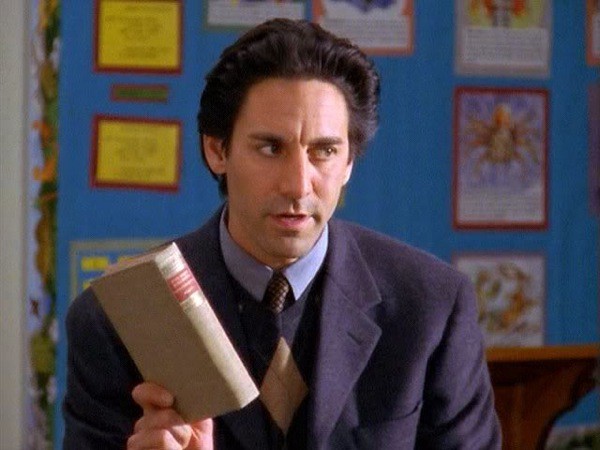

How Gilmore Girls Do Money: Max Medina

When Max Medina talks to his students, he tries to help them understand that a little failure — a few dips in the road, now and then–can be okay.

“You can’t make it through life without taking a few risks,” he says, knowing that the words sound both trite and overwrought simultaneously.

He used to give them more details. The time he had a well-paying job teaching at a private school in Connecticut. His decision, based partially on ambition but mostly on heartbreak, to take an adjunct position at Stanford. When he tells this story, he always leaves out the part where he moves back to Hartford for a year, because it seems too ludicrous to explain — he loved a woman, and he wanted more than anything else to know how their story would end. He had spent his whole life studying stories. He wanted this one to have an ending, but instead it had just stopped, as if a writer somewhere had grown tired of the narrative.

So he went back to Stanford. Diane could be part of his story. It would be a revision.

He gave up the lease on his cozy Hartford apartment and moved into a boxy unit on the corner from one of those new businesses that advertised “Checks Into Cash.” It was the kind of building that had ancient, grime-gray vertical blinds, and yet the landlord insisted they could not be removed. Max had come from a place flush with money and had assumed he would arrive in a similar situation — after all, it was Stanford, right? But he quickly learned that money did not work the same way in the Bay Area as it did in Hartford, Connecticut.

He told himself he would become a professor after one year. Then, after three years. It was impossible for him to imagine not achieving this goal, because Max Medina had, thus far, achieved every goal he set for himself (except one, but he counted that as a win because she had said yes). He worked hard. He paid attention. When someone said “send me a thousand daisies,” he called up every florist in town.

His CV was impeccable and yet he never got picked. He was still teaching the same night class they hired him to teach two years ago, the one that met twice a week and paid $3,000 for the semester, and adding other courses as they became available. One semester, his section of English Composition got canceled for reasons he didn’t quite understand. Max had a vision of himself showing up in the hallway, books in hand, ready to teach any student who was ready to learn, but that vision seemed a lot less realistic in the morning, and even though he had set his alarm early enough to allow himself to make it to his canceled class at the appointed time, he shut it off and went back to sleep.

Diane was gone by then because Diane was always just his metaphor, the idea he used to represent what he had wanted with Lorelai. He was very good about keeping Diane a metaphor, never a simile — he never thought “she is like Lorelai” or “we are as Lorelai and I could have been” — but she left anyway, the way the metaphor disappears when you turn the page, leaving you with the memory of its intended emotion. Max was always the kind of reader who gulped down paragraphs and pages, filtering the words through his brain to be rinsed and analyzed later and letting the emotions carry him through the story. He was also the kind of person who used the word “emotion” instead of “feeling.”

Max did not think about his finances in any specific sense; he could have defined sunk cost if you had asked him, but he could not have applied it to his own life. He gradually realized that he was not earning enough money, but he did not know what he needed to do to solve this problem. It seemed like his life had gotten worse since he had moved, and at first he thought it was heartbreak, and then he thought it was career disappointment, and then he wondered if it wasn’t also money.

When he explains to his students how he got a new job and moved himself out of a “bad situation,” he leaves out the part about how his parents funded the move. He focuses on the elements of the story that he thinks can be helpful: It is okay to fail. It is okay to make mistakes. Keep working hard, and you’ll succeed. He used to drop in a reference to his credit card debt until he understood that his students weren’t looking surprised because he had so much debt, but because he had access to so much credit.

So now he keeps it simple. “Every life has a few bumps in the road,” he says. “But you have to take those risks and go after what you want.”

Previously on “How Gilmore Girls Do Money:” Brian Fuller

Support The Billfold

The Billfold continues to exist thanks to support from our readers. Help us continue to do our work by making a monthly pledge on Patreon or a one-time-only contribution through PayPal.

Comments