A Gemstone in the Rough

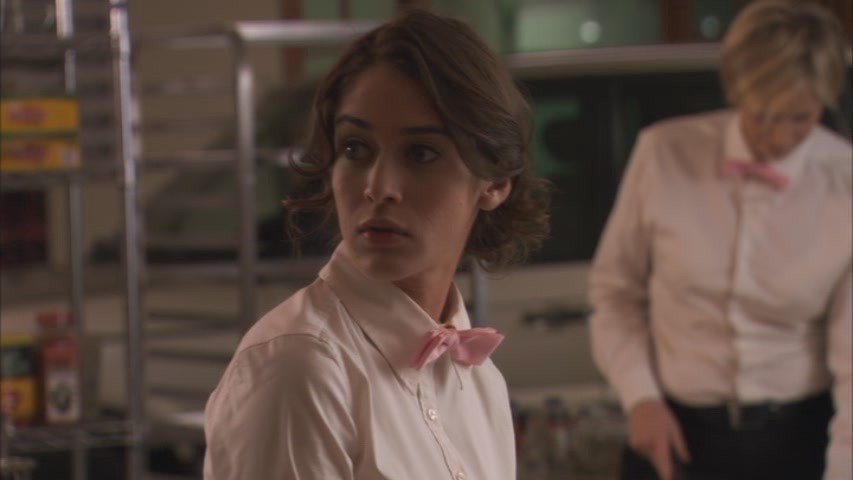

I’m sitting on an overturned plastic crate in the kitchen of Gemstone Catering, on the northside of Indianapolis. It’s Friday night and I’m wearing a size men’s extra-large white tuxedo shirt (It’s all they had the day I got hired), a clip on bow-tie and a tight black skirt. I’m balancing a plate of grilled chicken, salad, and my favorite — roasted potatoes — on my lap and sipping from a plastic cup of Coke.

The other servers and I are huddled in a circle around shelves full of industrial-size jars of mayonnaise and “creme”-filled Piroulene cookies. On the wall by the door is the machine where we clock in, and next to it is an old rag where we clip our name tags when we’re not working, for safe keeping.

The Mexican guys who work back here in the kitchen gave all the servers nicknames in Spanish. They call one server, Ryan, gusano, which is Spanish for worm. This because he’s tall and skinny. His little brother Carl is, naturally, gusanito (“little worm”). Ivan, who was born in Russia, is called rojo for red, Communist. My long blond hair qualifies me for the best nickname: Barbie. Hola Barbie, the guys say to me as I haul trays of dirty dishes into the kitchen. I feel beautiful, even if there is gravy smeared across my tuxedo shirt. Months ago I took to wearing a tight black skirt with black tights, in lieu of dress pants, like the real Barbie would have if she had my job.

“Electric Slide,” Ryan says, tossing a dollar onto the grease-stained floor.

“No. It is too early in the night for that. Next will be Shout,” Ivan responds in his matter-of-fact Russian accent. He places a crisp dollar bill on top of Ryan’s.

“Say My Name,” I call out. I’ve never heard this particular Destiny’s Child song played at a wedding I’ve catered, and I don’t have a dollar on me anyway, but it’s my favorite song. If it were to come on it would make my damn night.

Carl, whose dark brown hair falls in his eyes as he hunches over to eat, says, with a mouth full of chicken, “Redneck Wedding.” He pulls a wad of bills out of his pocket, fastened with a money clip, and throws two singles down onto the ground.

“Ohhh,” the other eight of us rumble in deep, guttural voices.

“Shit just got real,” Ivan says.

Through the walls we hear the DJ. “Who is having fun tonight!? Let’s hear it for Jason and Leslie! Who here is ready to boogie? Anyone who’s not on the dance floor needs to come on up for the next one. Grandma — I’m lookin’ at you! And you look so lovely tonight. Let’s hear it for Grandma, everyone!”

The beat drops. The song is fucking “Cotton Eye Joe.” That hyperactive sped-up remix version. Bullshit.

“I never would have guessed that in a million years,” I declare.

“Correct. Because you guess Say My Name with 100 percent accuracy,” says Ivan.

The money is scooped up and stuffed back into pockets. Forkfuls of food are shoved into mouths. There isn’t much time left before we need to get back out there and serve the wedding cake, which was cut before the dance break and yes — we are eating right now, too. They won’t miss a few pieces.

I was stoked to get my first job. I’d been wanting to work since before I could remember. In first grade I stayed after class once to ask my teacher for “more homework and less coloring.” I was desperate for something productive to do at home. I never had chores growing up, my mother being both a political libertarian (“Don’t tread on me”) and a passive personality, a combination that rendered her both morally opposed and emotionally unable to ask others to do things.

By the time older sister Katherine and I were adolescents all my friends had responsibilities. Leaves to rake, laundry to do, dishes to wash. Sometimes their chores would pile up so much come Saturday that they’d have to cancel plans to come over and jump on the trampoline in our back yard or go to the pool. It’s not like chores seemed fun, but it did seem to give their lives a certain purpose that mine appeared to lack. On weekend mornings, and every day during the summer, my routine was to sleep until noon and wake up in time to catch 1980’s-era Saturday Night Live reruns on Comedy Central. They had two hours of them, which occupied me until 2 p.m., when the looming expanse of the day would really get to me. Instead of facing it I’d usually just flip channels and watch Nickelodeon.

“Can we have chores?” I asked my mom, one night at dinner — salad and Kraft macaroni and cheese.

“Sure, what do you want to do?” mom replied, delicately picking at her greens. She always chopped it up into tiny pieces, smaller than bite-size.

“Maybe vacuum?” I suggested. That seemed sufficiently unpleasant.

“Sure, honey.”

“Oh! Can mine be feeding the squirrels?” Katherine said, her mouth full of macaroni and cheese.

“Sure, honey.”

“Awesome. I bet they eat salad,” she said, swiftly scooping the greens on her plate into her cupped hands and trotting outside, through the garage door.

My mother took a silent sip of her water, emitting not so much as a sigh.

Most of the weddings we catered at Gemstone were buffet-style, where a server’s job mostly consisted of refilling water glasses and clearing dirty dishes. Occasionally, though, there’d be plated dinners, more formal affairs where servers haul out a tray filled with nine dinners on heavy plates, covered with those metal covers I’d only seen at hotels or in like, that scene from Lady and the Tramp. You had to carry all nine at once to avoid “breaking your serve,” which means to serve some of the guests at your table, then disappear to the kitchen for the rest, creating an awkward social dynamic for the guests.

At about 110 pounds, hauling nine dinners on my shoulder was a bit of an ask, but I managed fine. Once I made it to the banquet hall I knew exactly what to do: Gemstone had a policy of serving “the oldest looking woman at the table first, and working clockwise from her.”

As I worked, I imagined the guests were envious of me for my youthful strength, my familiarity with something as fancy as the metal covers, and my belonging at Gemstone, whereas they were just visitors for the night.

Having work to do; it felt like it does when you crave vegetables for dinner after a day of too much snacking. My whole life, I realized, had been snacking. At the end of the night we had to stack all the chairs into these big towers so we could vacuum the whole 300-seat banquet hall. Some of the staff could go home, but I opted to stay late.

As the months went by I found myself more and more invested in the weddings. Best men and maids of honor gave toasts, which I got to listen to as I scanned the room for water glasses in need of refilling, my back straight like a soldier. Sometimes a single tear would trickle down my cheek as I listened to a particularly heartwarming speech.

One time a little old lady asked me if I wouldn’t mind getting her a piece from the edge of the wedding cake, where there was more frosting. When I returned with it I winked at her — something I don’t think I’d ever done in earnest before. She licked her lips and held out a soft, crinkled one dollar bill in her trembling hand. I took it and, because I had no pockets, retreated to the ice room and shoved it into my bra. At home that night it fell onto my bedroom floor as I undressed, like I imagined happened to strippers after their shifts. It was so wet from my sweat that it was difficult to unfold. I fucking earned this dollar, I thought.

At first only a few kids from my high school worked at Gemstone, but once word got out that you got free cake and made $9 an hour, it was on — minimum wage at the time was $5.15.

I got my friend Andy a job (for which I was supposed to receive a 25 cent raise I never saw. If any of my former supervisors are reading this and would like to rectify this wrong, I could use some extra scratch.) Then Andy, who was excitable and popular, especially among the theater crowd, got like 10 of our other friends jobs there.

Some Friday and Saturday nights the entire serving staff would be sourced from our high school, so we naturally began to feel like the parties were for us. Kind of like how little kids play make-believe games where they have jobs, except our playground was the most important day of other people’s lives.

One Saturday I stood opposite Andy in the lobby of Gemstone, balancing a tray of salads on my shoulder. We all had salads on our shoulders because we were participating in something called a “salad parade.”

We had to wait for a few extra moments because a grandparent had gone rogue, kicking off the toasts before dinner was served. “Kelsey is such a special girl. She’s truly one of a kind. So unique,” we heard through the walls.

The 12 servers stood in two neat rows, like the little French school girls in those Madeline books. At the front, Bryan, our steadfast manager, used his hands to demonstrate how we would march in even parallel lines to the front of the banquet center and then smoothly part ways, fanning out like synchronized swimmers. He checked his wristwatch and then held up one hand, fingers splayed out. “Five minutes,” he mouthed dramatically, so that his lips could be read even at the back of the line.

“I dare you to lick a cucumber slice,” Andy whispered to me.

I did it immediately and without thought, never breaking eye contact with him as my fat tongue coated the cucumber with my saliva. I dangled it a few inches above the salad plate, pinched seductively between my thumb and index finger, and then dropped it. He squealed with glee.

As the Buddhists teach, every perfect, beautiful thing descends into a shit storm eventually (I’m paraphrasing), and Gemstone Catering was no different. After about a year there it was clear that it was pretty damned hard to get fired from that place (unless, like Bryan, you were caught by the owners stealing Merlot by the case). The other servers and I took to dawdling, hiding out in the ice room stealing second and third pieces of cake. Or otherwise loitering on the sidelines of the banquet hall, playing “fuck, marry, kill” with the guests.

“OK, OK, I’d kill the tubby wino uncle, fuck the groomsman in the wheelchair, and marry that sad sister-in-law,” I said to Andy one night, leaning against the wall, letting my tables’ dishes pile up. One night I even broke my serve.

There was always coffee with the wedding cake — both regular and decaf. But when it got busy we, the teenage servers, collectively decided making both was too much of a bother and we just filled all the carafes, even the ones with the orange tops, with regular coffee. “Is that decaf?” Little old ladies would ask. “Sure is,” I’d smile back, and pour them a steaming cup-full.

One night Andy, sweaty and overwhelmed with four 12-top tables, rolled up his sleeve and dunked his forearm into a pitcher of iced tea before serving it. He looked at me and shook his head as he did it, clearly worn out, but with a cheeky glimmer in his eye.

After a year at Gemstone I had catered dozens of weddings, stood on the sidelines for dozens of people’s “special days.” It began to wear on me. I couldn’t help noticing that they all had the same food. (The “princess buffet,” which came with chicken breast and roasted potatoes, was the cheapest and far-and-away most popular option.) The DJs played the same tired, celebratory songs. After a few months I could scan my tables and within minutes spot who the entitled ones were — the ones who would ask me for extra cake with grins plastered across their faces.

Even the toasts began to blur together. “Jamey is so special.” “Paul is one crazy dude.” “Lainey is so kind and sweet.” And they were shockingly generic. If there was a specific story given, it almost always had to do with Spring Break.

There was never an original soul in the bunch. Except of course, for me.

And the love between the two? Eh. Given the national divorce rate, it was a safe bet at least half the weddings I worked would be nothing but bitter memories for the bride and groom within a few short years. My own wedding will be nothing like these, I told myself. I’d be out in nature or something, barefoot, or maybe I’d be some kind of Buddhist by then and could wear a costume. Or maybe I’d just fucking elope.

In a bizarre twist of cosmic retribution, our high school decided to hold its prom at Gemstone Catering the year Andy and I were juniors. We went together — despite the facts that he is gay and I had a boyfriend — I think because neither of us could bear the thought of attending something like that in earnest. We did the same thing at parties as we did at Gemstone, standing off to the side making fun of people, rooting around in kitchen cabinets for snacks that weren’t offered to us. I often neglected to change out of my sweaty, food-stained catering uniform if I went to a party after a shift. I claimed it was out of laziness but now I know it was just fear.

I sometimes wonder if catering attracts a specific kind of person, a kind of cultural voyeur, someone who takes an almost lascivious delight in watching other people make fools of themselves — by which I mean simply trying, at life.

At prom Andy and I stood on the sidelines most of the night, picking at the same food we ate every weekend and playing “fuck, marry, kill” with members of the student council — nice kids who worked hard to put on a nice event for everyone. My boyfriend went with a group of friends, including a red-haired girl he wound up dating shortly after he and I fizzled out. It made a fair amount sense, when I found out they were together. I thought back to a party I’d shown up to months before, dressed in my catering uniform. I’d seen him drawing a temporary tattoo with Sharpie marker on her shoulder, exposed by the cute tank top she was wearing.

Getting married is a more vulnerable thing than I think most people give it credit for. Yes, sure, you’re joining your life with someone else, which, I hear, is a thing that can provide a certain level of security and comfort. But you’re also giving up the ability to be 16 and stand on the sidelines in a tight skirt and sneer at other people for being cheesy or dumpy or normal.

It seems like to get married, to really go for it with someone else, you’ve got to turn away from the judgmental teenager inside you and start making decisions based instead on love. You have to be a little bit uncool. You have to let your soon-to-be mother-in-law make you a pair of ugly earrings in her crafting class and then wear them. You have to get the cheapest buffet because you’re on a budget for this thing and you have a lot of cousins. You’ve gotta let the DJ play that stupid song about “dancing like nobody’s watching.” And then you actually have to dance like nobody’s watching.

Somebody is definitely watching, though. Make no mistake about that.

The writer is based in Oakland, Calif.

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments