence in the Metropolitan Museum of Art is the best part of the book. Who else read this as a child and immediately began planning how they would hide in a museum, if given the chance? I love all of the details; hiding in the toilet stalls, learning the guards’ schedules, blending in to school groups so they can learn more about the exhibits. I love that they wash themselves in the museum fountain and discover that they can use the fountain coins to replenish Jamie’s dwindling supply of cash.

Because the cash does go quickly—mostly on the two meals the children allow themselves each day—and they learn, literally, the value of a dollar.

Konigsburg isn’t coy about the numbers, either; she tells us how much everything costs, to the point where you can almost calculate their balance from page to page. I love the idea that this book is written in part for the children who know that they get 50 cents in allowance every week and that they’ll have 10 cents left over after they buy a hot fudge sundae; the ones that think about their money and track their money and wish they had more money—maybe twenty-four whole dollars. (That’s essentially a year’s worth of 50-cent allowances, all at once.) Konigsburg writes about money the way some authors write about food: in mouthwatering, vicarious detail.

Although Konigsburg tells us exactly how much money Claudia and Jaime have, I can’t figure out how much money the Kincaid family has. We know that they live in the suburbs, and we know that their children have picked up on the idea that everything in life costs money; we also know that each of the four Kincaid children has their own bedroom. But there are these weird little tells sprinkled throughout the book, like Claudia’s mother not buying her children’s school photographs, that suggest the Kincaids are either house-poor or extremely frugal. If we take Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler’s version of Claudia’s story at its word, the Kincaid children go to a school where they have slightly less money than their peers, and significantly less allowance money—but there’s nothing to suggest they’re low-income.

I’d like to read the Kincaids as the type of parents that spout financial advice at their children (“those school pictures are a waste of money!”) and charge them 5 cents for every day they fail to make their beds (“you have to learn the value of work!”), and who in turn unwittingly make their children feel less valued than their peers at school, whose parents gush over their school photos and don’t dock them a nickel every time the beds aren’t made.

It is worth noting that, when Claudia learns that her parents are worried about her, she is surprised. Some of this can be attributed to childish self-centeredness, but I suspect that love and money are treated the same way in the Kincaid family: handed out only sparingly.

One of my favorite parts of the book: as the children prepare to visit Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler, Jamie finally feels financially secure enough to start buying things without first asking what they cost. Two train tickets and a taxi ride later, they’re broke. It’s a moment that Claudia initially lauds as character development—“That’s a first for you”—and quickly turns into disaster.

The mystery plot parallels the primary plot in an interesting way; the museum wants to know if the angel statue was carved by Michelangelo in part because they are curious if the art world severely underestimated its value. Claudia feels a kinship with Angel, to the point where she claims she and Angel look alike (Jamie doesn’t see the resemblance), and it makes sense: she’s questioning her own value, which she believes can only be granted by people in power (specifically, her parents), and she’s also hiding her worth in plain sight.

Once she and Jamie meet Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler—and there’s so much packed into that meeting that it seems almost spoiled by the ridiculous “now that we’ve had all these great subtextual conversations about self-worth, you have one hour to find the answer to your mystery in my mixed-up files,” which, come on—she realizes that she doesn’t need her parents or anyone else to tell her she’s valuable, any more than the art world needs Michelangelo’s name to know that Angel is valuable. The value isn’t in Claudia/Angel’s net worth, it’s in who/what they are.

So, even though she has the answer to her mystery, she decides not to tell the museum.

There’s a little coda to this, in that Claudia is a one-month-from-turning-twelve-year-old girl and Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler is a widowed, childless 82-year-old woman. Even though both of them know (or are beginning to know) their value, they also want to keep this piece of knowledge about Michelangelo from the world in order to feel “special,” because the world does not specifically grant value to almost-12-year-old girls and 82-year-old widowed, childless women. (We’re several decades before “tween” becomes a marketable demographic. Remember that Claudia’s only real spending option for her limited allowance is ice cream.)

So Claudia decides to give value to Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler by visiting her and making her an unofficial grandmother, and in return Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler gives value to Claudia and Jamie. (I’m envisioning this as the three of them sharing the emotional and financial resources that the Kincaid parents don’t provide, although that’s my personal take on the story.)

In other words: Claudia learns not only that she has self-worth, but that she also has the power to give worth to others.

And I’d say you don’t need money for that, except we end the story with Claudia and Jamie discussing how they’re going to visit Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler as soon as they’ve saved up for the train.

Next week: Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

Previously:

- What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: Eleanor Estes’ ‘The Hundred Dresses’

- What Children’s Literature Teaches Us About Money: Patricia MacLachlan’s ‘Sarah, Plain and Tall’

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments