Working as an Obamacare Navigator and Fighting the State of California for a Paycheck

An email popped in from a woman who wanted to buy health insurance through Covered California, California’s health insurance exchange. She was having trouble creating an account password, a process that can be difficult if you’re not into following on-screen instructions. I wanted to call her right away, as she asked, but I was home with my kids — three wild toddlers who typically don’t allow me to verbally communicate with others. I suggested that we correct the problem via email or text. She wrote back: “HERE’S A THOUGHT…HIRE MORE PEOPLE.” I replied with a short e-lecture on rudeness. She quickly answered, “EAT SHIT.” As a distinguished representative of the state of California, I maintained my professionalism and wrote back, “Your mama.”

I became a certified enrollment counselor for Covered California after 15 hours of online training. My job was to provide assistance to people looking to purchase Obamacare insurance, or sign up for free Medi-Cal, my state’s version of Medicaid. The pay was commission only: $58 per successful enrollment. I was excited about the job because I had a decade of experience in community health care and was a passionate advocate for the Affordable Care Act. More importantly, I figured I could make good money if I signed up just a small percentage of the 200,000-plus San Diego County residents who enrolled last year.

I created an outreach plan for the upcoming open enrollment period. It was based on enrollment barriers that I had seen while working on similar projects: transportation, computer illiteracy, and lack of health care navigators available during evenings and weekends. My services would be mobile (I was unable to afford a real office) and I would assist clients any time of the day or week. I’d also target places where the unemployed and underemployed tend to be during typical working hours: libraries and malls and living room couches.

I had my first client within a week, a woman in her early 50s whose husband had lost his job as an executive in the defense industry. She needed help figuring out this “Obamacare thing.” I had learned in training to never say Obamacare, and had received a stern follow-up email telling me to scrub the term from my website. “Sure, I can answer questions about the Affordable Care Act,” I said.

I went to see her that same day. She lived in a spacious and elegant home, a place that I could buy if I helped just 17,000 people sign up for health insurance. We completed the application and she chose a gold tier health plan that cost a bit less than $400 a month. I had earned $58 in just over an hour, to be paid by the California Department of Health Care Services.

Shortly thereafter, I reached an agreement with a library to provide onsite enrollment. I was stationed there two hours a day, two days per week. My office was a folding table near the library’s entrance, but closer to the bathrooms. I said hello to everyone who walked in. If they dared to do more than nod in response, I’d immediately ask, “Do you and your family have health insurance?” I never thought I could be as annoying as a mobile phone rep working out of a mall kiosk, but I had also never worked on commission. Soon, I was enrolling up to 10 people per week.

Four months in, I still enjoyed my job, though I was not sure I could call it a job because I had yet to be paid. According to my contract, I was to receive a check by the 15th of the month following the enrollment. I contacted Covered California. Apparently, they were not responsible for issuing payments. I emailed the California Department of Health Care Services. All I got was an automatic response alluding to a “system breakdown.”

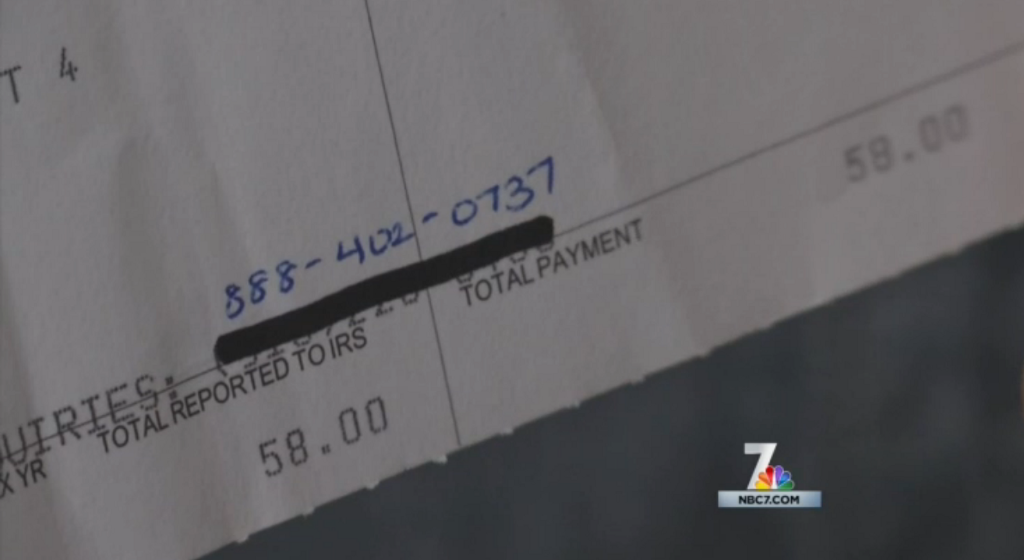

Nearly eight weeks later I received a check for $58—just a few thousand dollars short of what I was owed. I searched the stub for a contact person to dispute the amount and found a phone number that was blacked out with marker. Above it was an 888 number handwritten in blue ink. It’s rare that you see anything handwritten from a government agency. Maybe the person responsible for dealing with angry contractors got fed up and decided to write someone else’s number down. That would actually be a pretty funny prank if it didn’t involve my finances. I called; it was Covered California’s Enrollment Counselor helpline. The operator said they have no information about payments.

I bowed out the agreement with the library and stopped assisting most clients, except for those who seemed desperate and completely lost on how to obtain health insurance. By “desperate” I mean they’d leave messages like, “I’m trying to buy insurance and this goddamn Obama website won’t work and no one answers the goddamn phone.”

As a last ditch effort to get the money owed to me (or at least a response from the State of California), I emailed each of my local news stations. Not even two hours after sending the messages, a reporter from San Diego’s NBC affiliate was on his way to my house.

The reporter arrived and walked me through the questions. He was very pleasant, had a calming voice, and unlike many television personalities, a normal-size head. Showtime! I tensed up a bit. I didn’t know if I was to look at the reporter or stare into the camera while speaking. I remember thinking one rule is for TV and the other is for YouTube rants. I told my story and we were done within 15 minutes.

Covered California Lags on Paychecks: Contractor

I let all my friends know I had declared war against The State of California and NBC would be airing the details at 6 p.m. By the time the piece aired, Covered California had responded. They claimed to have mailed a second check, which did arrive a day after the interview. It, too, was a couple thousand dollars short. NBC asked other Covered California contractors if they had also not been paid. All were in the same boat, but none would go on the record, likely for fear of losing future business with the State of California.

After the NBC interview and my subsequent tweets to the director of the Department of Health Care Services, I received much of what I was owed — more than a year after signing the contract. I also got an email from Covered California marked “urgent.” It asked if I was interested in participating in the enrollment program next year. There was one catch: Contractors would have to agree to work without compensation.

Dewan Gibson blogs at dewangibson.com.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments